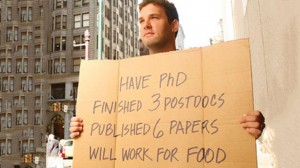

One of the latest political soundbites I have seen circling my social media is a comment by Jeb Bush regarding psychology majors and the value their degrees afford them in the job market. This is a rather interesting topic for me for a few reasons, chief among which is, obviously, I’m a psychology major currently engaged in application season. As one of the psych-majoring, job-seeking types, I’ve discussed job prospects with many friends and colleagues from time to time. The general impression I’ve been given up until this week is that – at least for psychology majors with graduate degrees looking to get into academia – the job market is not as bright as one might hope. The typical job search can involve months or years of posting dozens or hundreds of applications to various schools, with many graduates reduced to taking underpaid positions as adjuncts, making barely enough to pay their bills. By contrast, I’ve had friends in other programs tell me about how their undergraduate degree has people metaphorically lining up to give them a job; jobs that would likely pay them a starting salary that could be the same or more than I could demand with a PhD in psychology, even in private industry. Considered along those dimensions, a degree envy can easily arise.

Slanderous rumor incoming in 3…2…

Job envy aside, let’s consider the quote from Jeb:

“Universities ought to have skin in the game. When a student shows up, they ought to say ‘Hey, that psych major deal, that philosophy major thing, that’s great, it’s important to have liberal arts … but realize, you’re going to be working a Chick-fil-A…The number one degree program for students in this country … is psychology. I don’t think we should dictate majors. But I just don’t think people are getting jobs as psych majors. We have huge shortages of electricians, welders, plumbers, information technologists, teachers.”

Others have already weighed in on this comment, noting that, well, it’s not exactly true: psychology is only the second most common major, and most of the people with psychology BAs don’t end up working in fast food. The median starting salary for someone with a BA in psychology is about $38,000 a year, which rises to about $62,000 after 10 years if this data set I’ve been looking at is accurate. So that’s hardly fast food wages, even if it might be underwhelming to some.

However, there are some slightly more charitable ways of interpreting Jeb’s comment (provided one feels charitable towards him, which many do not): perhaps one might consider instead how psychology majors do on the job market relative to other majors. After all, just having a college degree tends to help people find good jobs, relative to having no degree at all. So how do psychology majors do in that data set I just mentioned? Of the 319 majors listed and ranked by mid-career income, psychology can be found in three locations (starting and mid-career salaries, respectively):

- (138) Industrial Psych – 45/74k

- (231) Psychology – 38/62k

- (292) Psychology & Sociology – 35/55k

So, despite its popularity as a major, the salary prospects of psychology majors tend to fall below the mid-point of the expected pay scale. Indeed, the median salary of psychology majors is quite similar to theater (38/59k), creative writing (38/63k), or art history majors (40/64k). Not to belittle any of those majors either, but it is possible that much of the salary benefits from holding these degrees comes from holding a college degree in general, rather than those ones in particular. Nevertheless, these salaries are also fairly comparable to electricians, plumbers, and welders, or at least the estimates Google returns to me; information technologists seem to have better prospects, though (55/84K).

In general, then, the comment by Jeb seems off-base when taken literally: most of the fields he mentions tend to do about as well as psychology majors, and most psychology majors are not making minimum wage. With a charitable interpretation, there is something worth thinking about, though: psychology majors don’t seem to do particularly well when compared with other majors. Indeed, about 25 of the listed majors have median starting salaries at 60k or above; the median of psychology majors after 10 years of working. Now, yes; there is more to a career and an education than what financial payoff one eventually reaps from it (once one pays off the costs of a college degree), but there’s also room to think about how much value the degree you are receiving adds to your life and the lives of others, relative to your options. In fact, I think that concern has a lot to do with why Jeb mentioned the careers he does: it’s not hard to see how the skills a plumber or an electrician learns during their training are applied in their eventual career; the path between a psychology education and a profitable career that provides others with a needed service is not quite as easy to imagine.

It’s down at the bottom; I promise

This brings us to a rather old piece of research regarding psychology majors. Lunneborg & Wilson (1985) sought to answer an interesting question: would psychology majors major in psychology again, if they had to the option to do it all over? Their sample was made up of about 800 psychology majors who had graduated between 1978 and 1982. In addition to the “would you major in psychology again” question, participants were also asked to provide their impressions of the importance of their college experience in general, those of the psychology courses they took in particular, and their satisfaction with the skills they felt they gained through their psychology education on a scale from 0 to 4. Of the 750 participants who responded to the question regarding whether they would major in psychology again, 522 (69%) indicated that they would (conversely, 31% would not). While some other specific numbers are not mentioned (unfortunately), the authors report that those who graduated more recently were more likely to indicate a willingness to major in psychology again, relative to those who had been graduates for a longer period of time, perhaps suggesting that some realities of the job market have yet to set in.

More precise numbers are provided, however, to the questions concerning the perceived value of the psychology major. Psychology degrees were rated as most relevant to personal growth (M = 2.38) and liberal arts education (M = 2.23), but less so for graduate preparation in psychology (M = 1.78), graduate preparation outside of psychology (M = 1.61), or career preparation in general (M = 1.49). While people seemed to find psychology interesting, they were more ambivalent about whether they were walking away from their education with career-relevant skills. Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that those who continued on with their education (at the MA level or above) were more satisfied with their education than those who stopped at the BA, as it is at these higher levels that skill sets begin to be explored and applied more fully. Indeed, the authors also report that those who said they were working in a field related to psychology or in their desired field of work were more likely to indicate they would major in psychology again. When things worked out, people seemed inclined to repeat their choices; when their results were less fortunate, people were more inclined to make different choices.

As I mentioned before, making money is not the only reason people seek out certain degrees.This is backed up by the fact that a full 43% of respondents who rated their career preparation from a psychology major as a 0 said they would major in the field again (as compared with 100% who rated career preparation as a 3). People find learning about how people think interesting – I certainly know I do – and so they are often naturally drawn to such courses. It’s a bit more engaging for most to hear about the decisions people make than it is to learn about, say, abstract calculus That psychology is interesting to people is a good consolation for its students, considering that psychology majors are among the most likely to be unemployed, relative to other college majors, and the earning premium of their degrees is also among the lowest.

“…But not at Chik-fil-A; I have standards, after all”

Returning to Jeb’s comment one last time, we can see some truth to what he said if we consider the heart of the matter, rather than the specifics: psychology majors do not have outstanding job prospects relative to other college majors – whether in terms of expected income or employment more generally – and psychology majors also report career preparation as being one of the least relevant things about their education, at least at the BA level. It would seem that many psychology majors are getting jobs not necessarily because of their psychology major, but perhaps because they had a major. Some degree is better than no degree in the job market; a fact that many non-degree holders are painfully aware of. Despite their career prospects, psychology remains the second most popular major in the US, attesting to people’s interest in hearing about the subject. On the other hand, if we consider the specifics, Jeb’s comment is wrong: psychology majors are not working fast food jobs, their income is about on the same level of the other careers he lists, and psychology is the second most – not first – popular major. Which parts of all this information sound most relevant likely depends on your position relative to them: most psychology majors do not enjoy having their field of study denigrated, as the reaction to Jeb’s comments showed; his political opponents likely want to have this comment do the most amount of harm to Jeb as possible (and a heavy degree of overlap likely exists between these two groups). Nevertheless, there are some realities of people’s degrees that ought to not get lost in the defense against comments like these.

References: Lunneborg, P. & Wilson, V. (1985). Would you major in psychology again? Teaching of Psychology, 1, 17-20.