If the view counts on previous posts have been any indication, people really do enjoy reading about, understanding, and – perhaps more importantly – overcoming the obstacles found on the dating terrain; understandably so, given its greater personal relevance to their lives. In the interests of adding some value to the lives of others, then, today I wanted to discuss some research examining the connection between recreational drug use and sexual behavior in order to see if any practical behavioral advice can be derived from it. The first order of business will be to try and understand the relationship between recreational drugs and mating from an evolutionary perspective; the second will be to take a more direct look at whether drug use has positive and negative effects when it comes to attracting a partner, and in what contexts those effects might exist. In short, will things like drinking and smoking make you smoking hot to others?

So far selling out has been unsuccessful, so let’s try talking sex

We can begin by considering why people care so much about recreational drug use in general: from historical prohibitions on alcohol to modern laws prohibiting the possession, use, and sale of drugs, many people express a deep concern over who gets to put what into their body at what times and for what reasons. The ostensibly obvious reason for this concern that most people will raise immediately is that such laws are designed to save people from themselves: drugs can cause a great degree of harm to users and people are, essentially, too stupid to figure out what’s really good for them. While perceptions of harm to drug users themselves no doubt play a role in these intuitions, they are unlikely to actually be whole story for a number of reasons, chief among which is that they would have a hard time explaining the connection between sexual strategies and drug use (and that putting people in jail probably isn’t all that good for them either, but that’s another matter). Sexual strategies, in this case, refer roughly to an individual’s degree of promiscuity: some people preferentially enjoy engaging in one or more short-term sexual relationships (where investment is often funneled to mating efforts), while others are more inclined towards single, long-term ones (where investment is funneled to parental efforts). While people do engage in varying degrees of both at times, the distinction captures the general idea well enough. Now, if one is the type who prefers long-term relationships, it might benefit you to condemn behaviors that encourage promiscuity; it doesn’t help your relationship stability to have lots of people around who might try to lure your mate away or reduce the confidence of a man’s paternity in his children. To the extent that recreational drug use does that (e.g., those who go out drinking in the hopes of hooking up with others owing to their reduced inhibitions), it will be condemned by the more long-term maters in turn. Conversely, those who favor promiscuity should be more permissive towards drug use as it makes enacting their preferred strategy easier.

This is precisely the pattern of results that Quintelier et al (2013) report: in a cross-cultural sample of Belgians (N = 476), Dutch (N = 298), and Japanese (N = 296) college students who did not have children, even after controlling for age, sex, personality variables, political ideology, and religiosity, attitudes towards drug use were still reliably predicted by participant’s sexual attitudes: the more sexually permissive one was, the more they tended to approve of drug use. In fact, sexual attitudes were the best predictors of people’s feelings about recreational drugs both before and after the controls were added (findings which replicated a previous US sample). By contrast, while the non-sexual variables were sometimes significant predictors of drug views after controlling for sexual attitudes, they were not as reliable and their effects were not as large. This pattern of results, then, should yield some useful predictions about how drug use effects your attractiveness to other people: those who are looking for short-term sexual encounters might find drug use more appealing (or at least less off-putting), relative to those looking for long-term relationships.

“I pronounce you man and wife. Now it’s time to all get high”

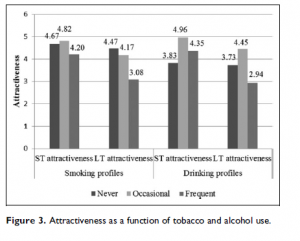

Thankfully, I happen to have a paper on hand that speaks to the matter somewhat more directly. Vincke (2016) sought to examine how attractive brief behavioral descriptions of men were rated as being by women for either short- or long-term relationships. Of interest, these descriptions included the fact that the man in question either (a) did not, (b) occasionally, or (c) frequently smoke cigarettes or drink alcohol. A sample of 240 Dutch women were recruited and asked to rate these profiles with respect to how attractive the men in question would be for either a casual or committed relationship and whether they thought the men themselves were more likely to be interested in short/long-term relationships.

Taking these in reverse order, the women rated the men who never smoked as somewhat less sexually permissive (M = 4.31, scale from 1 to 7) than those who either occasionally or frequently did (Ms = 4.83 and 4.98, respectively; these two values did not significantly differ). By contrast, those who never drank or occasionally did were rated as being comparably less permissive (Ms = 4.04) than the men who drank frequently (M = 5.17). Drug use, then, did effect women’s perceptions of men’s sexual interests (and those perceptions happen to match reality, as a second study with men confirmed). If you’re interested in managing what other people think your relationship intentions are, then, managing your drug use accordingly can make something of a difference. Whether that ended up making the men more attractive is a different matter, however.

As it turns out, smoking and drinking appear to look distinct in that regard: in general, smoking tended to make men look less attractive, regardless of whether the mating context was short- or long-term, and frequent smoking was worse than occasional smoking. However, the decline in attractiveness from smoking was not as large in short-term contexts. (Oddly, Vincke (2016) frames smoking as being an attractiveness benefit in short-term contexts within her discussion when it’s really just less of a cost. The slight bump seen in the data is neither statistically or practically significant) This pattern can be seen in the left half of the author’s graph.  By contrast – on the right side – occasional drinkers were generally rated as more attractive than men who never or frequently drank across conditions across both short- and long-term relationships. However, in the context of short-term mating, frequent drinking was rated as being more attractive than never drinking, whereas this pattern reversed itself for long-term relationships. As such, if you’re looking to attract someone for a serious relationship, you probably won’t be impressing them much with your ability to do keg stands of liquor, but if you’re looking for someone to hook up with that night it might be better to show that off than sip on water all evening.

By contrast – on the right side – occasional drinkers were generally rated as more attractive than men who never or frequently drank across conditions across both short- and long-term relationships. However, in the context of short-term mating, frequent drinking was rated as being more attractive than never drinking, whereas this pattern reversed itself for long-term relationships. As such, if you’re looking to attract someone for a serious relationship, you probably won’t be impressing them much with your ability to do keg stands of liquor, but if you’re looking for someone to hook up with that night it might be better to show that off than sip on water all evening.

Cigarettes and alcohol look different from one another in the attractiveness domain even though both might be considered recreational drug use. It is probable that what differentiates them here is their effects on encouraging promiscuity, as previously discussed. While people are often motivated to go out drinking in order to get intoxicated, lose their inhibitions, and have sex, the same cannot usually be said about smoking cigarettes. Singles don’t usually congregate at smoking bars to meet people and start relationships, short-term or otherwise (forgoing for the moment that smoking bars aren’t usually things, unless you count the rare hookah lounges). Smoking might thus make men appear to be more interested in casual encounters because it cues a more general interest in short-term rewards, rather than anything specifically sexual; in this case, if one is willing to risk the adverse health effects in the future for the pleasure cigarettes provide today, then it is unlikely that someone would be risk averse in other areas of their life.

If you want to examine sex specifically, you might have picked the wrong smoke

There are some limitations here, namely that this study did not separate women in terms of what they were personally seeking in terms of relationships or their own interests/behaviors when it comes to engaging in recreational drug use. Perhaps these results would look different if you were to account for women’s smoking/drinking habits. Even if frequent drinking is a bad thing for long-term attractiveness in general, a mismatch with the particular person you’re looking to date might be worse. It is also possible that a different pattern might emerge if men were assessing women’s attractiveness, but what differences those would be are speculative. It is unfortunate that the intuitions of the other gender didn’t appear to be assessed. I think this is a function of Vincke (2016) looking for confirmatory evidence for her hypothesis that recreational drug use is attractive to women in short-term contexts because it entails risk, and women value risk-taking more in short-term male partners than long-term ones. (There is a point to make about that theory as well: while some risky activities might indeed be more attractive to women in short-term contexts, I suspect those activities are not preferred because they’re risky per se, but rather because the risks send some important cue about the mate quality of the risk taker. Also, I suspect the risks need to have some kind of payoff; I don’t think women prefer men who take risks and fail. Anyone can smoke, and smoking itself doesn’t seem to send any honest signal of quality on the part of the smoker.)

In sum, the usefulness of these results for making any decisions in the dating world is probably at its peak when you don’t really know much about the person you’re about to meet. If you’re a man and you’re meeting a woman who you know almost nothing about, this information might come in handy; on the other hand, if you have information about that woman’s preferences as an individual, it’s probably better to use that instead of the overall trends.

References: Quintelier, K., Ishii, K., Weeden, J., Kurzban, R., & Braeckman, J. (2013). Individual differences in reproductive strategy are related to views about recreational drug use in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Japan. Human Nature, 24, 196-217.

Vincke, E. (2016). The young male cigarette and alcohol syndrome: Smoking and drinking as a short-term mating strategy. Evolutionary Psychology, 1-13.