I don’t think it’s a stretch to make the following generalization: people want to feel good about themselves. Unfortunately for all of us, our value to other people tends to be based on what we offer them and, since our happiness as a social species tends to be tethered to how valuable we are perceived to be by others, being happy can be more of chore than we would prefer. These valuable things need not be material; we could offer things like friendship or physical attractiveness, pretty much anything that helps fill a preference or need others have. Adding to the list of misfortunes we must suffer in the pursuit of happiness, other people in the world also offer valuable things to the people we hope to impress. This means that, in order to be valuable to others, we need to be particularly good at offering things to others people: either through being better at providing something than many people provide, or able to provide something relatively unique that others typically don’t. If we cannot match the contributions of others, then people will not like to spend time with us and we will become sad; a terrible fate indeed. One way to avoid that undesirable outcome, then, is to increase your level of competition to become more valuable to other people; make yourself into the type of person others find valuable. Another popular route, which is compatible with the first, is to condemn other people who are successful or promote the images of successful people. If there’s less competition around, then our relative ability becomes more valuable. On that note, Barbie is back in the news again.

“Finally; a new doll for my old one to tease for not meeting her standards!”

The Lammily doll has been making the rounds on various social media sites, marketed as the average Barbie, with the tag line: “average is beautiful”. Lammily is supposed to be proportioned so as to represent the average body of a 19-year-old woman. She also comes complete with stickers for young girls to attach to her body in order to give her acne, scars, cellulite, and stretch marks. The idea here seems to be that if young girls see a more average-looking doll, they will compare themselves less negatively to it and, hopefully, end up feeling better about their body. Future incarnations of the doll are hoped to include diverse body types, races, and I presume other features upon which people vary (just in case the average doll ends up being too alienating or high-achieving, I think). If this doll is preferred by girls to Barbie, then by all means I’m not going to tell them they shouldn’t enjoy it. I certainly don’t discourage the making of this doll or others like it. I just get the sense that the doll will end up primarily making parents feel better by giving them the sense they’re accomplishing something they aren’t, rather than affecting their children’s perceptions.

As an initial note, I will say that I find it rather strange that the creator of the doll stated: “By making a doll real I feel attention is taken away from the body and to what the doll actually does.” The reason I find that strange is because the doll does not, as far as I can see, come with a number of different accessories that make it do different things. In fact, if Lammily does anything, I’m not sure what that anything is, as it’s never mentioned. The only accessory I see are the aforementioned stickers to make her look different. Indeed, the whole marketing of the doll is focuses on how it looks; not what it does. For a doll ostensibly attempting to take attention away from the body, it’s body seems to be its only selling point.

The main idea, rather, as far as I can tell, is to try and remove the possible intrasexual competition over appearance that women might feel when confronted with a skinny, attractive, makeup-clad figure. So, by making the doll less attractive with scar stickers, girls will feel less competition to look better. There are a number of facets of the marketing of the doll that would support this interpretation: one such point is the tag line. Saying that “average is beautiful” is, from a statistical standpoint, kind of strange; it’s a bit like saying “average is tall” or “average is smart”. These descriptors are all relative terms – typically ones that apply to upper-ends of some distribution – so applying them to more people would imply that people don’t differ as much on the trait in question. The second point to make about the tagline is that I’m fairly certain, if you asked him, the creator of the Lammily doll – Nickolay Lamm - would not tell you he meant to imply that women who are above or below some average are not beautiful; instead, you’d probably get some sentiment to the effect that everyone is attractive and unique in their own special way, further obscuring the usefulness of the label. Finally, if the idea is to “take attention away from the body”, then selling the doll under the label of its natural beauty is kind of strange.

So does Barbie have a lot to answer for culturally, and is Lammily that answer? Let’s consider some evidence examining whether Barbie dolls are actually doing harm to young girl in the first place and, if they are, whether that harm might be mitigated via the introduction of more-proportionate figures.

“If only she wasn’t as thin, this never would have happened”

One 2006 paper (Dittmar, Halliwell, & Ive, 2006) concludes that the answer is “yes” to both those questions, though I have my doubts. In their paper, the researchers exposed 162 girls between the ages of 5 and 8 to one of three picture books. These books contained a few images of Barbie (who would be a US dress size 2) or Emme (a size 16) dolls engaged in some clothing shopping; there was also a control book that did not draw attention to bodies. The girls were then asked questions about how they looked, how they wanted to look, and how they hoped to look when they grew up. After 15 minutes of exposure to these books, there were some changes in these girl’s apparent satisfaction with their bodies. In general, the girls exposed to the Barbies tended to want to be thinner than those exposed to the Emme dolls. By contrast, those exposed to Emme didn’t want to be thinner than those exposed to no body images at all. In order to get a sense for what was going on, however, those effects require some qualifications

For starters, when measuring the difference between one’s perception of her current body and her current ideal body, exposure to Barbie only made the younger children want to be thinner. This includes the girls in the 5 – 7.5 age range, but not the girls in the 7.5 – 8.5 range. Further, when examining what the girl’s ideal adult bodies would be, Barbie had no effect on the youngest girls (5 – 6.5) or the oldest ones (7.5 – 8.5). In fact, for the older girls, exposure to the Emme doll seemed to make them want to be thinner as adults (the authors suggesting this to be the case as Emme might represent a real, potential outcome the girls are seeking to avoid). So these effects are kind of all over the place, and it is worth noting that they, like many effects in psychology, are modest in size. Barbie exposure, for instance, reduced the girls “body esteem” (a summed measure of six questions about the girl felt about their bodies that got a 1 to 3 response, with 1 being bad, 2 neutral, and 3 being good) from a mean of 14.96 in the control condition to 14.45. To put that in perspective, exposure to Barbie led to girls, on average, moving one response out of six half a point on a small scale, compared to the control group.

Taking these effects at face value, though, my larger concerns with the paper involve a number of things it does not do. First, it doesn’t show that these effects are Barbie-specific. By that I don’t mean that they didn’t compare Barbie against another doll – they did – but rather that they didn’t compare Barbie against, say, attractive (or thin) adult human women. The authors credit Barbie with some kind of iconic status that is likely playing an important role in determining girl’s later ideals of beauty (as opposed to Barbie temporarily, but not lastingly, modifying it their satisfaction), but they don’t demonstrate it. On that point, it’s important to note what the authors are suggesting about Barbie’s effects: that Barbies lead to lasting changes in perceptions and ideals, and that the older girls weren’t being affected by exposures to Barbies because they have already ”…internalized [a thin body ideal] as part of their developing self-concept” by that point.

At least you got all that self-deprecation out of the way early

An interesting idea, to be sure. However, it should make the following prediction: adult women exposed to thin or attractive members of the same sex shouldn’t have their body satisfaction affected, as they have already “internalized a thin ideal”. Yet this is not what one of the meta-analysis papers cited by the authors themselves finds (Groesz, Levine, & Murnen, 2002). Instead, adult women faced with thin models feel less satisfied with their bodies relative to when they view average or above-average weight models. This is inconsistent with the idea that some thin beauty standard has been internalized by age 8. Both sets of data, however, are consistent with the idea that exposure to an attractive competitor might reduce body satisfaction temporarily, as the competitor will be perceived to be more attractive by other people. In much the same way, I might feel bad about my skill at playing music when I see someone much better at the task than I am. I would be dissatisfied because, as I mentioned initially, my value to others depends on who else happens to offer what I do: if they’re better at it, my relative value decreases. A little dissatisfaction, then, either pushes me to improve my skill or to find a new domain in which I can compete more effectively. The disappointment might be painful to experience, but it is useful for guiding behavior. If the older girls just stopped viewing Barbie as competition, perhaps, because they have moved onto new stages in their development, this would explain why Barbie had no effect on them as well. The older girls might simply have grown out of competing with Barbie.

Another issue with the paper is that the experiment used line drawings of body shapes, rather than pictures of actual human bodies, to determine which body girls think they have and which body they want, both now and in the future. This could be an issue, as previous research (Tovee & Cornelissen, 2001) failed to replicate the “girls want to be skinnier than men would prefer” effects – which were found using line drawings – when using actual pictures of human bodies. One potential reason for that different in findings is that a number of features besides thinness might unintentionally co-vary in these line drawings. So some of the desire to be skinny that the girls were expressing in the 2006 experiment might have just been an artifact of the stimulus materials being used.

Additionally, Dittmar, Halliwell, & Ive (2006), somewhat confusingly, didn’t ask the girls about whether or not they owned Barbies or how much exposure they had to them (though they do note that it probably would have been a useful bit of information to have). There are a number of predictions we might make about such a variable. For instance, girls exposed to Barbie more often should be expected to have a greater desire for thinness, if the author’s account is true. Further still, we might also predict that, among girls who have lots of experience with Barbies, a temporary exposure to pictures of Barbie shouldn’t be expected to effect their perception of their ideal body much, if at all. After all, if they’re constantly around the doll, they should have, as the authors put it, already “…internalized [a thin body ideal] as part of their developing self-concept”, meaning that additional exposure might be redundant (as it was with the older girls). Since there’s no data on the matter, I can’t say much more about it.

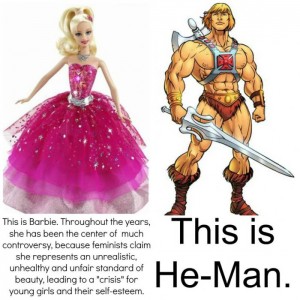

A match made in unrealistic heaven.

So would a parent have a lasting impact on their daughter’s perception of beauty by buying her a Barbie? Probably not. The current research doesn’t demonstrate any particularly unique, important, or lasting role for Barbie in the development of children’s feelings about their bodies (thought it does assume them). You probably won’t do any damage to your child by buying them an Emme or a Lammily either. It is unlikely that these dolls are the ones socializing children and building their expectations of the world; that’s a job larger than one doll could ever hope to accomplish. It’s more probable that features of these dolls reflect (in some cases exaggerated) aspects of our psychology concerning what is attractive, rather than creating them.

A point of greater interest I wanted to end with, though, is why people felt that the problem which needed to be addressed when it came to Barbie was that she was disproportionate. What I have in mind is that Barbie has a long history of prestigious careers; over 150 of them, most of which being decidedly above-average. If you want a doll that focuses on what the character does, Barbie seems to be doing fine in that regard. If we want Barbie to be an average girl sure, she won’t be as thin, but then chances are that she doesn’t even have her Bachelor’s degree either, which would preclude her from a number of the professions she has held. She’s also unlikely to be a world class athlete or performer. Now, yes, it is possible for people to hold those professions while it is impossible for anyone to be proportioned as Barbie is, but it’s certainly not the average. Why is the concern over what Barbie looks like, rather than what unrealistic career expectations she generates? My speculation is that the focus arises because, in the real world, women compete with each other more over their looks than their careers in the mating market, but I don’t have time to expand on that much more here.

It just seems peculiar to focus on one particular non-average facet of reality obsessively only to state that it doesn’t matter. If the debate over Barbie can teach us anything, it’s that physical appearance does matter; quite a bit, in fact. To try and teach people – girls or boys – otherwise might help them avoid some temporary discomfort (“Looks don’t matter; hooray!”), but it won’t give them an accurate impression of how the wider world will react to them (“Yeah, about that whole looks thing…”); a rather dangerous consequence, if you ask me.

References: Dittmar, H., Halliwell, E., & Ive, S. (2006). Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls. Developmental Psychology, 42, 283-292.

Groesz, L., Levine, M., & Murnen, S. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A metaanalytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 1–16.

Tovee, M. & Cornelissen, P. (2001). Female and male perceptions of physical attractiveness in front-view and profile. British Journal of Psychology, 92, 391-402.