There are moments from my education that have stuck with me over time. One such moment involved a professor teaching his class about what might be considered a “classic” paper in social psychology. I happened to have been aware of this particular paper for two reasons: first, it was a consistent feature in many of my previous psychology classes and, second, because the news had broke recently that when people tried to replicate the effect they had failed to find it. Now a failure to replicate does not necessarily mean that the findings of the original study were a fluke or the result of experimental demand characteristics (I happen to think they are), but that’s not even why this moment in my education stood out to me. What made this moment stand out is that when I emailed the professor after class to let him know the finding had recently failed to replicate, his response was that he was aware of the failure. This seemed somewhat peculiar to me; if he knew the study had failed to replicate, why didn’t he at least mention that to his students? It seems like rather important information for the students to have and, frankly, a responsibility of the person teaching the material, since ignorance was no excuse in this case.

“It was true when I was an undergrad, and that’s how it will remain in my class”

Stories of failures to replicate have been making the rounds again lately, thanks to a massive effort on the part of hundreds of researchers to try and replicate 100 published effects in three psychology journals. These researchers worked with the original authors, used the original materials, were open about their methods, pre-registered their analyses, and archived all their data. Of these 100 published papers, 97 of them reported their effect as being statistically significant, with the other 3 being right on the borderline of significance and interpreted as being a positive effect. Now there is debate over the value of using these kinds of statistical tests in the first place, but, when the researchers tried to replicate these 100 effects using the statistically significant criterion, only 37 even managed to cross the barrier (given that 89 were expected to replicate if the effects were real, 37 is falling quite short of that goal).

There are other ways to assess these replications, though. One method is to examine the differences in effect size. The 100 original papers reported an average effect size of about 0.4; the attempted replications saw this average drop to about 0.2. A full 82% of the original papers showed a stronger effect size than the attempted replications, While there was a positive correlation (about r = 0.5) between the two – the stronger the original effect, the stronger the replication effect tended to be – this still represents an important decrease in the estimated size of these effects, in addition to their statistical existence. Another method of measuring replication success – unreliable as it might be – is to get the researcher’s subjective opinions about whether the results seemed to replicate. On that front, the researchers felt about 39 of the original 100 findings replicated; quite in line with the above statistical data. Finally, perhaps worth noting, social psychology research tended replicate less often than cognitive research (25% and 50%, respectively), and interaction effects replicated less often than simple effects (22% and 47%, respectively).

The scope of the problem may be a bit larger than that, however. In this case, the 100 papers upon which replication efforts were undertaken were drawn from three of the top journals in psychology. Assuming a positive correlation exists between journal quality (as measured by impact factor) and the quality of research they publish, the failures to replicate here should, in fact, be an underestimate of the actual replication issue across the whole field. If over 60% of papers failing to replicate is putting the problem a bit mildly, there’s likely quite a bit to be concerned about when it comes to psychology research. Noting the problem is only one step in the process towards correction, though; if we want to do something about it, we’re going to need to know why it happens.

So come join in my armchair for some speculation

There are some problems people already suspect as being important culprits. First, there are biases in the publication process itself. One such problem is that journals seem to overwhelmingly prefer to report positive findings; very few people want to read about a bad experiment which didn’t work out well. A related problem, however, is that many journals like to publish surprising, or counter-intuitive findings. Again, this can be attributed to the idea that people don’t want to read about things they already believe are true: most people perceive the sky as blue and research confirming this intuition won’t make many waves. However, I would also reckon that counter-intuitive findings are surprising to people precisely because they are also more likely to be inaccurate descriptions of reality. If that’s the case, than a preference on the part of journal editors for publishing positive, counter-intuitive findings might set them up to publish a lot of statistical flukes.

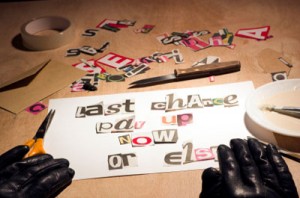

There’s also the problem I’ve written about before, concerning what are known as “research degrees of freedom“; more colloquially, we might consider this a form of data manipulation. In cases like these, researchers are looking for positive effects, so they test 20 people in each group and peak at the data. If they find an effect, they stop and publish it; if they don’t, they add a few more people and peak again, continuing until they find what they want or run out of resources. They might also split the data up into various groups and permutations until they find a set of data that “works”, so to speak (break it down by male/female, or high/medium/low, etc). While they are not directly faking the data (though some researchers do that as well), they are being rather selective about how they analyze it. Such methods inflate the possibility of finding of effect through statistical brute force, even if the effect doesn’t actually exist.

This problem is not unique to psychology, either. A recent paper by Kaplan & Irvin (2015) examined research from 1970-2012 that was looking at the effectiveness of various drugs and dietary supplements for preventing or treating cardiovascular disease. There were 55 trials that met the author’s inclusion criteria. What’s important to note about these trials is that, prior to the year 2000, none of the papers were pre-registered with respect to what variables they were interested in assessing; after 2000, every such study was pre-registered. Registering this research is important, as it doesn’t allow the researchers to then conduct a selective set of analyses on their data. Sure enough, prior to 2000, 57% of trials reported statistically-significant effects; after 2000, that number dropped to 8%. Indeed, about half the papers published after 2000 did report some statistically significant effects, but only for variables other than the primary outcomes they registered. While this finding is not necessarily a failure to replicate per se, it certainly does make one wonder about the reliability of those non-registered findings.

And some of those trials were studying death as an outcome, so that’s not good…

There is one last problem I would like to mention; one I’ve been beating the drum for for the past several years. Assuming that pre-registering research in psychology would help weed out false positives (it likely would), we would still be faced with the problem that most psychology research would not find anything of value, if the above data are any indication. In the most polite way possible, this would lead me to ask a question along the lines of, “why are so many psychology researchers bad at generating good hypotheses?” A pre-registered bad idea does not suddenly make it a good one, even if it makes data analysis a little less problematic. This leads me to my suggestion for improving research in psychology: the requirement of actual theory for guiding research. In psychology, most theories are not theories, but rather restatements of a finding. However, when psychologists begin to take an evolutionary approach to their work, the quality of research (in my obviously-biased mind) tends to improve dramatically. Even if the theory is wrong, making it explicit allows problems to be more easily discussed, discovered, and corrected (provided, of course, that one understands how to evaluate and test such theories, which many people unfortunately do not). Without guiding/foundational theories, the only thing you’re left with when it comes to generating hypotheses are the existing data and your intuitions which, again, don’t seem to be good guides for conducting quality research.

References: Kaplan, R. & Irvin, V. (2015). Likelihood of null effects of large NHLBI clinical trials has increased over time. PLoS One, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.013238