As I mentioned in my last post, I’m a big fan of games. For the last couple of years, the game which has held the majority of my attention has been a digital card game. In this game, people have the ability to design decks with different strategies, and the success of your strategy will depend on the strategy of your own opponent; you can think of it as a more complicated rock-paper-scissors component. The players in this game are often interested in understanding how well certain strategies match up against others, so, for the sake of figuring that out, some have taken it upon themselves to collect data from the players to answer those questions. You don’t need to know much about the game to understand the example I’m about to discuss, but let’s just consider two decks: deck A and deck B. Those collecting the data managed to aggregate the outcome of approximately 2,200 matches between the two and found that, overall, deck A was favored to win the match 55% of the time. This should be some pretty convincing data when it comes to getting a sense for how things generally worked out, given the large sample size.

Only about 466 more games to Legend with that win rate

However, this data will only be as useful to us as our ability to correctly interpret it. A 55% success rate captures the average performance, but there is at least one well-known outlier player within the game in that match. This individual manages to consistently perform at a substantially higher level than average, achieving wins in that same match up around 70-90% of the time across large sample sizes. What are we to make of that particular data point? How should it affect our interpretation of the match? One possible interpretation is that his massively positive success rate is simply due to variance and, given enough games, the win rate of that individual should be expected to drop. It hasn’t yet, as far as I know. Another possible explanation is that this player is particularly good, relative to his opponents, and that factor of general skill explains the difference. In much the same way, an absolutely weak 15-year-old might look pretty strong if you put him in a boxing match against a young child. However, the way the game is set up you can be assured that he will be matched against people of (relatively) equal skill, and that difference shouldn’t account for such a large disparity.

A third interpretation – one which I find more appealing, given my deep experience with the game – is that skill matters, but in a different way. Specifically, deck A is more difficult to play correctly than deck B; it’s just easier to make meaningful mistakes and you usually have a greater number of options available to you. As such, if you give two players of average skill decks A and B, you might observe the 55% win rate initially cited. On the other hand, if you give an expert player both decks (one who understands that match as well as possible), you might see something closer to the 80% figure. Expertise matters for one deck a lot more than the other. Depending on how you want to interpret the data, then, you’ll end up with two conclusions that are quite different: either the match is almost even, or the match is heavily lopsided. I bring this example up because it can tell us something very important about outliers: data points that are, in some way, quite unusual. Sometimes these data points can be flukes and worth disregarding if we want to learn about how relationships in the world tend to work; other times, however, these outliers can provide us valuable and novel insights that re-contextualize the way we look at vast swaths of other data points. It all hinges on the matter of why that outlier is one.

This point bears on some reactions I received to the last post I wrote about a fairly-new study which finds no relationship between violent content in video games and subsequent measures of aggression once you account for the difficulty of a game (or, perhaps more precisely, the ability of a game to impede people’s feelings of competence). Glossing the results into a single sentence, the general finding is that the frustration induced by a game, but not violent content per se, is a predictor of short-term changes in aggression (the gaming community tends to agree with such a conclusion, for whatever that’s worth). In conducting this research, the authors hoped to address what they perceived to be a shortcoming in the literature: many previous studies had participants play either violent or non-violent games, but they usually achieved this method by having them play entirely different games. This means that while violent content did vary between conditions, so too could have a number of other factors, and the presence of those other factors poses some confounds in interpreting the data. Since more than violence varied, any subsequent changes in aggression are not necessarily attributable to violent content per se.

Other causes include being out $60 for a new controller

The study I wrote about, which found no effect of violence, stands in contrast to a somewhat older meta-analysis of the relationship between violent games and aggression. A meta-analysis – for those not in the know – is when a larger number of studies are examined jointly to better estimate the size of some effect. As any individual study only provides us with a snapshot of information and could be unreliable, it should be expected that a greater number of studies will provide us with a more accurate view of the world, just like running 50 participants through an experiment should give us a better sense than asking a single person or two. The results of some of those meta-analyses seem to settle on a pretty small relationship between violent video games and aggression/violence (approximately r = .15 to .20 for non-serious aggression, and about r = .04 for serious aggression depending on who you ask and what you look at; Anderson et a, 2010; Ferguson & Kilburn, 2010; Bushman et al, 2010), but there have been concerns raised about publication bias and the use of non-standardized measures of aggression.

Further, were there no publication bias to worry about, that does not mean the topic itself is being researched by people without biases, which can affect how data gets analyzed, research gets conducted, measures get created and interpreted, and so on. If r = .2 is about the best one can do with those degrees of freedom (in other words, assuming the people conducting such research are looking for the largest possible effect and develop their research accordingly), then it seems unlikely that this kind of effect is worth worrying too much about. As Ferguson & Kilburn (2010) note, youth violent crime rates have been steadily decreasing as the sale of violent games have been increasing (r = -.95; as well, the quality of that violence has improved over time; not just the quantity. Look at the violence in Doom over the years to get a better sense for that improvement). Now it’s true enough that the relationship between youth violent crime and violent video game sales is by no means a great examination of the relationship in question, but I do not doubt that if the relationship ran in the opposite direction (especially if were as large), many of the same people who disregard it as unimportant would never leave it alone.

Again, however, we run into that issue where our data is only as good as our ability to interpret it. We want to know why the meta-analysis turned up a positive (albeit small) relationship whereas the single paper did not turn up such a relationship, despite multiple chances to find it. Perhaps the paper I wrote about was simply a statistical fluke; for whatever reason, the samples recruited for those studies didn’t end up showing the effect of violent content, but the effect is still real in general (perhaps it’s just too small to be reliably detected). That seems to be the conclusion some responses I received contained. In fact, I had one commenter who cited the results of three different studies suggesting there was a casual link between violent content and aggression. However, when I dug up those studies and looked at the methods section, what I found was that, as I mentioned before, all of them had participants play entirely different games between violent and non-violent conditions. This messes with your ability to interpret the data only in light of violent content, because you are varying more than just violence (even if unintentionally). On the other hand, the paper I mentioned in my last post had participants playing the same game between conditions, just with content (like difficulty or violence levels) manipulated. As far as I can tell, then, the methods of the paper I discussed last week were superior, since they were able to control more, apparently-important factors.

This returns us to the card game example I raised initially: when people play a particular deck incorrectly, they find it is slightly favored to win; when someone plays it correctly they find it is massively favored. To turn that point to this analysis, when you conduct research that lacks the proper controls, you might find an effect; when you add those controls in, the effect vanishes. If one data point is an outlier because it reflects research done better than the others, you want to pay more attention to it. Now I’m not about to go digging through over 130 studies for the sake of a single post – I do have other things on my plate – but I wanted to make this point clear: if a meta-analysis contains 130 papers which all reflect the same basic confound, then looking at them together makes me no more convinced of their conclusion than looking at any of them alone (and given that the specific studies that were cited in response to my post all did contain that confound, I’ve seen no evidence inconsistent with that proposal yet). Repeating the same mistake a lot does not make it cease to be a mistake, and it doesn’t impress me concerning the weight of the evidence. The evidence acquired through weak methodologies is light indeed.

Research: Making the same mistakes over and over again for similar results

So, in summation, you want to really get to know your data and understand why it looks the way it does before you draw much in the way of meaningful conclusions from it. A single outlier can potentially tell you more about what you want to know than lots of worse data points (in fact, it might not even be the case that poorly-interpreted data is recognized as such until contrary evidence rears its head). This isn’t always the case, but to write off any particular data point because it doesn’t conform to the rest of the average pattern – or to assume its value is equal to that of other points – isn’t always right either. Meeting your data, methods, and your measures is quite important for getting a sense for how to interpret it all.

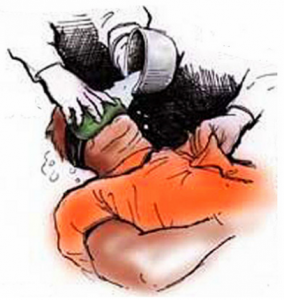

For instance, it has been proposed that – sure – the relationship between violent game content and aggression is small at best (there seems to be some heated debate over whether it’s closer to r = .1 or .2) but it could still be important because lots of small effects can add up over time into a big one. In other words, maybe you ought to be really wary of that guy who has been playing a violent game for an hour each night for the last three years. He could be about to snap at the slightest hint of a threat and harm you…at least to the extent that you’re afraid he might suggest you listen to loud noises or eat slightly more of something spicy; two methods used to assess “physical” aggression in this literature due to ethical limitations (despite the fact that, “Naturally, children (and adults) wishing to be aggressive do not chase after their targets with jars of hot sauce or headphones with which to administer bursts of white noise.” That small, r = .2 correlation I referenced before concerns behavior like that in a lab setting where experimental demand characteristics are almost surely present, suggesting the effect on aggressive behavior in naturalistic settings is likely overstated.)

Then again, in terms of meaningful impact, perhaps all those small effects weren’t really mounting to much. Indeed, the longitudinal research in this area seems to find the smallest effects (Anderson et al, 2010). To put that into what I think is a good example, imagine going to the gym. Listening to music helps many people work out, and the choice of music is relevant there. The type of music I would listen to when at the gym is not always the same kind I would listen to if I wanted to relax, or dance, or set a romantic mood. In fact, the music I listen to at the gym might even make me somewhat more aggressive in a manner of speaking (e.g., for an hour, aggressive thoughts might be more accessible to me while I listen than if I had no music, but that don’t actually lead to any meaningful changes in my violent behavior while at the gym or once I leave that anyone can observe). In that case, repeated exposure to this kind of aggressive music would not really make me any more aggressive in my day-to-day life than you’d expect overtime.

Thankfully, these warnings managed to save people from dangerous music

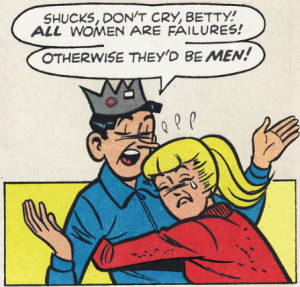

That’s not to say that media has no impact on people whatsoever: I fully suspect that people watching a horror movie probably feel more afraid than they otherwise would; I also suspect someone who just watched an action movie might have some violent fantasies in their head. However, I also suspect such changes are rather specific and of a short duration: watching that horror movie might increase someone’s fear of being eaten by zombies or ability to be startled, but not their fear of dying from the flu or their probability of being scared next week; that action movie might make someone think about attacking an enemy military base in the jungle with two machine guns, but it probably won’t increase their interest in kicking a puppy for fun, or lead to them fighting with their boss next month. These effects might push some feelings around in the very short term, but they’re not going to have lasting and general effects. As I said at the beginning of last week, things like violence are strategic acts, and it doesn’t seem plausible that violent media (like, say, comic books) will make them any more advisable.

References: Anderson, C. et al. (2010). Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and western counties: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 151-173.

Bushman, B., Rothstein, H., & Anderson, C. (2010). Much ado about something: Violent video game effects and school of red herring: Reply to Ferguson & KIlburn (2010). Psychological Bulletin, 136, 182-187.

Elson, M. & Ferguson, C. (2013). Twenty-five years of research on violence in digital games and aggression: Empirical evidence, perspectives, and a debate gone astray. European Psychologist, 19, 33-46.

Ferguson, C. & Kilburn, J. (2010). Much ado about nothing: The misestimation and overinterpretation of violent video game effects in eastern and western nations: Comment on Anderson et al (2010). Psychological Bulletin, 136, 174-178.