Imagine for a moment that you’re in charge of overseeing medical research approval for ethical concerns. One day, a researcher approaches you with the following proposal: they are interested in testing whether a food stuff that some portion of the population occasionally consumes for fun is actually quite toxic, like spicy chilies. They think that eating even small doses of this compound will cause mental disturbances in the short term – like paranoia and suicidal thoughts – and might even cause those negative changes permanently in the long term. As such, they intend to test their hypothesis by bringing otherwise-healthy participants into the lab, providing them with a dose of the possibly-toxic compound (either just once or several times over the course of a few days), and then see if they observe any negative effects. What would your verdict on the ethical acceptability of this research be? If I had to guess, I suspect that many people would not allow the research to be conducted because one of the major tenants of research ethics is that harm should not befall your participants, except when absolutely necessary. In fact, I suspect that were you the researcher – rather than the person overseeing the research – you probably wouldn’t even propose the project in the first place because you might have some reservations about possibly poisoning people, either harming them directly and/or those around them indirectly.

“We’re curious if they make you a danger to yourself and others. Try some”

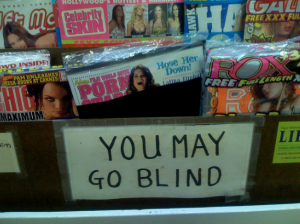

With that in mind, I want to examine a few other research hypotheses I have heard about over the years. The first of these is the idea that exposing men to pornography will cause a number of harmful consequences, such as increasing how appealing rape fantasies were, bolstering the belief that women would enjoy being raped, and decreasing the perceived seriousness of violence against women (as reviewed by Fisher et al, 2013). Presumably, the effect on those beliefs over time is serious as it might lead to real-life behavior on the part of men to rape women or approve of such acts on the parts of others. Other, less-serious harms have also been proposed, such as the possibility that exposure to pornography might have harmful effects on the viewer’s relationship, reducing their commitment, making it more likely that they would do things like cheat or abandon their partner. Now, if a researcher earnestly believed they would find such effects, that the effects would be appreciable in size to the point of being meaningful (i.e., are large enough to be reliably detected by statistical test in relatively small samples), and that their implications could be long-term in nature, could this researcher even ethically test such issues? Would it be ethically acceptable to bring people into the lab, randomly expose them to this kind of (in a manner of speaking) psychologically-toxic material, observe the negative effects, and then just let them go?

Let’s move onto another hypothesis that I’ve been talking a lot about lately: the effects of violent media on real life aggression. Now I’ve been specifically talking about video game violence, but people have worried about violent themes in the context of TV, movies, comic books, and even music. Specifically, there are many researchers who believe that exposure to media violence will cause people to become more aggressive through making them perceive more hostility in the world, view violence as a more acceptable means of solving problems, or by making violence seem more rewarding. Again, presumably, changing these perceptions is thought to cause the harm of eventual, meaningful increases in real-life violence. Now, if a researcher earnestly believed they would find such effects, that the effects would be appreciable in size to the point of being meaningful, and that their implications could be long-term in nature, could this researcher even ethically test such issues? Would it be ethically acceptable to bring people into the lab, randomly expose them to this kind of (in a manner of speaking) psychologically-toxic material, observe the negative effects, and then just let them go?

Though I didn’t think much of it at first, the criticisms I read about the classic Bobo doll experiment are actually kind of interesting in this regard. In particular, researchers were purposefully exposing young children to models of aggression, the hope being that the children will come to view violence as acceptable and engage in it themselves. The reason I didn’t pay it much mind is that I didn’t view the experiment as causing any kind of meaningful, real-world, or lasting effects on the children’s aggression; I don’t think mere exposure to such behavior will have meaningful impacts. But if one truly believed that it would, I can see why that might cause some degree of ethical concerns.

Since I’ve been talking about brief exposure, one might also worry about what would happen to researchers were to expose participants to such material – pornographic or violent – for weeks, months, or even years on end. Imagine a study that asked people to smoke for 20 years to test the negative effects in humans; probably not getting that past the IRB. As a worthy aside on that point, though, it’s worth noting that as pornography has become more widely available, rates of sexual offending have gone down (Fisher et al, 2013); as violent video games have become more available, rates of youth violent crime have done down too (Ferguson & Kilburn, 2010). Admittedly, it is possible that such declines would be even steeper if such media wasn’t in the picture, but the effects of this media – if they cause violence at all – are clearly not large enough to reverse those trends.

I would have been violent, but then this art convinced me otherwise

So what are we to make of the fact that these research was proposed, approved, and conducted? There are a few possibility to kick around. The first is that the research was proposed because the researchers themselves don’t give much thought to the ethical concerns, happy enough if it means they get a publication out of it regardless of the consequences, but that wouldn’t explain why it got approved by other bodies like IRBs. It is also possible that the researchers and those who approve it believe it to be harmful, but view the benefits to such research as outstripping the costs, working under the assumption that once the harmful effects are established, further regulation of such products might follow ultimately reducing the prevalence or use of such media (not unlike the warnings and restrictions placed on the sale of cigarettes). Since any declines in availability or censorship of such media have yet to manifest – especially given how access to the internet provides means for circumventing bans on the circulation of information – whatever practical benefits might have arisen from this research are hard to see (again, assuming that things like censorship would yield benefits at all) .

There is another aspect to consider as well: during discussions of this research outside of academia – such as on social media – I have not noted a great deal of outrage expressed by consumers of these findings. Anecdotal as this is, when people discuss such research, they do not appear to raising the concern that the research itself was unethical to conduct because it will doing harm to people’s relationships or women more generally (in the case of pornography), or because it will result in making people more violent and accepting of violence (in the video game studies). Perhaps those concerns exist en mass and I just haven’t seen them yet (always possible), but I see another possibility: people don’t really believe that the participants are being harmed in this case. People generally aren’t afraid that the participants in those experiments will dissolve their relationship or come to think rape is acceptable because they were exposed to pornography, or will get into fights because they played 20 minutes of a video game. In other words, they don’t think those negative effects are particularly large, if they even really believe they exist at all. While this point would be a rather implicit one, the lack of consistent moral outrage expressed over the ethics of this kind of research does speak to the matter of how serious these effects are perceived to be: at least in the short-term, not very.

What I find very curious about these ideas – pornography causes rape, video games cause violence, and their ilk – is that they all seem to share a certain assumption: that people are effectively acted upon by information, placing human psychology in a distinctive passive role while information takes the active one. Indeed, in many respects, this kind of research strikes me as remarkably similar to the underlying assumptions of the research on stereotype threat: the idea that you can, say, make women worse at math by telling them men tend to do better at it. All of these theories seem to posit a very exploitable human psychology capable of being manipulated by information readily, rather than a psychology which interacts with, evaluates, and transforms the information it receives.

For instance, a psychology capable of distinguishing between reality and fantasy can play a video game without thinking it is being threatened physically, just like it can watch pornography (or, indeed, any videos) without actually believing the people depicted are present in the room with them. Now clearly some part of our psychology does treat pornography as an opportunity to mate (else there would be no sexual arousal generated in response to it), but that part does not necessarily govern other behaviors (generating arousal is biologically cheap; aggressing against someone else is not). The adaptive nature of a behavior depends on context.

Early hypotheses of the visual-arousal link were less successful empirically

As such, expecting something like a depiction to violence to translate consistently into some general perception that violence is acceptable and useful in all sorts of interactions throughout life is inappropriate. Learning that you can beat up someone weaker than you doesn’t mean it’s suddenly advisable to challenge someone stronger than you; relatedly, seeing a depiction of people who are not you (or your future opponent) fighting shouldn’t make it advisable for you to change your behavior either. Whatever the effects of this media, they will ultimately be assessed and manipulated internally by psychological mechanisms and tested against reality, rather than just accepted as useful and universally applied.

I have seen similar thinking about information manipulating people another time as well: during discussions of memes. Memes are posited to be similar to infectious agents that will reproduce themselves at the expense of their host’s fitness; information that literally hijacks people’s minds for its own reproductive benefits. I haven’t seen much in the way of productive and successful research flowing from that school of thought quite yet – which might be a sign of its effectiveness and accuracy – but maybe I’m just still in the dark there.

References: Ferguson, C. & Kilburn, J. (2010). Much ado about nothing: The misestimation and overinterpretation of violent video game effects in eastern and western nations: Comment on Anderson et al (2010). Psychological Bulletin, 136, 174-178.

Fisher, W., Kohut, T., Di Gioacchino, L., & Fedoroff , P. (2013). Pornography, sex crime, and paraphilia. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15, 362.

Actually, it seems quite clear that even the Chile study would be ethical.

After all if something is widely believed to be safe and consumed frequently by large numbers then the harm from not documenting it to be unsafe is huge. The utility calculations are clear. It’s immoral not to do studies like this.

Now when the treatment isn’t in use and widely believed to be safe in the same population in which the study is being done things get a little more complicated. A study which feeds US college students a food common in Africa and assumed to be safe but not eaten in the US might, if it turns out to be harmful, undermine American’s belief in the safety of research studies and make them less likely to participate.

However, as long as the treatment is commonly used in the population from which subjects are drawn no one will feel ill used if the study demonstrates the treatment is harmful. Just the opposite, they will be thankful that they now know and they and their loved ones can avoid it from this point on. To be extra safe just tell the subjects you believe it to be dangerous but it isn’t yet proven and it is commonly consumed.

Yes, I know that is not how ERB’s work but philosophers have long raised issues with the principles they apply.

I think it’s fairly accurate to say that ERBs (and similar concerns) aren’t actually trying to reach the ethically correct answer (that’s hard and people can disagree) but the answer that minimizes criticism. So as long as a research program would strike some people as ethically problematic they don’t examine the issue further to see if they are right