Not a good representation of poverty when people usually don’t use cash anymore

Why are poor people poor? Your answer to that question determines a lot about your feelings and response towards them. If you think people are poor because they’re good social investments who happen to be experiencing a patch of bad luck outside of their control – in other words, that their poverty isn’t really their fault – your interest in seeing that they receive assistance increases. (http://popsych.org/who-

God helps those who can help him later

The extent to which people differ in their desire to help the poor, then, likely varies with the attributions they make for poverty: If people largely believe poverty isn’t the fault of the poor, they will favor helping the poor more broadly, while those who believe poverty is the fault of the poor will disfavor helping them, in general. This divide should go a long way to explaining why, in the US, Liberals tend to favor social programs for helping the poor more than conservatives. Indeed, that precise pattern popped up in a recent paper by Cooley et al (2019) when participants read the following description of a made-up poor person:

Kevin, a[n]…American living in New York City, would say his life has been defined by poverty. As a child, Kevin was raised by a single mom who struggled to balance several part-time jobs simply to pay the bills. Most winters, they had no heat; and, it was a daily question whether they would have enough to eat. In late 2016, Kevin began to receive welfare assistance. Since then, he has not applied for any jobs and instead has cycled between jail cells, shelters, emergency rooms and the streets. Although Kevin would like to be financially independent, he doesn’t feel he has the skills or ability to obtain a well-paying job.

The results found that as political liberalism increased in people, they tended to both report more sympathy for Kevin, as well as making more external attributions for the causes of that poverty. Liberals were more interested in helping because they blamed Kevin less for his circumstances.

If you fancy yourself a liberal, take this time to pat yourself on the back for caring about Kevin’s plight. Good for you. If you fancy yourself a conservative, you can also take this time to pat yourself on the back for your realism about why Kevin is poor.

Now if that was all there was to this study, there might not be too much to talk about. However, the focus of this paper was more specific than general attitudes about poverty and political affiliation. Instead, the authors also looked at Kevin’s race: What happens when Kevin is described as White or Black in that opening sentence? As it turns out…nothing. While both liberals and conservatives were modestly more sympathetic towards a Black Kevin’s plight, these differences weren’t significant. Race didn’t seem to enter the equation when people were looking at this specific example of a poor person. That should be a good thing, I would think; people where judging Kevin as Kevin, rather than as a proxy for his entire race.

Again, if that’s all there was to this study, there might still not be much to talk about. It’s in the final twist of the experiment that brings it all home: how do people respond to a white/black Kevin after reading a bit about white privilege?

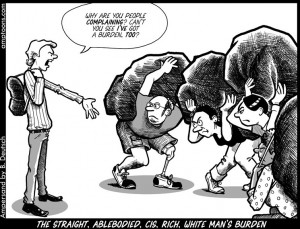

See how everyone’s angry here? That’s called foreshadowing

The experiment (number 2 in the paper) went as follows: 650 Participants would begin by reading a story. This story was either about the importance of a daily routine (the neutral control condition) or about white privilege (the experimental condition). Specifically, the privilege story read:

In America, there is a long history of White people having more power than other racial groups (e.g., Black people). Although many people think of racial inequality as decreasing, there are still privileges that are experienced by White Americans that are not true for other racial groups. For example, in her essay “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” Peggy McIntosh, PhD, lists different privileges that she experiences as a White person living in America.

Four specific examples were provided, including being able to be in the company of people of your same race most of the time, see your race widely and positively presented in the media, not being asked to speak on behalf of your racial group, and not having your race work against you if you need legal or medical help.

Once participants had read that story, they were then presented with the Kevin story from above, asked to respond about how much sympathy they felt for him and how much they blamed him for his situation before finally completing some demographic measures. This allowed the authors to probe what effect this brief discussion of white privilege had on people’s responses.

As it turned out, the conservatives didn’t seem to take much away from that brief lesson on privilege: On a scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 100 (strongly agree), Conservatives reported an equal amount of sympathy for Kevin whether he was white or black (M = 59 for white and M = 61 for Black). As these numbers mirrored the values reported for Conservatives in the control condition well, we could conclude that Conservatives didn’t seem to care about the privilege talk.

The liberals were listening, on the other hand. In the experiment condition, they reported more sympathy for the Black Kevin (M = 76) than the white one (M = 60). So liberals and conservatives seemed to “agree” about how much sympathy white Kevin deserved, while liberals cared more about black Kevin. Does that mean the privilege lesson made liberals care about Black Kevin more? Not at all. When examining the control condition, the most interesting finding was made clear: when they were simply reading about routines, liberals cared as much about White Kevin (M = 71) as Black Kevin (M = 74). Comparing the numbers from the control and experimental groups, we see the following pattern of results emerge: when not thinking about white privilege, liberals cared more about poor people than conservatives and neither seemed to care about race. When white privilege was added to the equation, the only difference that emerged is that only liberals started to care less about White Kevin and blamed him more for this problems without showing any increase in care for Black Kevin.

“At least I didn’t help that poor white guy, which makes me a good person”

In sum, it looked like briefly reading about white privilege made liberals more conservative in their responses towards poor white people. It was a purely negative effect, with no apparent benefits for poor black people. Conservatives, on the other hand, remained consistent, suggesting the privilege talks weren’t doing any good there either. While it is only speculative, it is not hard to imagine how these effects might carry into other domains – like gender – or how they might be made more extreme when the discussion of white privilege isn’t limited to a short passage but instead begins to take up increasingly larger portions of social discourse. If this results in less care for certain groups without a corresponding increase in care for others, it should be a cause for concern to anyone interested in seeing poverty addressed effectively. It might also be a concern if your interest is in treating people as individuals, instead of as proxies for an entire group of people

References: Cooley, E., Brown-Iannuzzi, J., Lei, R., & Cipolli, W. (2019). Complex Intersections of Race and Class: Among Social Liberals, Learning About White Privilege Reduces Sympathy, Increases Blame, and Decreases External Attributions for White People Struggling With Poverty. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/xge0000605