There’s been an ongoing debating in the philosophical literature on morality for some time. That debate focuses on whether the morality of an act should be determined on the basis of either (a) the act’s outcome, in terms of its net effects on people’s welfare, or (b) whether the morality of an act is determined by…something else; intuitions, feelings, or what have you (i.e. “Incest is just wrong, even if nothing but good were to come of it”). These stances can be called the consequentialist and nonconsequentialist stances, respectively, and it’s at topic I’ve touched upon before. When I touched on the issue, I had this to say:

There are more ways of being consequentialist than with respect to the total amount of welfare increase. It would be beneficial to turn our eye towards considering strategic welfare consequences that likely to accrue to actors, second parties, and third parties as a result of these behaviors.

In other words, moral judgments might focus not only on the acts per se (the nonconsequentalist aspects) or their net welfare outcomes (the consequences), but also on the distribution of those consequences. Well, I’m happy to report that some very new, very cool research speaks to that issue and appears to confirms my intuition. I happen to know the authors of this paper personally and let me tell you this: the only thing about the authors that are more noteworthy than their good looks and charm is how humble one of them happens to be.

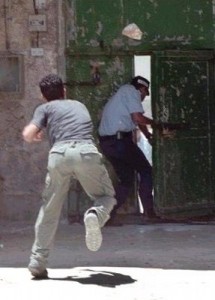

The research (Marczyk & Marks, in press) was examining responses to the classic trolley dilemma and a variant of it. For those not well-versed in the trolley dilemma, here’s the setup: there’s an out-of-control train heading towards five hikers who cannot get out of the way in time. If the train continues on it’s part, then all five wills surely die. However, there’s a lever which can be pulled to redirect the train onto a side track where a single hiker is stuck. If the lever is pulled, the five will live, but the one will die (pictured here). Typically, when asked whether it would be acceptable for someone to pull the switch, the majority of people will say that it is. However, in past research examining the issue, the person pulling the switch has been a third party; that is, the puller was not directly involved in the situation, and didn’t stand to personally benefit or suffer because of the decision. But what would happen if the person pulling the switch was one of the hikers on one of the tracks; either on the side track (self-sacrifice) or the main track (self-saving)? Would it make a difference in terms of people’s moral judgments?

Well, the nonconsequentist account would say, “no; it shouldn’t matter”, because the behavior itself (redirecting a train onto a side track where it will kill one) remains constant; the welfare-maximizing consequentialist account would also say, “no; it shouldn’t matter”, because the welfare calculations haven’t changed (five live; one dies). However, this is not what we observe. When asked about how immoral it was for the puller to redirect the train, ratings were lowest in the self-sacrifice condition (M = 1.40/1.16 on a 1 to 5 scale in international and US samples, respectively), in the middle for the standard third-party context (M = 2.02/1.95), and highest in the self-saving condition (M = 2.52/2.10). In terms of whether or not it was morally acceptable to redirect the train, similar judgments cropped up: the percentage of US participants who said it was acceptable dropped as self-interested reasons began to enter into the question (the international sample wasn’t asked this question). In the self-sacrifice condition, these judgments of acceptability were highest (98%), followed by the third-party condition (84%), with the self-saving condition being the lowest (77%).

Participants also viewed the intentions of the pullers to be different, contingent on their location in this dilemma: specifically, the more one could benefit him or herself by pulling, the more people assumed that was the motivation for doing so (as compared with the puller’s motivations to help others: the more they could help themself, the less they were viewed as intending to help others). Now that might seem unsurprising: “of course people should be motivated to help themselves”, you might say. However, nothing in the dilemma itself spoke directly to the puller’s intentions. For instance, we could consider the case where a puller just happens to be saving their own life by redirecting the train away from others. From that act alone, we learn nothing about whether or not they would sacrifice their own life to save the lives of others. That is, one’s position in the self-beneficial context might simply be incidental; their primary motivation might have been to save the largest number of lives, and that just so happens to mean saving their own in the process. However, this was not the conclusion people seemed to be drawing.

*Side effects of saving yourself include increased moral condemnation.

Next, we examined a variant of the trolley dilemma that contained three tracks: again, there were five people on the main track and one person on each side track. As before, we varied who was pulling the switch: either the hiker on the main track (self-saving) or the hiker on the side track. However, we now varied what the options of the hiker on the side track were: specifically, he could direct the train away from the five on the main track, but either send the train towards or away from himself (the self-sacrifice and other-killing conditions, respectively). The intentions of the hiker on the side track, now, should have been disambiguated to some degree: if he intended to save the lives of others with no regard for his own, he would send the train towards himself; if he intended to save the lives of the hikers on the main track while not harming himself, he would send the train towards another individual. The intentions of the hiker on the main track, by contrast, should be just as ambiguous as before; we shouldn’t know whether that hiker would or would not sacrifice himself, given the chance.

What is particularly interesting about the results from this experiment is how closely the ratings of the self-saving and other-killing actors matched up. Whether in terms of how immoral it was to direct the train, whether the puller should be punished, how much they should be punished, or how much they intended to help themselves and others, ratings were similar across the board in both US and international samples. Even more curious is that the self-saving puller – the one whose intentions should be the most ambiguous – was typically rated as behaving more immorally and self-interestedly – not less – though this difference wasn’t often significant. Being in a position to benefit yourself from acting in this context seems to do people no favors in terms of escaping moral condemnation, even if alternative courses of actions aren’t available and the act is morally acceptable otherwise.

One final very interesting result of this experiment concerned the responses participants gave to the open-ended questions, “How many people [died/lived] because the lever was pulled?” On a factual level, these answers should be “1″ and “5″ respectively. However, our participants had a somewhat different sense of things. In the self-saving condition, 35% of the international sample and 12% of the US sample suggest that only 4 people were saved (in the other-killing condition, these percentages were 1% and 9%, and in the self-sacrifice condition they were 1.9% and 0%, respectively). Other people said 6 lives had been saved: 23% and 50% in the self-sacrifice condition, 1.7% and 36% in the self-saving condition, and 13% and 31% in the (international and US respectively). Finally, a minority of participants suggested that 0 people died because the train was redirected (13% and 11%), and these responses were almost exclusively found in the self-sacrifice conditions. These results suggest that our participants were treating the welfare of the puller in a distinct manner from the welfare of others in the dilemma. The consequences of acting, it would seem, were not judged to be equivalent across scenarios, even though the same number of people actually lived and died in each.

“Thanks to the guy who was hit by the train, no one had to die!”

In sum, the experiments seemed to demonstrate that these questions of morality are not to be limited to considerations of just actions and net consequences: to whom those consequences accrue seems to matter as well. Phrased more simply, in terms of moral judgments, the identity of actors seems to matter: my benefiting myself at someone else’s expense seems to have much different moral feel than someone else benefiting me by doing exactly the same thing. Additionally, the inferences we draw about why people did what they did – what their intentions were – appear to be strongly affected by whether that person is perceived to have benefited as a result of their actions. Importantly, this appears to be true regardless of whether that person even had any alternative courses of action available to them. That latter finding is particularly noteworthy, as it might imply that moral judgments are, at least occasionally, driving judgments of intentions, rather than the typically-assumed reverse (that intentions determine moral judgments). Now if only there was a humble and certainly not self-promoting psychologist who would propose some theory for figuring out how and why the identity of actors and victims tends to matter…

References: Marczyk, J. & Marks, M. (in press). Does it matter who pulls the switch? Perceptions of intentions in the trolley dilemma. Evolution and Human Behavior.