Atheists are good friends because they keep it real

There’s an interesting finding rolling around about what kinds of people Americans would vote for as a president. When asked:

“If your party nominated a generally well-qualified person for president who happened to be [blank], would you vote for that that person?”

Answers varied a bit depending on the blank: 96% of Americans would vote for a Black president (while only 4% would not); 95% would vote for a woman. Characteristics like that don’t really dissuade people, at least in the abstract. Other groups don’t fare as well: only 68% of people said they would vote for a gay/lesbian candidate, and 58% a Muslim. But bottoming out the list? Atheists. A mere 54% of people said they would vote for an atheist. This is also a finding that changes a bit – but not all that much – between political affiliations. At the low point, 48% of Republicans would vote for an atheist, while at its peak, 58% of Democrats would. An appreciable difference, but not night and day (larger differences exist for Mormon, gay/lesbian and Muslim candidates, coming in at 18%, 26%, and 22%, respectively).

At the outset – and this is a point that will become important later – it is worth noting that the answers to these questions might not tell you how people would feel about any particular atheist, woman, Muslim, etc. They are not asking whether people would vote for a specific atheist; they are asking about voting for an atheist in the abstract sense of the word, so they are relying on stereotype information. It is also worth noting that people have become much more tolerant over time: in 1958, only 18% said they would vote for an atheist, so getting up to over half (and up to 70% in the younger generation) is good progress. Of course, only 38% said they would vote for a black person during that same year which, as we just saw, has changed dramatically to near 100% by 2012. Atheists haven’t made similar gains, in terms of degree.

This is a very interesting finding that begs for a proper explanation. What is it about atheists that puts people off so much? While I can’t provide a comprehensive or definitive answer at the moment, there is some research I wanted to discuss today that helps shed some light on the issue.

Spoilers…

The basic premise of this research is effectively that – to some (perhaps large) degree – religion per se isn’t what people are necessarily concerned about when they’re providing their answers to questions like our voting one. Instead, what concerns people are other, more-relevant factors that religiosity just so happens to correlate with. So people are really concerned with trait X in a candidate, but are using religiosity as a means of indirectly assessing the presence of trait X. In case that all sounds a bit too abstract, let’s make it concrete and think about the trait Moon, Krems, and Cohen (2018) examined: trust.

When considering who you’d like to support politically or interact with socially, trust is an important factor. If you know you can trust someone, this increases the types of cooperation you can safely engage in with them. When you cannot trust someone, for instance, interactions with them need to be relatively immediate for the sake of safety: I give you the money now and I get my product now. If they aren’t trustworthy, you should be less inclined to give them money now for the promise of your product in a day, week, month, year, or beyond, as they might just take your money and run. By contrast, someone who is trustworthy can offer cooperation over the longer term. The same logic applies to a leader. If you cannot trust a leader to work in your interests, why follow them and offer your support?

As it turns out, religious people are perceived to be more trustworthy than the nonreligious. Why might this be the case? One ostensibly obvious explanation that might jump out at you is that religious people tend to believe in deities that punish people for misbehavior. If someone believes they will be punished for breaking a promise, they should be less likely to break that promise, all else being equal. This is one explanation for the trust finding, then, but there’s an issue: it’s quite easy to just say you believe in a punishing deity when you actually do not. Since that signal is so cheap to produce, it wouldn’t be trustworthy.

This is where religion in particular might help, as membership in a religious group often involves some degree of costly investment: visits to houses of worship, following rituals that are a real pain to complete, and any other similar behavior. Those who are unwilling to endure those immediate costs for group membership demonstrate that they’re just talk. Their commitment doesn’t run deep enough for them to be willing to suffer for them. When behavior is no longer cheap, you can believe what people are telling you. Now this might make religious people look more trustworthy because it demonstrates they’re more groupish and – by extension – more cooperative, but this groupishness is a double-edged sword: those who are inclined towards their group are usually less inclined towards others. This might mean that religious people are more trustworthy to their in-group, but not necessarily their outgroup.

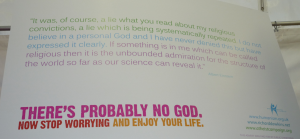

“Who’s up next to demonstrate their trustworthiness?”

There are other explanations, though. The one the present paper favors is the possibility that religious people tend to follow slower life history strategies. This means possessing traits like sexual restrictiveness (they’re relatively monogamous, or at least less promiscuous), greater investment in family, and generally more future-looking than they are living in the present. This would be what makes them look more cooperative than the non-religious. Fast life history strategies are effectively the opposite: they view life as short and unpredictable and so take benefits today instead of saving for tomorrow, and invest more in mating effort than parental effort. Looking at religious individuals as slow-life strategists fits well with previous research suggesting that religious attitudes correlate better with sexual morality than they do cooperative morality, and that religions might act as support for long-term, monogamous, high-fertility mating strategies.

As with many stereotypes, those about religious individuals possessing these slow-life-history traits to a greater degree seems to be fairly accurate. So, when people are asked to judge an individual and are given no more information about them than their religion, they may tend to default to using those stereotypes to assess other traits of interest, like trust. This should also predict that when people know more about a particular individual’s life history strategy – be it fast or slow – religion per se should cease to be used as a predictor. After all, why bother to use religion to assess someone’s life history strategy when you can just assess that strategy directly? Religion stops adding anything at that point, and so information about it should be largely discarded.

As it turns out, this is basically what the research uncovered. In the first experiment people (N = 336) were asked whether they perceived targets (dating profiles of religious or non-religious individuals) as possessing traits like aggression, impulsivity, education, whether they thought they came from a rough neighborhood, and whether they trusted the person. As expected, people perceived the religious targets as being less aggressive, impulsive, more educated, more committed in sexual relationships, and – accordingly – trusted them more. These perceptions held even for the non-religious raters on average, who appeared to trust religious people more than those who shared their lack of belief. Experiment three basically replicated these same results, but also found that the effects were partially independent of the specific religion in question. That is, whether the target being judged was Christian or Muslim, they were still both trusted more than the non-religious targets (even if Christians were nominally trusted more than Muslims, likely due to the majority religion of the country in which the research took place).

Mileage may vary on the basis of local religious majorities

Experiment two is where the real interesting finding emerged. The procedure was generally the same as before, but now the dating profiles contained better individuating information about the person’s life history strategy. In this case, the targets described themselves either as looking for “someone special, settling downing, and starting a family,” or one who, “doesn’t see themselves setting down anytime soon, as they enjoy playing the field” (paraphrased slightly). When rating these profiles with better information about the person (beyond simply their religious behavior/belief), the effect of commitment strategy on trust was much larger (ηp2 = .197) than the effect of religion per se (ηp2 = .008).

The authors also tried to understand which variables predicted this relationship between reproductive strategy and trust. Their first model used “belief in god” as a mediator and did indeed find a small, but significant relationship running from reproductive strategy predicting belief in god which in turn predicted trust. However, when other life history traits were included as mediator variables (like impulsivity, opportunistic behavior, education, and hopeful ecology – which means what kind of neighborhood one comes from, effectively), the belief in god mediator was no longer significant while three of the life history variables were.

In short, this would suggest that belief in god itself is not the thing doing much of the pulling when it comes to understanding why people trust religious people more. Instead, people are using religion as something of a proxy for someone’s likely reproductive strategy and, accordingly, life history traits. As such, when people have information directly bearing on the traits they’re interested in assessing, they largely stop using their stereotypes about religion in general and instead rely on information about the person (which is completely consistent with previous research on how people use stereotype information: when no other information is available, stereotypes are used, but as more individuating information is available, people rely on that more and their stereotypes less).

References: Moon, J., Krems, J., & Cohen, A. (2018). Religious people are trusted because they are viewed as slow life-history strategists. Psychological Science, DOI: 10.1177/0956797617753606