Sometime ago I was invited to give a radio interview regarding a post I had written: The Politics of Fear. Having never been exposed to this kind of a format before, I found myself having to try and make some adjustments to my planned presentation on the fly, as it quickly became apparent that the interviewer was looking more for quick and overly-simplified answers, rather than anything with real depth (and who can blame him? It’s not like many people are tuning into the radio with the expectation of receiving anything resembling a college education). At one point I was posed with a question along the lines of, “how people can avoid letting their political biases get the better of them,” which was a matter I was not adequately prepared to answer. In the interests of compromise and giving the poor host at least something he could work with (rather than the real answer: “I have no idea; give me a day or two and I’ll see what I can find”), I came up with a plausible sounding guess: try to avoid social isolation of your viewpoints. In other words, don’t remove people from your friend groups or social media just because you disagree with they they say, and actively seek out opposing views. I also suggested that one attempt to expand their legitimate interests in the welfare of other groups in order to help take their views more seriously. Without real and constant challenges to your views, you can end up stuck in a political and social echo chamber, and that will often hinder your ability to see the world as it actually is.

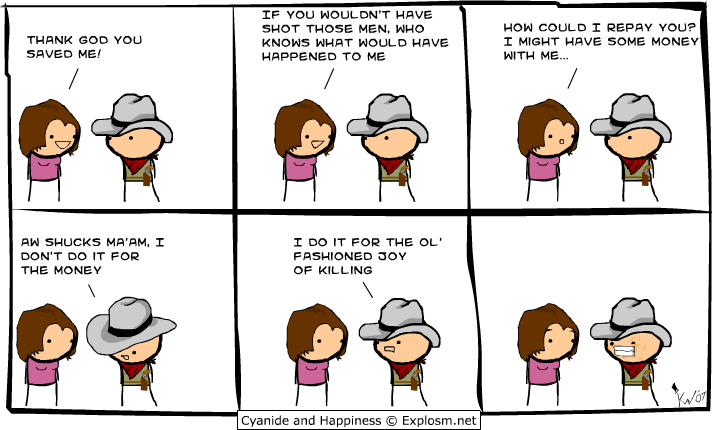

“Can you believe those nuts who think flooding poses real risks?”

As luck would have it, a new paper (Almaatouq et al, 2016) fell into my lap recently that – at least in some, indirect extent – helps speak to the quality of the answer I had provided at the time (spoiler: as expected, my answer was pointing in the right direction but was incomplete and overly-simplified). The first part of the paper examines the shape of friendships themselves: specifically whether they tend to be reciprocal or more unrequited in one direction or the other. The second part leverages those factors to try and explain what kinds of friendships can be useful for generating behavioral change (in this case, getting people to be more active). Put simply, if you want to change someone’s behavior (or, presumably, their opinions) does it matter if (a) you think they’re your friend, but they disagree, (b) they think you’re their friend, but you disagree, (c) whether you both agree, and (d) how close you are as friends?

The first set of data reports on some general friendship demographics. Surveys were provided to 84 students in a single undergraduate course that asked to indicate, from 0-5, whether they considered the other students to be strangers (0), friends (3), or one of their best friends (5). The students were also asked to predict how each other student in the class would rate them. In other words, you would be asked, “How close do you rate your relationship with X?” and “How close does X rate their relationship to you?” A friendship was considered mutual if both parties rated each other as at least a 3 or greater. There was indeed a positive correlation between the two ratings (r = .36), as we should expect: if I rate you highly as a friend, there should be a good chance you also rate me highly. However, that reality did diverge significantly from what the students predicted. If a student has nominated someone as a friend, their prediction as to how that person would rate them showed substantially more correspondence (r = .95). Expressed in percentages, if I nominated someone as a friend, I would expect them to nominate me back about 95% of the time. In reality, however, they would only do so about 53% of the time.

The matter of why this inaccuracy exists is curious. Almaatouq et al, (2016) put forward two explanations, one of which is terrible and one of which is quite plausible. The former explanation (which isn’t really examined in any detail, and so might just have been tossed in) is that people are inaccurate at predicting these friendships because non-reciprocal friendships “challenge one’s self-image.” This is a bad explanation because (a) the idea of a “self” isn’t consistent with what we know about how the brain works, (b) maintaining a positive attitude about oneself does nothing adaptive per se, and (c) it would need to posit a mind that is troubled by unflattering information and so chooses to ignore it, rather than the simpler solution of a mind that is simply not troubled by such information in the first place. The second, plausible explanation is that some of these ratings of friendships actually reflect some degree of aspiration, rather than just current reality: because people want friendships with particular others, they behave in ways likely to help them obtain such friendships (such as by nominating their relationship as mutual). If these ratings are partially reflective of one’s intent to develop them over time, that could explain some inaccuracy.

Though not discussed in the paper, it is also possible that perceivers aren’t entirely accurate because people intentionally conceal friendship information from others. Imagine, for instance, what consequences might arise for someone who finally works up the nerve to go tell their co-workers how they really feel about them. By disguising the strength of our friendships publicly, we can leverage social advantages from that information asymmetry. Better to have people think you like them than know you don’t in many cases.

”Of course I wasn’t thinking of murdering you to finally get some quiet”

With this understanding of how and why relationships can be reciprocal or asymmetrical, we can turn to the matter of how they might influence our behavior and, in turn, how satisfactory my answer was. The authors utilized a data set from the Friends and Family study, which had asked a group of 108 people to rate each other as friends on a 0-7 scale, as well as collected information about their physical activity level (passively, via a device in their smartphones). In this study, participants could earn money by becoming more physically active. In the control condition, participants could only see their own information; in the two social conditions (that were combined for analysis) they could see both their own activity levels and those of two other peers: in one case, participants earned a reward based only on their own behavior, and in the other the reward was based on the behavior of their peers (it was intended to be a peer-pressure condition). The relationship variables and conditions were entered into a regression to predict the participant’s change in physical activity.

In general, having information about the activity levels of peers tended to increase the activity of the participants, but the nature of those relationships mattered. Information about the behavior of peers in reciprocal friendships had the largest effect (b = 0.44) on affecting change. In other words, if you got information about people you liked who also liked you, this appeared to be most relevant. The other type of relationship that significantly predicted change was one in which someone else valued you as a friend, even if you might not value them as much (b = 0.31). By contrast, if you valued someone else who did not share that feeling, information about their activity didn’t seem to predict behavioral changes well (b = 0.15) and, moreover, the strength of friendships seemed to be rather besides the point (b = -0.04), which was rather interesting. Whether people were friends seemed to matter more than the depth of that friendship.

So what do these results tell us about my initial answer regarding how to avoid perceptual biases in the social world? This requires a bit of speculation, but I was heading in the right direction: if you want to affect some kind of behavioral change (in this case, reducing one’s biases rather than increasing physical activity), information from or about other people is likely a tool that could be effectively leveraged for that end. Learning that other people hold different views than your own could cause you to think about the matter a little more deeply, or in a new light. However, it’s often not going to be good enough to simply see these dissenting opinions in your everyday life if you want to end up with a meaningful change. If you don’t value someone else as an associate, they don’t value you, or neither of you value the other, then their opinions are going to be less effective at changing yours than they otherwise might be, relative to when you both value each other.

At least if mutual friendship doesn’t work, there’s always violence

The real tricky part of that equation is how one goes about generating those bonds with others who hold divergent opinions. It’s certainly not the easiest thing in the world to form meaningful, mutual friendships with people who disagree (sometimes vehemently) with your outlooks on life. Moreover, achieving an outcome like “reducing cognitive biases” isn’t even always an adaptive thing to do; if it were, it would be remarkable that those biases existed in the first place. When people are biased in their assessment of research evidence, for instance, they’re usually biased because something is on the line, as far as they’re concerned. It does an academic who has built his career on his personal theory no favors to proudly proclaim, “I’ve spent the last 20 years of my life being wrong and achieving nothing of lasting importance, but thanks for the salary and grant funding.” As such, the motivation to make meaningful friendships with those who disagree with them is probably a bit on the negative side (unless their hope is that through this friendship they can persuade the other person to adopt their views, rather than vice versa because – surely – the bias lies with other people; not me). As such, I’m not hopeful that my recommendation would play out well in practice, but at least it sounds plausible enough in theory.

References: Almaatouq, A., Radaelli, L., Pentland, A., & Shmueli, E. (2016). Are you your friends’ friends? Poor perception of friendship ties limits the ability to promote behavioral change. PLOS One, 11, e0151588. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151588