First things first: I would like to wish Popsych.org a happy two-year anniversary. Here’s looking at many more. That’s enough celebration for now; back to the regularly scheduled events.

When it comes to reading and writing, academics are fairly busy people. Despite these constraints on time, some of us (especially the male sections) still make sure to take the extra time to examine the articles we’re reading to ascertain the gender of the authors so as to systematically avoid citing women, irrespective of the quality of their work. OK; maybe that sounds just a bit silly. Provided people like that actually exist in any appreciable sense of the word, their representation among academics must surely be a vast minority, else their presence would be well known. So what are we to make of the recently-reported finding that, among some political science journals, female academics tend to have their work cited less often than might be expected, given a host of variables (Maliniak, Power, & Walter, 2013)? Perhaps there might exist some covert bias against female authors, such that the people doing the citing aren’t even aware that they favor the work of men, relative to women. If the conclusions of the current paper are to be believed, this is precisely what we’re seeing (among other things). Sexism – even the unconscious kind – is a bit of a politically hot topic to handle so, naturally, I suggest we jump right into the debate with complete disregard for the potential consequences; you know, for the fun of it all.

I would like to begin the review of this paper by noting a rather interesting facet of the tone of the introduction: what it does and does not label as “problematic”. What is labeled as problematic is the fact that women do not appear to earning tenured positions in equal proportion to the number of women earning PhDs. Though they discuss this fact in the light of the political science field, I assume they intend their conclusion to span many fields. This is the well-known leaky pipeline issue about which much has been written. What is not labeled as problematic are the facts in the next two sentences: women make up 57% of the undergraduate population, 52% of the graduate population, and these percentages are only expected to rise in the future. Admittedly, not every gender gap needs to be discussed in every paper that mentions them and, indeed, this gap might not actually mean much to us. I just want to note that women outnumbering men on campus by 1.3-to-1 and growing is mentioned without so much as batting an eye. The focus of the paper is unmistakably on considering the troubles that women will face. Well, sort of; a more accurate way of putting it is that the focus is on the assumed troubles that women will face: difficulty getting cited. As we will see, this citation issue is far from a problem exclusive to women.

Onto the main finding of interest: in the field of international relations, over 3000 articles across 12 influential journals spanning about 3 decades were coded for various descriptors about the article and the authors. Articles that were authored by men only were cited about 5 additional times, on average, than articles authored by women only. Since the average number of citations for all articles was about 25 citations per paper, this difference of 5 citations is labeled as “quite a significant” one, and understandably so; citation count appears to be becoming a more important part of the job process in academia. Importantly, the gap persisted at statistically significant levels even after controlling for factors like the age of the publication, the topic of study, whether it came from an R1 school, the methodological and theoretical approach taken in the paper, and the author’s tenure status. Statistically, being a woman seemed to be bad for citation count.

The authors suggest that this gap might be due to a few factors, though they appear to concede that a majority of the gap remains unexplained. The first explanation on offer is that women might be citing themselves less than men tend to (which they were: men averaged 0.4 self-citations per paper and women 0.25). However, subtracting out self-citation count and the average number of additional citations self-citation was thought to add does not entirely remove the gap either. The other possibility that the authors float involves what are called “citation cartels”, where authors or journals agree to cite each other, formally or informally, in order to artificially inflate citation counts. While they have no evidence concerning the extent to which this occurs, nor whether it occurs across any gendered lines, they at least report that anecdotes suggest this practice exists. Would that factor help us explain the gender gap? No clue; there’s no evidence. In any case, from these findings, the authors conclude:

“A research article written by a woman and published in any of the top journals will still receive significantly fewer citations than if the same article had been written by a man” (p.29, emphasis mine).

I find the emphasized section rather interesting, as nothing that the authors researched would allow them to reach that conclusion. They were certainly not controlling for the quality of the papers themselves, nor their conclusions. It seems that because they controlled for a number of variables, the authors might have gotten a bit overconfident in assuming they had controlled for all or most of the relevant ones.

Like other gender gaps, however, this one may not be entirely what it seems. Means are only one measure of central tendency, and not always preferable for describing one’s sample. For instance, the mean income of 10 people might be a million dollars provided nine have none and one is rather wealthy. A similar example might concern the “average” number of mates your typical male elephant seal has; while some have large harems, others are left out entirely from the mating game. In other words, a skewed distribution can result in means that are not entirely reflective of what many might consider the “true” average of the population. Another possible measure of central tendency we might consider, then, is the median: the value that falls in the middle of all the observed values, which is a bit more robust against outliers. Doing just that, we see that the gender gap in citation count vanishes entirely: not only does it not favor the men anymore, but it slightly favors the women in 2 of the 3 decades considered (the median for men from the 80s, 90s, and 00s are 5, 14, and 13; for women, 6, 14, and 15, respectively). Further, in two of the decades considered, mix-gendered articles appear to be favored by about 2-to-1 over papers with a single gender of author (medians equal 10, 22, and 16, respectively). Overall, the mean citation count looks to be about two-to-three times as high as the median, and the standard deviations of the citation count are huge. For instance, in the 1980s, articles authored by men averaged 17.6 citations per paper (substantially larger than the median of 5), and the SD of that count was 51.63. Yikes. Why is this rather interesting facet of the data not considered in much, if any, depth by the authors? I have no idea.

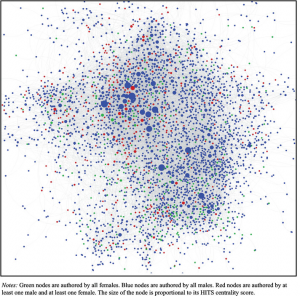

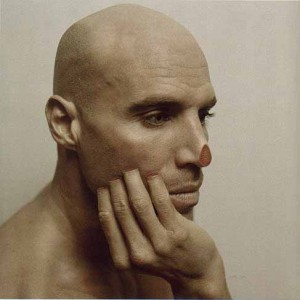

Now this is not to say that the mean or the median is necessarily the “correct” measure to consider here, but the fact that they return such different values ought to give us some pause for consideration. Mean values that are over twice as large as the median values with huge standard deviations suggests that we’re dealing with a rather skewed distribution, where some papers garner citation counts which are remarkably higher than others (a trend I wrote about recently with respect to cultural products). Now the authors do state that their results remain even if any outliers above 3 standard deviations are removed from the analysis, but I think that upper limit probably fails to fully capture what’s going on here. This handy graphical representation of citation count provided in the paper can help shed some light on the issue.

What we see is not a terribly-noticeable trend for men to be cited more than women in general, as much as we see a trend for the papers with the largest citation counts to come disproportionately from men. The work of most of the men, like most of the women, would seem to linger in relative obscurity. Even the mixed-sex papers fail to reach the heights that male-only papers tend to. In other words, the prototypical paper by women doesn’t seem to differ too much from the prototypical male paper; the “rockstar” papers (of which I’d estimate there are about 20 to 30 of in that picture), however, do differ substantially along gendered lines. Gendered lines are not the only way in which they might differ, however. A more accurate way of phrasing the questionable conclusion I quoted earlier would be to say “A research article written by anyone other than the initial author, if published in any of the top journals, might still receive significantly fewer citation even if it was the same article”. Cultural products can be capricious in their popularity, and even minor variations in initial conditions can set the stage for later popularity, or lack thereof.

This would naturally raise the question as to precisely why the papers with the largest impact come from men, relative to women. Unfortunately, I don’t have a good answer for that question. There is undoubtedly some cultural inertia to account for; were I to publish the same book as Steven Pinker in a parallel set of universes, I doubt mine would sell nearly as many copies (Steven has over 94,000 twitter followers, whereas I have more fingers and toes than fans). There is also a good deal of noise to consider: an article might not end up being popular because it was printed in the wrong place at the wrong time, rather than because of its quality. On the subject on quality, however, some papers are better than others, by whatever metric we’re using to determine such things (typically, that standard is “I know it when I wish I had thought of it first”). Though none of these factors lend themselves to analysis in any straightforward way, the important point is to not jump to overstated conclusions about sexism being the culprit, or to suggest that reviewers “…monitor the ratio of male to female citations in articles they publish” so as to point it out to the authors in the hopes of “remedying” any potential “imbalances”. One might also, I suppose, have reviewers suggest that authors make a conscious effort to cite articles with lower citation counts more broadly, so as to ensure a greater parity among citation counts in all articles. I don’t know why that state of affairs would be preferable, but one could suggest it.

References: Maliniak, D., Powers, R., & Walter, B. (2013). The gender citation gap in international relations. International Organization DOI: 10.1017/S0020818313000209