As a means of humble-bragging, I like to tell people that I have been rejected from many prestigious universities; the University of Pennsylvania, Harvard, and Yale are all on that list. Also on that list happens to be the University of New Mexico, home of one Geoffrey Miller. Very recently, Dr. Miller has found himself in a little bit of moral hot water from what seems to be an ill-conceived tweet. It reads as follows: “Dear obese PhD applicants: if you don’t have enough willpower to stop eating carbs, you won’t have the willpower to do a dissertation #truth“. Miller subsequently deleted the tweet and apologized for it in two follow up tweets. Now, as I mentioned, I’ve been previously rejected from Miller’s lab – on more than one occasion, mind you (I forgot if it was 3 or 4 times now) – so clearly, I was discriminated against. Indeed, discrimination policies are vital to anyone, university or otherwise, with open positions to fill. When you have 10 slots open and you get approximately 750 applications, you need some way of discriminating between them (and whatever method you use will disappoint approximately 740 of them). Evidently, being obese is one characteristic that people found to be morally unacceptable to even jokingly suggest you were discriminating on the basis of. This raises the question of why?

Let’s start with a related situation: it’s well-known that many universities make use of standardized test scores, such as the SAT or GRE, in order to screen out applicants. As a general rule, this doesn’t tend to cause too much moral outrage, though it does cause plenty of frustration. One could – any many do – argue that using these scores is not only morally acceptable, but appropriate, given that they predict some facets of performance at school-related tasks. While there might be some disagreement over whether or not the tests are good enough predictors of performance (or whether they’re predicting something conceptually important), there doesn’t appear to be much disagreement about whether or not they could be made use of, from a moral standpoint. That’s a good principle to start the discussion over the obese comment with, isn’t it? If you have a measure that’s predictive of some task-relevant skill, it’s OK to use it.

Well, not so fast. Let’s say, for the sake of this argument, that obesity was actually a predictor of graduate school performance. I don’t know if there’s actually any predictive value there, but let’s assume there is and, just for the sake of this example, let’s assume that being obese was indicative of doing slightly worse at school, like Geoffrey suggested; why it might have that effect is, for the moment, of no importance. So, given that obesity could, to some extent, predict graduate school performance, should schools be morally allowed to use it in order to discriminate between potential applicants?

I happen to think the matter is not nearly so simple as predictive value. For starters, there doesn’t seem to be any widely-agreed upon rule as for precisely how predictive some variable needs to be before its use is deemed morally acceptable. If obesity could, controlling for all other variables, predict an additional 1% of the variance graduate performance, should applications start including boxes for height and weight? While 1% might not seem like a lot, if you could give yourself a 1% better chance at succeeding at some task for free (landing a promotion, getting hired, avoiding being struck by a car or, in this case, admitting a productive student), it seems like almost everyone would be interested in doing so; ignoring or avoiding useful information would be a very curious route to opt for, as it only ensures that, on the whole, you make a worse decision than if you hadn’t considered it. One could play around with the numbers to try and find some threshold of acceptability, if they were so inclined (i.e. what if it could predict 10%, or only 0.1%), to help drive the point home. In any case, there are a number of different factors which could predict graduate school performance in different respects: previous GPAs, letters of recommendation, other reasoning tasks, previous work experience, and so on. However, to the best of my knowledge, no one is arguing that it would be immoral to only use any of them other than the best predictor (or the top X number of predictors, or the second best if you aren’t using the first, and so on). The core of the issue seems to center on obesity, rather than discriminant validity per se.

Thankfully, there is some research we can bring to bear on the matter. The research comes from a paper by Tetlock et al (2000) who were examining what they called “forbidden base rates” – an issue I touched on once before. In one study, Tetlock et al presented subjects with an insurance-related case: an insurance executive had been tasked with assessing how to charge people for insurance. Three towns had been classified as high-risk (10% chance of experiencing fires or break-ins), while another three had been classified as low-risk (less than 1% chance). Naturally, you would expect that anyone trying to maximize their risk-to-profit ratio would change different premiums, contingent on risk. If one is not allowed to do so, they’re left with the choices of offering coverage at a price that’s too low to be sustainable for them or too high to be viable for some of their customers. While you don’t want to charge low-risk people more than you need to, you also don’t want to under-charge the high-risk ones and risk losing money. Price discrimination in this example is a good thing.

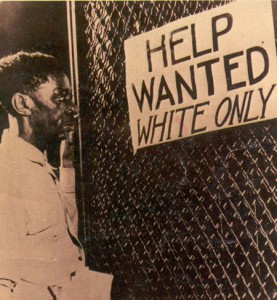

The twist was that these classifications of high- and low-risk either happened to correlate along racial lines, or they did not, despite their being no a priori interest in discriminating against any one race. When faced with this situation, something interesting happens: compared to conservatives and moderates, when confronted with data suggesting black people tended to live in the high-risk areas, liberals tended to advocate for disallowing the use of the data to make profit-maximizing economic choices. However, this effect was not present when the people being discriminated against in the high-risk area happened to be white.

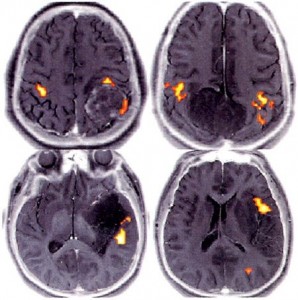

In other words, people don’t seem to have an issue with the idea of using useful data to discriminate amongst groups of people itself, but if that discrimination ended up affecting the “wrong” group, it can be deemed morally problematic. As Tetlock et al (2000) argued, people are viewing certain types of discrimination not as “tricky statistical issues” but rather as moral ones. The parallels to our initial example are apparent: even if discriminating on the basis of obesity could provide us with useful information, the act itself is not morally acceptable in some circles. Why people might view discrimination against obese people morally offensive itself is a separate matter. After all, as previously mentioned, people tend to have no moral problems with tests like GRE that discriminate not on weight, but other characteristics, such as working memory, information processing speeds, and a number of other difficult to change factors. Unfortunately, people tend to not have much in the way of conscious insight into how their moral judgments are arrived at and what variables they make use of (Hauser et al, 2007), so we can’t just ask people about their judgments and expect compelling answers.

Though I have no data bearing on the subject, I can make some educated guesses as to why obesity might have moral protection: first, and perhaps most obvious, is that people with the moral qualms about discrimination along the weight dimension might themselves tend to be fat or obese and would prefer to not have that count against them. In much the say way, I’m fairly confident that we could expect people who scored low on tests like the GRE to downplay their validity as a measure and suggest that schools really ought to be looking at other factors to determine admission criteria. Relatedly, one might also have people they consider to be their friends or family members who are obese, so they adopt moral stances against discrimination that would ultimately harm their social ingroup. If such groups become prominent enough, siding against them would become progressively costlier. Adopting a moral rule disallowing discrimination on the basis of weight can spread in those cases, even if enforcing that rule is personally costly, on account of not adopting the rule can end up being an even greater cost (as evidenced by Geoffrey currently being hit with a wave of moral condemnation for his remarks).

Hopefully it won’t crush you and drag you to your death. Hang ten.

As to one final matter, one could be left wondering why this moralization of judgments concern certain traits – like obesity – can be successful, whereas moralization of judgments based on other traits – like whatever GREs measure – doesn’t obtain. My guess in that regard is that some traits simply effect more people or effect them in much larger ways, and that can have some major effects on the value of an individual adopting certain moral rules. For instance, being obese effects many areas of one’s life, such as mating prospects and mobility, and weight cannot easily be hidden. On the other hand, something like GRE scores effect very little (really, only graduate school admissions), and are not readily observable. Accordingly, one manages to create a “better” victim of discrimination; one that is proportionately more in need of assistance and, because of that, more likely to reciprocate any given assistance in the future (all else being equal). Such a line of thought might well explain the aforementioned difference we see in judgments between racial discrimination being unacceptable when it predominately harms blacks, but fine when it predominately harmed whites. So long as the harm isn’t perceived as great enough to generate an appropriate amount of need, we can expect people to be relatively indifferent to it. It just doesn’t create the same social-investment potential in all cases.

References: Hauser, M., Cushman, F., Young, L., Kang-Xing Jin, R., & Mikhail, J. (2007). A dissociation between moral judgments and justifications. Mind & Language, 22, 1-21.

Tetlock, P., Kristel, O., Elson, S., Green, M., & Lerner, J. (2000). The psychology of the unthinkable: Taboo trade-offs, forbidden base rates, and heretical counterfactuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 (5), 853-870 DOI: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.5.853