Several years back I wrote a post about the Dunning-Kruger effect. At the time I was still getting my metaphorical sea legs for writing and, as a result, I don’t think the post turned out as well as it could have. In the interests of holding myself to a higher standard, today I decided to revisit the topic both in the interests of improving upon the original post and generating a future reference for me (and hopefully you) when discussing it with others. This is something of a time-saver for me because people talk about the effect frequently despite, ironically, not really understanding it too deeply.

First things first, what is the Dunning-Kruger effect? As you’ll find summarized just about everywhere, it refers to the idea that people who are below-average performers in some domains – like logical reasoning or humor – will tend to judge their performance as being above average. In other words, people are inaccurate at judging how well their skills stack up to their peers or, in some cases, to some objective standard. Moreover, this effect gets larger the more unskilled one happens to be. Not only are the worst performers worse at the task then others, but they’re also worse at understanding they’re bad at the task. This effect was said to obtain because people need to know what good performance is before they can accurately assess their own. So, because below-average performers don’t understand how to perform a task correctly, they also lack the skills to judge their performance accurately, relative to others.

Now available at Ben & Jerry’s: Two Scoops of Failure

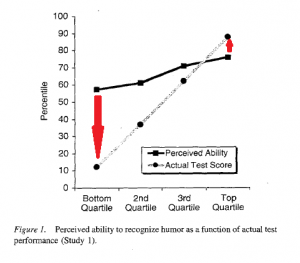

As mentioned in my initial post (and by Kruger & Dunning themselves), this type of effect shouldn’t extend to domains where production and judging skills can be uncoupled. Just because you can’t hit a note to save your life on karaoke night, that doesn’t mean you will be unable to figure out which other singers are bad. This effect should also be primarily limited to domains in which the feedback you receive isn’t objective or standards for performance are clear. If you’re asked to re-assemble a car engine, for instance, unskilled people will quickly realize they cannot do this unassisted. That said, to highlight the reason why the original explanation for this finding doesn’t quite work – not even for the domains that were studied in the original paper – I wanted to examine a rather important graph of the effect from Kruger & Dunning (1999) with respect to their humor study:

My crudely-added red arrows demonstrate the issue. On the left-hand side, we see what people refer to as the Dunning-Kruger effect: those who were the worst performers in the humor realm were also the most inaccurate in judging their own performance, compared to others. They were unskilled and unaware of it. However, the right-hand side betrays the real issue that caught my eye: the best performers were also inaccurate. The pattern you should expect, according to the original explanation, is that the higher one’s performance, the more accurately they estimate their relative standings, but what we see is that the best performers aren’t quite as accurate as those who are only modestly above average. At this point, some of you might be thinking that this point I’m raising is basically a non-issue because the best performers were still more accurate than the worst performers, and the right-hand inaccuracy I’m highlighting isn’t appreciable. Let me try to persuade you otherwise.

Assume for a moment that people were just guessing as to how they performed, relative to others. Because having a good sense of humor is a socially-desirable skill, people all tend to rate themselves “modestly above-average” in the domain to try and persuade others they actually are funny (and because, in that moment, there are no consequences to being wrong). Despite these just being guesses, those who actually are modestly above-average will appear to be more accurate in their self-assessment than those who are in the bottom half of the population; that accuracy just doesn’t have anything to do with their true level of insight into their abilities (referred to as their meta-cognitive skills). Likewise, those who are more than modestly above average (i.e. are underestimating their skills) will be less accurate as well; there will just be fewer of them than those who overestimated their abilities.

Considering the findings of Kruger & Dunning (1999) on the whole, the above scenario I just outlined doesn’t reflect reality perfectly. There was a positive correlation between people’s performance and their rating of their relative standing (r = .39), but, for the most part, people’s judgments of their own ability (the black line) appear relatively uniform. Then again, if you consider their results in studies two and three of that same paper (logical reasoning and grammar), the correlations between performance and judgments of performance relative to others drop to a low of r = .05 ranging up to a peak of r = .19, which was statistically significant. People’s judgments of their relative performance were almost flat across several such tasks. To the extent these meta-cognitive judgments of performance use actual performance as an input for determining relative standings, it’s clearly not the major factor for either low or high performers.

They all shop at the same cognitive store

Indeed, actual performance shouldn’t be expected to be the primary input for these meta-cognitive systems (the ones that generate relative judgments of performance) for two reasons. The first of these is the original performance explanation posited by Kruger & Dunning (1999): if the system generating the performance doesn’t have access to the “correct” answer, then it would seem particularly strange that another system – the meta-cognitive one – would have access to the correct answer, but only use it to judge performance, rather than to help generate it.

To put that in a quick memory example, say you were experiencing a tip-of-the-tongue state, where you are sure you know the right answer to a question, but you can’t quite recall it. In this instance, we have a long-term memory system generating performance (trying to recall an answer) and a meta-cognitive system generating confidence judgments (the tip-of-the-tongue state). If the meta-cognitive system had access to the correct answer, it should just share it with the long-term memory system, rather than using the correct answer to tell the other system to keep looking for the correct answer. The latter path is clearly inefficient and redundant. Instead, the meta-cognitive system should use some cues other than direct access to information in generating its judgments.

The second reason actual performance (relative to others) wouldn’t be an input for these meta-cognitive systems is that people don’t have reliable and accurate access to population-level data. If you’re asking people how funny they are relative to everyone else, they might have some sense for it (how funny are you, relative to some particular people you know), but they certainly don’t have access to how funny everyone is because they don’t know everyone; they don’t even know most people. If you don’t have the relevant information, then it should go without saying that you cannot use it to help inform your responses.

Better start meeting more people to do better in the next experiment

So if these meta-cognitive systems are using inputs other than accurate information in generating their judgments about how we stack up to others, what would those inputs be? One possible input would be task difficulty, not in the sense of how hard the task objectively is for a person to complete, but rather in terms of how difficult a task feels. This means that factors like how quickly an answer can be called to mind likely play a role in these judgments, even if the answer itself is wrong. If judging the humor value of a joke feels easy, people might be inclined to say they are above average in that domain, even if they aren’t.

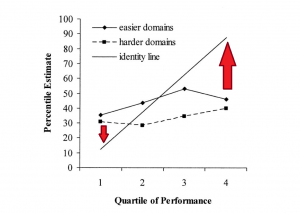

This yields an important prediction: if you provide people with tasks that feel difficult, you should see them largely begin to guess they are below-average in that domain. If everyone is effectively guessing that they are below average (regardless of their actual performance), this means that those who perform the best will be the most inaccurate in judging their relative ability. In tasks that feel easy, people might be unskilled and unaware; for those that feel hard, people might be skilled but still unaware.

This is precisely what Burson, Larrick, & Klayman (2006) tested, across three studies. While I won’t go into details about the specifics of all their studies (this is already getting long), I will recreate a graph from one of their three studies that captures their overall pattern of results pretty well:

As we can see, when the domains being tested became harder, it was now the case that the worst performers were more accurate in estimating their percentile rank than the best ones. On tasks of moderate difficulty, the best and worst performers were equally calibrated. However, it doesn’t seem that this accuracy is primarily due to their real insights into their performance; it just so happened to be the case that their guesses landed closer to the truth. When people think, “this task is hard,” they all seem to estimate their performance as being modestly below average; when the task feels easy instead, they all seem to estimate their performance as being modestly above average. The extent to which that matches reality is largely due to chance, relative to true insight.

Worth noting is that when you ask people to make different kinds of judgments, there is (or at least can be) a modest average advantage for top performers, relative to bottom ones. Specifically, when you ask people to judge their absolute performance (i.e., how many of these questions did you get right?) and compare that to their actual performance, the best performers sometimes had a better grasp on that estimate than the worst ones, but the size of that advantage varied depending on the nature of the task and wasn’t entirely consistent. Averaged across the studies reported by Burson et al (2006), top-half performers displayed a better correlation between their perceived and actual absolute performance (r = .45), relative to bottom performers (r = .05). The corresponding correlations for actual and relative percentiles were in the same direction, but lower (rs = .23 and .03, respectively). While there might be some truth to the idea that the best performers are more sensitive to their relative rank, the bulk of the miscalibration seems to be driven by other factors.

Driving still feels easy, so I’m still above-average at it

These judgments of one’s relative standing compared to others appear rather difficult for people to get accurate. As they should, really; for the most part we lack access to the relevant information/feedback and there are possible social-desirability issues to contend with, coupled with a lack on consequences for being wrong. This is basically a perfect storm for inaccuracy. Perhaps worth noting is that the correlation between one’s relative performance and their actual performance was pretty close for one domain in particular in Burson et al (2006): knowledge of pop music trivia (the graph of which can seen here). As pop music is the kind of thing people have more experience learning and talking about with others, it is a good candidate for a case when these judgments might be more accurate because people do have more access to the relevant information.

The important point to take away from this research is that people don’t appear to be particularly good at judging their abilities relative to others, and this obtains regardless of whether the judges are themselves skilled or unskilled. At least for most of the contexts studied, anyway; it’s perfectly plausible that people – again, skilled and unskilled – will be better able to judge their relative (and absolute) performance when they have experience with a domain in question and have received meaningful feedback on their performance. This is why people sometimes drop out of a major or job after receiving consistent negative feedback, opting to believe they aren’t as cut out for it instead of persisting to believe they are actually above average in that context. You will likely see the least miscalibration for domains where people’s judgments of their ability need to hit reality and there are consequences for being wrong.

References: Burson, K., Larrick, R., & Klayman, J. (2006). Skilled or unskilled, but still unaware of it: How perceptions of difficulty drive miscalibration in relative comparisons. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 90, 60-77.

Kruger, J. & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 77, 1121-1134.