My last couple of posts have focused primarily on the topic of group differences and on understanding how they might come to exist. Some of the most commonly-advanced explanations for these differences concern discrimination – explicit or implicit – that serves to keep otherwise interested and qualified people out of arenas they would like to compete in. For example, few men might want to be nurses because male nurses aren’t considered for positions even if they’re qualified because of a social stigma against men in that area. If that was the explanation for these group differences, it would represent a wealth of untapped social value achievable by reducing or removing those discriminatory boundaries. On the other hand, if discrimination is not the cause of those differences, a lot of time and energy could be invested into chasing down a boogeyman without yielding much in the way of value for anyone.

Unfortunately, as we saw last time (and other times), research seeking to test these explanations can be designed or interpreted in ways that make them resilient to falsification. If the hypothesized effect attributable to discrimination is observed, it is counted as evidence consistent with the explanation; when the effect isn’t observed, however, it is not counted as evidence against the proposal. They are sure the discrimination is there; they just didn’t dig deep enough to find it. This practice can be maintained effectively in many domains because of the fuzzy nature of performance within them. That is, it’s not always clear which person would make a better manager or professor when it comes time to make a hiring decision or assess performance, so different rates of hiring or promotions cannot be clearly related to different behavior.

And if the quality of your work can’t be assessed, it also means you can never be said to fail at your job

One way of working that fuzziness out of the equation is to turn towards domains where more objective measures of performance can be obtained. While it might be difficult to say for certain that one person would make a superior manager to another – especially when they are closely matched in skills – it is quite a lot easier to see if they can complete a task with objective performance criteria, such as winning in a video game or performing pull-ups. In realms of objective performance, it doesn’t matter if people like you or not; your abilities are being tested against reality. Accordingly, domains with more objective performance criteria make for appealing research tools when it comes to assessing and understanding group differences.

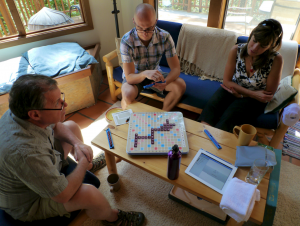

On that note, Moxley, Ericsson, & Tuffiash (2017) report some interesting information concerning the board game SCRABBLE. For the handful of you who might not know what SCRABBLE is, it’s a game where each player randomly selects a number of tiles with letters on them, then uses those tiles to spell words: the larger the word or the harder the letters are to utilize, the more points the player receives. The player with the most points after the tiles have been used up wins. As it turns out, men tend to be over-represented in the upper tiers of SCRABBLE performance. Within the highest-performing competitive SCRABBLE divisions, 86% of the players are male, while only 31% of the players in the lowest-performing divisions are. This patterns holds even though most of the competitive SCRABBLE players are women. Indeed, when regular people are asked about whether they would expect more male or female SCRABBLE champions, the intuition seems to be that women should be more common (despite, for context, all 10 of the last world champions having been male).

How is that sex difference in performance to be explained? In this instance, discrimination looks to be an odd explanation: competitive SCRABBLE tournaments do not present clear barriers to entry and women appear to be at least as interested – if not more so – in SCRABBLE than men are, as inferred from participation rates. Moreover, people even seem to expect women would do better than men in that field, so an explanation along the lines of stereotype threat doesn’t work well either. According to the research of Moxley, Ericsson, & Tuffiash (2017), the explanation for most of that sex difference in performance does, in fact, relate to varying male and female interests, but perhaps not those directed at playing SCRABBLE itself. While I won’t discuss every part of the studies they undertook, I wanted to highlight some general points of this research because of how well it can highlight the difficulty and nuance in understanding sex differences and their relation to performance within a given field.

Even this vicious field of battle

The general methodology employed by the researchers involved surveying participants at National SCRABBLE competitions in 2004 and 2008 about their overall level of practice each year, both in terms of time spent studying alone and practicing seriously with others. These responses were then examined in the context of the player’s competitive SCRABBLE rating. The first study turned up several noteworthy relationships. As expected, women tended to have lower ratings than men (d = -0.74). However, it was also found that different types of SCRABBLE practice had varying impacts on player ratings. In this case, studying vocabulary had a negative impact on performance, while time spent analyzing past games and doing anagrams had a positive impact. This means that just asking people about how much they practiced SCRABBLE is not enough of a fine-tuned question for good predictive accuracy concerning performance. In this case, the practice questions asked about were unable to account for the entirety of the gender difference in performance, but they did reduce it somewhat.

This led the researchers to ask more detailed questions about SCRABBLE players’ practice in their second study. As before, women tended to have lower ratings than men (d = -0.69), but once the more refined questions about practice and experience were accounted for, there was no longer a direct effect of gender on rating. This would suggest that the performance advantage men had in SCRABBLE can be largely attributed to their spending more time engaged in solitary practice that benefits performance, while women tended to spend more time playing SCRABBLE with others; a behavior which did not yield comparable performance benefits.

The final step in this analysis was to figure out why men and women spent different amounts of time engaged in the types of practice they did. To do so, the players’ responses about how relevant, enjoyable, and effortful various types of practice felt were assessed. In order, the players felt tournament experience was the most important for improving their skills, then playing SCRABBLE itself, followed last by other types of word games. On that front, perceptions weren’t quite accurate. A similar pattern emerged in terms of which activities were rated as most enjoyable. However, there was a sex difference in that women rated playing SCRABBLE outside of tournaments as more enjoyable than men, and men rated SCRABBLE-specific practice (like anagrams) as more enjoyable than women.

Taken together, men tended to find the most-effective practice methods more enjoyable than women, and so engaged in them more. This differential involvement in effective practice in turn explained the sex difference in player rankings. Nothing too shocking, but reality often isn’t.

Published in the journal of, “I’m sorry; did you say something?”

What we see in this research is an appreciable sex difference in performance resulting from varying male and female interests, but those interests themselves are not necessarily the most obvious targets for investigation. If you were to just ask men and women whether they were interested in SCRABBLE, you might find that women had a higher average interest. If you were to just ask about how much time they spent practicing, you might not observe a sex difference capable of explaining the differences in performance. It wouldn’t be until you asked specifically about their interests in particular types of practice and understood how those related to eventual performance that you end up with a better picture of that performance gap. In this case, it seems to be the case that the sex difference is largely the product of men being more interested in specific types of practice that are ultimately more productive when it comes to improving performance. The corollary point to that is that if you were trying to reduce the male-female performance gap in SCRABBLE, if your explanation for that gap was that women are being discriminated against and so sought to reduce discrimination in the field, you’d probably do nothing to help even out the scores (though you might achieve some social maligning).

Thankfully this kind of analysis can be reasonably undertaken in a realm where performance can be objectively assessed. If you were to think about trying this same analysis with respect to, say, the relative distribution of men and women in STEM fields, you’re in for a much rockier experience where it’s not clear how certain interests relate to ultimate performance.

References: Moxley, J., Ericsson, A., & Tuffiash, M. (2017). Gender differences in SCRABBLE performance and associated engagement in purposeful practice activities. Psychological Research, DOI 10.1007/s00426-017-0905-3