Selfies used to be a bit more hardcore

If you were asked to think about what makes a great leader, there are a number of traits you might call to mind, though what traits those happen to be might depend on what leader you call to mind: Hitler, Gandhi, Bush, Martin Luther King Jr, Mao, Clinton, or Lincoln were all leaders, but seemingly much different people. What kind of thing could possibly tie all these different people and personalities together under the same conceptual umbrella? While their characters may have all differed, there is one thing all these people shared in common and it’s what makes anyone anywhere a leader: they all had followers.

Humans are a social species and, as such, our social alliances have long been key to our ability to survive and reproduce over our evolutionary history (largely based around some variant of the point that two people are better at beating up one person than a single individual is; an idea that works with cooperation as well). While having people around who were willing to do what you wanted have clearly been important, this perspective on what makes a leader – possessing followers – turns the question of what makes a great leader on its head: rather than asking about what characteristics make one a great leader, you might instead ask what characteristics make one an attractive social target for followers. After all, while it might be good to have social support, you need to understand why people are willing to support others in the first place to fully understand the matter. If it was all cost to being a follower (supporting a leader at your own expense), then no one would be a follower. There must be benefits that flow to followers to make following appealing. Nailing down what those benefits are and why they are appealing should better help us understand how to become a leader, or how to fall from a position of leadership.

With this perspective in mind, our colorful cast of historical leaders suddenly becomes more understandable: they vary in character, personality, intelligence, and political views, but they must have all offered their followers something valuable; it’s just that whatever that something(s) was, it need not be the same something. Defense from rivals, economic benefits, friendship, the withholding of punishment: all of these are valuable resources that followers might receive from an alliance with a leader, even from the position of a subordinate. That something may also vary from time to time: the leader who got his start offering economic benefits might later transition into one who also provides defense from rivals; the leader who is followed out of fear of the costs they can inflict on you may later become a leader who offers you economic benefits. And so on.

“Come for the violence; stay for the money”

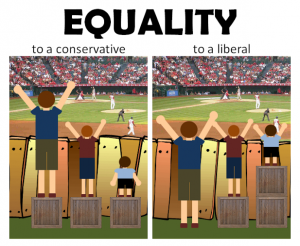

The corollary point is that features which fail to make one appealing to followers are unlikely to be the ones that define great leaders. For example – and of relevance to the current research on offer – gender per se is unlikely to define great leaders because being a man or a woman does not necessarily offer much to many followers. Traits associated with them might – like how those who are physically strong can help you fight against rivals better than one who is not, all else being equal – but not the gender itself. To the extent that one gender tends to end up in positions of leadership it is likely because they tend to possess higher levels of those desirable traits (or at least reside predominantly on the upper end of the population distribution of them). Possessing these favorable traits that allow leaders to do useful things is only one part of the equation, however: they must also appear willing to use those traits to provide benefits to their follows. If a leader possesses considerable social resources, they do you little good if said leader couldn’t be any less interested in granting you access to them.

This analysis also provides another context point for understanding the leader/follower dynamic: it ought to be context specific, at least to some extent. Followers who are looking for financial security might look for different leaders than those who are seeking protection from outside aggression; those facing personal social difficulties might defer to different leaders still. The match between the talents offer by a leader and the needs of the followers should help determine how appealing some leaders are. Even traits that might seem universally positive on their face – like a large social network – might not be positives to the extent it affects a potential follower’s perception of their likelihood of receiving benefits. For example, leaders with relatively full social rosters might appear less appealing to some followers if that follower is seeking a lot of a leader’s time; since too much of it is already spoken for, the follower might look elsewhere for a more personal leader. This can create ecological leadership niches that can be filled by different people at different times for different contexts.

With all that in mind, there are at least some generalizations we can make about what followers might find appealing in a leader in an, “all else being equal…” sense: those with more social support with be selected as leaders more often, as such resources are more capable of resolving disputes in your favor; those with greater physical strength or intelligence might be better leaders for similar reasons. Conversely, one might follow such leaders because of the costs failing to follow would incur, but the logic holds all the same. As such, once these and other important factors are accounted for, you should expect irrelevant factors – like sex – to fall out of the equation. Even if many leaders tend to be men, it’s not their maleness per se that makes them appealing leaders, but rather these valued and useful traits.

Very male, but maybe not CEO material

This is a hypothesis effectively tested in a recent paper by von Rueden et al (in press). The authors examined the distribution of leadership in a small-scale foraging/farming society in the Amazon, the Tsimane. Within this culture – as others – men tend to exercise the greater degree of political leadership, relative to women, as measured by domains including speaking more during social meetings, coordinating group efforts, and resolving disputes. The leadership status of members within this group were assessed by ratings of other group members. All adults within the community (male n = 80; female n = 72) were photographed, and these photos were then then given to 6 of the men and women in sets of 19. The raters were asked to place the photos in order in terms of which person whose voice tended to carry the most weight during debates, and then in terms of who managed the most community projects. These ratings were then summed up (from 1 to 19, depending on their position in the rankings, with 19 being the highest in terms of leadership) to figure out who tended to hold the largest positions of leadership.

As mentioned, men tended to reside in positions of greater leadership both in terms of debates and management (approximate mean male scores = 37; mean female scores = 22), and both men and women agreed on these ratings. A similar pattern was observed in terms of who tended to mediate conflicts within the community: 6 females were named in resolving such conflicts, compared with 17 males. Further, the males who were named as conflict mediators tended to be higher in leadership scores, relative to non-mediating males, while this pattern didn’t hold for the females.

So why were men in positions of leadership in greater percentages than females? A regression analysis was carried out using sex, height, weight, upper body strength, education, and number of cooperative partners predicting leadership scores. In this equation, sex (and height) no longer predicted leadership score, while all the other factors were significant predictors. In other words, it wasn’t that men were preferred as leaders per se, but rather that people with more upper body strength, education, and cooperative partners were favored, whether male or female. These traits were still favored in leaders despite leaders not being particularly likely to use force or violence in their position. Instead, it seems that traits like physical strength were favored because they could potentially be leveraged, if push came to shove.

“A vote for Jeff is a vote for building your community. Literally”

As one might expect, what makes followers want to follow a leader wasn’t their sex, but rather what skills the leader could bring to bear in resolving issues and settling disputes. While the current research is far from a comprehensive examination of all the factors that might tap leadership at different times and contexts, it represents a sound approach to understanding the problem of why followers select particular leaders. By thinking about what benefits followers tended to reap from leaders over evolutionary history can help inform our search for – and understanding of – the proximate mechanisms through which leaders end up attracting them.

References: von Rueden, C., Alami, S., Kaplan, H., & Gurven, M. (In Press). Sex differences in political leadership in an egalitarian society. Evolution & Human Behavior, doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.03.005