Though I don’t make a habit of watching many shows, I do often catch some funny clips of them that have been posted online. One that I saw semi-recently (which I feel relates to the present post) is a clip from Portlandia. In this video, people are writing a magazine issue about a man living a life that embodies manhood. In this case, they select a man who used to work at an office, but then left his job and now makes furniture. While everyone is really impressed with the idea, it eventually turns out that the man in question does make furniture…but it’s terrible. Faced with the revelation that the man’s work isn’t good – that it probably wasn’t worth leaving his job to do something he’s bad at – the people in question aren’t impressed by his over-confidence in pursuing his furniture work. They don’t seem to find him more attractive because he was overconfident; quite the opposite in fact. The key determent of his attractiveness was the actual quality of his work. In other words, since he couldn’t back up his confidence with his efforts, the ratings of his attractiveness appeared to drop precipitously.

It might not be comfortable, but at least it’s hand-made

What we can learn from an example like this is that something like overconfidence per se – being more confident than one should be and behaving in ways one rightfully shouldn’t because of it – doesn’t appear to be impressive to potential mates. As such, we might expect that people who pursue activities they aren’t well suited for tend to do worse in the mating domain than those who are able to exist within a niche they more suitably fill: if you can’t cut it as a craftsman, better to keep that steady, yet less-interesting office job. This is largely a factor of the overconfident investing their time and effort into pursuits that do not yield positive benefits for them or others. You can think of it like playing the lottery, in a sense: if you are overly-confident that you’ll win the lottery, you might incorrectly invest money into lottery tickets that you could otherwise spend on pursuits that don’t amount to lighting it on fire.

This is likely why the research on the (over)perception of sexual intent turns out the way it does. I’ve written about the topic before, but to give you a quick overview of the main points: researchers have uncovered that men tend to perceive more sexual interest in women than women themselves report having. To put that in a simple example, if you were to ask a woman, “given you were holding a man’s hand, how sexually interested in him are you?” you’ll tend to get a different answer than if you ask a man, “given that a woman was holding your hand, how sexually interested do you think she is in you?” In particular, men tend to think behaviors like hand-holding signal more sexual intent than women report. These kinds of results have been chalked up to men overperceiving sexual intent, but more recent research puts a different spin on the answers: specifically, if you were to ask a woman, “given that another woman (who is not you) is holding a man’s hand, how sexually interested in him do you think she is?” the answers from the women now align with those of the men. Women (as well as men) seem to believe that other women will underreport their sexual intent, while believing their own self-reports are accurate. Taken together, then, both men and women seem to perceive more sexual intent in a woman’s behavior than the woman herself reports. Rather than everyone else overperceiving sexual intent, it seems a bit more probable that women themselves tend to underreport their own sexual intent. In a sentence, women might play a little coy, rather than everyone else in the world being wrong about them.

Today, I wanted to talk about a very recent paper (Murray et al, 2017) by some of the researchers who seem to favor the overperception hypothesis. That is, they seem to suggest that women honestly and accurately report their own sexual interest, but everyone else happens to perceive it incorrectly. In particular, their paper represents an attempt to respond to the point that women overperceive the sexual intent of other women as well. At the outset, I will say that I find the title of their research rather peculiar and their interpretation of the data rather strange (points I’ll get to below). Indeed, I found both things so strange that I had to ask around a little first before I stared writing this post to ensure that I wasn’t misreading something, as I know smart people wrote the paper in question and the issues seemed rather glaring to me (and if a number of smart people seem to be mistaken, I wanted to make sure the error wasn’t simply something on my end first). So let’s get into what was done in the paper and why I think there are some big issues.

“…Am I sure I’m not the crazy one here, because this seems real strange”

Starting out with what was done, Murray et al (2017) collected data from 414 heterosexual women online. These women answered questions about 15 different behaviors which might signal romantic interest. They were first asked these questions about themselves, and then about other women. So, for instance, a woman might be asked, “If you held hands with a man, how likely is it you intend to have sex with him?” They would then be asked the same hand-holding question, but about other women: “If a woman (who is not you) held hands with a man, how likely is it that she would…” and then end with something along the lines of, “say she wants to have sex with him,” or “actually want to have a sex with him.” They were trying to tap this difference between the perceptions of “what women will say” and “what women actually want” responses. They also wanted to see what happened when you ask the “say” or “want” question first.

Crucially, the previous research these authors are responding to found that both men and women tend to report that, in general, women tend to want more than they say. The present research was only looking at women, but it found that same pattern: regardless of whether you ask the “say” or “want” questions first, women seem to think that other women will say they are less interested than they actually are. In short, women believe other women to be at least somewhat coy. In that sense, these results are a direct replication of the previous findings.

One of the things I find strange about the paper, then, is the title: “A Preregistered Study of Competing Predictions Suggests That Men Do Overestimate Women’s Sexual Intent.” Since this study was only looking at women, the use of “men” in the title seems poorly thought out. I assume the intentions of the authors were to say that these results are consistent with the idea that men also overperceive, but even in that case it really ought to say “People Overestimate,” rather than “Men Do.” I earnestly can’t think of a reason to single out the male gender in the title other than the possibility that the authors seem to have forgotten they were measuring something other than what they actually wanted to. That is, they wanted their results to speak to the idea that male perceptions are biased upwards (in order support their own, prior work), but they seem to be a bit overeager to do so and jumped the gun.

“Well women are basically men anyway, right? Close enough”

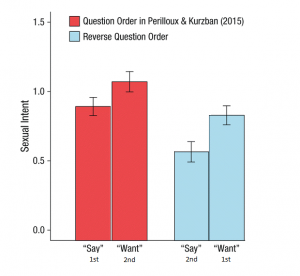

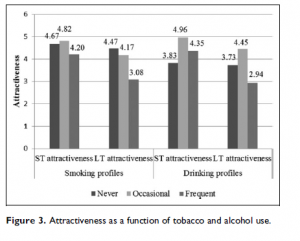

Another point I find rather curious from the paper – some data the authors highlight – is that the women’s responses did depend (somewhat) on whether you ask the “say” or “want” questions first. Specifically, the responses to both the “say” and “want” scales are a little lower when the “want” question is asked first. However, the relative pattern of the data – the effect of perceived coyness – exists regardless of the order. I’ve attached a slightly-modified version of their graph below so you can see what their results look like.

What this suggests to me is that something of an anchoring effect exists, whereby the question order might affect how people interpret the values on the scale of sexual intent (which goes from 1 to 7). What it does not suggest to me is what Murray et al (2017) claim it does:

“These results support the hypothesis that women’s differential responses to the “say” and “want” questions in Perilloux and Kurzban’s study were driven by question-order effects and language conventions, rather than by women’s chronic underreporting of their sexual intentions.”

As far as I can tell, they do nothing of the sort. Their results – to reiterate – are effectively direct replications of what Perilloux & Kurzban found. Regardless of the order in which you ask the questions, women believed other women wanted more than they would let on. How that is supposed to imply that the previously (and presently) observed effects are due to questioning ordering are beyond me. To convince me this was simply an order effect, data would need to be presented that either (a) showed the effect goes away when the order of the questions is changed or (b) showed the effect changes direction when the question order is changed. Since neither of those things happened, I’m hard pressed to see how the results can be chalked up to order effects.

For whatever reason, Murray et al (2017) seem to make a strange contrast on that front:

We predicted that responses to the “say” and “want” questions would be equivalent when they were asked first, whereas Perilloux and Kurzban confirmed their prediction that ratings for the “want” question would be higher than ratings for the “say” question regardless of the order of the questions”

Rather than being competing hypotheses, these two seem like hypotheses that could both be true: you could see that people interpret the values on the scales differently, depending on which question you ask first while also predicting that the ratings for “want” questions will be higher than those for “say” questions, regardless of the order. Basically, I have no idea why the word “whereas” was inserted into that passage, as if to suggest both of those things could not be true (or false) at the same time (I also have no idea why the word “competing” was inserted into the title of their paper, as it seems equally inappropriate there as the word “men”). Both of those hypotheses clearly can both be true and, indeed, seem to be if these results are taken at face value.

“They predict this dress contains the color black, whereas we predict it contains white”

To sum up, the present research by Murray et al (2017) doesn’t seem to suggest that women (and, even though they didn’t look at them in this particular study, men) overperceive other women’s sexual intentions. If anything, it suggests the opposite. Indeed, as their supplementary file points out, “…across both experimental conditions women reported their own sexual intentions to be significantly lower than both what other women say and what they actually want,” and, “…it seems that when reporting on their own behavior, the most common responses for acting either less or more interested are either never engaging in this behavior or sometimes doing so, whereas women seem to believe that other women most commonly engage in both behaviors some of the time.”

So, not only do women believe that other women (who aren’t them) engage in this coy behavior more often than they themselves do (which would be impossible, as not everyone can think that about everyone else and be right), but women also even admit to, at least sometimes, acting less interested than they actually are. When women are actually reporting that, “Yes, I have sometimes underreported my sexual interest,” well, that seems to make the underreporting hypothesis sound a bit more plausible. The underreporting hypothesis would also be consistent with the data that finds women tend to underreport their number of sexual partners when they think others might see that report or lies will not be discovered; by contrast, male reports of partner numbers are more consistent (Alexander & Fisher, 2003).

Perhaps the great irony here, then, is the Murray et al (2017) might have been a little overeager to interpret their results in a certain fashion, and so end up misinterpreting their study as speaking to men (when it only looks at women) and their hypothesis as being a competing one (when it is not). There are costs to being overeager, just as there are costs to being overconfident; better to stick with appropriate eagerness or confidence to avoid those pitfalls.

References: Alexander MG, & Fisher TD (2003). Truth and consequences: using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self-reported sexuality. Journal of sex research, 40 (1), 27-35

Murray, D., Murphy, S., von Hippel, W., Trivers, R., & Haselton, M. (2017). A preregistered study of competing predictions suggests that men do overestimate women’s sexual intent. Psychological Science.