“There is no such thing as “fake geek girls”; there are, only, girls who are at different, varying levels of falling in love with something that society generically considers to fall under the “nerd culture” category” -albinwonderland

About a month ago, Tony Harris (a comic book artist) posted a less-than-eloquently phrased rant about how he perceived certain populations within the geek subculture to be “fakes”; specifically, he targeted many female cosplayers (for a more put-together and related train of thought, see here). Predictably, reactions were had and aspersions were cast. Though I have barely dipped my toes into this particular controversy, the foundations of it are hardly new. This experience – the tensions between the “elites” and “fakes” – is immediately relatable to all people, no matter how big of a fish they happen to be in the various social ponds they inhabit. While the specific informal rules of subcultures (how one should dress, what one may or may not be allowed to like, and so on) may differ from group to group, these superficial differences dissolve into the background when considering the underlying similarities of their logic; nerd culture will just be our guide to it at present.

“NERRRRRRDS!”

“NERRRRRRDS!”

I get the sense that, because the issue involved gender, a good deal of the collective cognitive work that went into this debate focused on generating and defending against claims of sexism, which, while an interesting topic in its own right, I find largely unproductive for my current purposes. In the interests of examining the underlying issues without the baggage that gender brings, I’d like to start by answering a seemingly unrelated question: why might Maddox feel that bacon has been “ruined” for him by its surge in popularity?

The Internet needs to collectively stop sucking Neil deGrasse Tyson’s dick. And add bacon and zombies to that list. I love bacon, but fuck you for ruining it, everyone. Holy shit, just shut the fuck up about bacon. Yeah, it’s great, we know. Bacon cups, bacon salt, bacon shirts, bacon gum, bacon, bacon, bacon, WE GET IT. Bacon is your Jesus, we know, now do a shot of bleach and take some buckshot to the face.

This comment likely seems strange (if also a bit relatable) to many people: why should anyone else’s preferences influence Maddox’s? If I like chocolate ice cream, it would indeed be odd if I started liking it less if I was around other people who also seemed to like it, especially if the objective properties of the ice cream in question haven’t changed; it’s still the same ice cream (or bacon) that was there a moment ago. It seems clear from that consideration that bacon per se isn’t what Maddox feels has been ruined. What Maddox doesn’t seem to like is that other people like it; too many other people, however many that works out to be. So now that we’ve honed the question somewhat (why doesn’t Maddox like that other people like bacon?), let’s turn to Dr. Seuss to, at least partially, answer it.

In Dr. Seuss’s story, The Sneetches, we find an imaginary population of anthropomorphic birds, some of which have a star on their belly and others of which do not. The Sneetches form group memberships along these lines, with the stars – or lack thereof – serving as signals for which group any given Sneetch belongs to. Knowing whether or not a Sneetch had a star could, in this world, provide you with useful information about that individual: where might this Sneetch stand socially, relative to its peers; who might this Sneetch tend to associate with; what kind of resources might this Sneetch have access to. However, when a man rolls into town and starts to affix stars to the bellies of the starless Sneetches, this system gets thrown out of order. The special status of the initially-starred Sneetches is now questioned, because every Sneetch is sending an identical signal, meaning that signal can no longer provide any useful information. The initially-starred Sneetches then, apparently feeling that the others have “ruined” stars for them, subsequently remove their stars in an attempt to restore the signal value and everyone eventually learns something about racism. In this example, though, it becomes readily apparently why preferences for having stars changed: it was the signal value of the stars – the information they conveyed – that changed, not the stars themselves, and this information is, or rather, was, a valuable resource.

The key insight here is that if an individual is trying to signal some unique quality about itself, it does them no good to try and achieve that goal through a non-unique or easy-to-fake signal. Any benefits that the signal can bring will soon be driven to non-existence if other organisms are free to start sending that same signal. So let’s apply that lesson back to bacon question: Maddox is likely bothered by too many other people liking bacon because, to some extent, it means the signal strength of his liking bacon has been degraded. As part of Maddox’s affinity for bacon seemed to extend beyond its physical properties, some part of his affinity for the product was lost with that signal value; it no longer said much about him as a person. You’ll notice that I’ve forgone the question of what precisely Maddox might have been trying to signal by advertising his love of bacon. I’ve done this because, while it might be an interesting matter in its own right, it’s entirely beside the point. Regardless of what the signal is supposed to be about, ubiquitousness will always threaten it.

While many might be tempted to take this point as a strike against the elitists (“they don’t really like what they say they like; they only like what liking those things says about them”, would resemble how that might get phrased), it’s important to bear in mind that this phenomenon is not restricted to the elites. As Maddox suggests in his post, many of the people whom he deems to be “fake” nerds are attempting to make use of that signal value themselves, despite lacking the trait that the signal is supposed to advertise:

People love science in the same way they love classical music or art. Science and “geeky” subjects are perceived as being hip, cool and intellectual. So people take a passing interest just long enough to glom unto these labels and call themselves “geeks” or “nerds” every chance they get.

Like the starless Sneetches, these counterfeiters are trying to gain some benefit (in this case, perhaps the perception that they’re intelligent or interesting) through a dishonest means (by not being either of those things, but still telling people they are). This poses a very real social problem for signalers to overcome: how to ensure that (their) communication is (perceived as being) honest so the value of the communication can be maintained (for them)? If I can send a signal that advertises some latent quality about myself, I can potentially gain some benefit by doing so. However, if people who do not have that underlying quality also start sending the signal, they can reap those same benefits at my expense. The resources in question here are zero-sum, so more of those resources going to others means less for me, and vice versa. This means it’s in my interests to send signals that others cannot send in order to better monopolize those benefits, and to likewise strive to give receivers the impression that my signal is of a greater value than the signals of others.

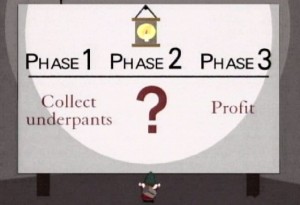

Despite being beset by possible deception from senders, it is also in the interests of those receiving the signals that said signals remain honest. Resources, social or otherwise, that I invest in one individual cannot also be invested in another. Accordingly, when deciding how to allocate that limited investment budget, it’s in my interests to do so on the basis of good information; information which I would no longer have access to as the signal value degrades. Appreciating this problem helps answer a question posed by BlackNerdComedy: why does he remember information about an obscure cartoon called “SpaceCats”? More generally, he wonders aloud why people get “challenged” on their gamer credibility on the basis of their obscure knowledge and what purpose such challenges might serve (ironically, he also has another video where he complains about how some nerds consider others to not be “real nerds”, and then goes on to say that the people judging others for not being “real nerds” are, themselves, not “real nerds” because of it). In the light of the communication problem, the function of these challenges seems to become clear: they’re attempts at assessing honesty. Good information about someone’s latent qualities simply cannot be well-assessed by superficial knowledge. In much the same way, the depths of one’s math abilities can’t be well-assessed by testing on basic addition and subtraction alone; testing on the basics simply doesn’t provide much useful information, especially if the basics are widely known. If you start giving people calculus problems to do instead, you now have a better gauge for relative math abilities.

Obscure knowledge is no the only means through which one can try and guarantee the honesty of the signal, however. Another point that has frequently been raised in this debate involves people talk about “paying your dues” in the community, or suffering because of one’s nerdy inclinations. As Maddox puts it:

Well someone forgot to give the “nerds-are-sexy” memo to my friends, because most of them are nerds and none of them are getting laid. Here’s a quick rule of thumb: if you don’t have to make an effort to get laid, you’re not a nerd.…Being a nerd is a byproduct of losing yourself in what you do, often at the expense of friends, family and hygiene. Until or unless you’ve paid your dues, you aren’t welcome.

For starters, the emphasis on costs is enlightening: paying costs helps ensure the signal is harder to fake (Zahavi, 1975), and the greater those costs, the more likely the signal is honest. If someone is socially ridiculed for their hobby, it’s a fairly good sign that they aren’t doing it just to be popular, as this would be rather counterproductive. Maddox’s comment also taps into the distinction that Tooby and Cosmides (1996) made in regards to “genuine” and “fair-weather” friends: genuine friends have a deep interest in your well-being, making them far less likely to abandon you when the goings get tough. By contrast, fair-weather friends stick around only so long as your deliver them the proper benefits, but will be more likely to turn on you or disappear when you become too costly. Again, people are faced with the problem of discriminating one type from the other in the face of less-than-honest communication. Just because someone tells you they deeply value your friendship, it doesn’t mean that they have your best interests at heart. This requires people to make use of other cues in assessing the social commitments of others and, it seems, one good way of doing this involves looking for people who literally have no other social prospects. If one has been rejected by all other social groups except the nerd community, they will be less likely to abandon that community because they have no better alternative. By contrast, those who are deemed to have plenty of viable social alternatives (such as physically attractive people) can be met with a greater degree of skepticism; they have other avenues they could take if the going gets too rough, which might suggest their social commitment is not as strong as it could otherwise be.

His loyalty to the nerd community is the only strong thing about him.

This is only a general sketch of the some of the issues at play in this debate; the specifics can get substantially more complicated. For instance, the goal of a signaler, as mentioned before, is to beat out other signalers, and this can involve a good deal of dishonesty in the signaler’s representations of other signalers. It’s worth bearing in mind that all signalers, whether they’re “real” or “fake”, have this same vested interest: beating the other signalers. Being honest is only one way of potentially doing that. There’s also the matter of social value, in that even if a signaler is sending a completely honest signal about their latent qualities and commitments, they might, for other reasons, simply not be very good social investments to most people, even within the community. As I said, it gets complicated, and because the majority of these calculations seem to be made without any conscious awareness, the subject gets even trickier to untangle.

One final point of the debate that caught my eye was the solution that people from either side of the debate appear to agree on (at least to some extent) for dealing with the problem: people should stop trying to label themselves as “gamers” or “nerds” altogether and simply enjoy their hobbies. In the language of the underlying theory, people can free themselves from harassment (from within the community, anyway) if they stop trying to signal something about themselves to others, and, by proxy, stop competing for whatever resources at are stake, through their hobbies. The problem with this suggestion is two-fold: (a) the resources at stake here are valuable, so it’s unlikely that competition for them will stop, and (b) most people don’t consciously recognize they’re competing in the first place; in fact, most people would explicitly deny such an implication. After all, if one is trying to maintain the perception they’re honestly saying something about themselves, it would do them no favors to acknowledge any ulterior motives, as this acknowledgement would tend to degrade the value of their signals on its own. It would degrade them, that is, unless one is trying to signal they’re more conscious of their own biases than other people, and a good social partner because of it…

References: Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1996). Friendship and the banker’s paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. Proceedings of The British Academy, 88, 119-143

Zahavi, A. (1975). Mate selection—A selection for a handicap Journal of Theoretical Biology, 53 (1), 205-214 DOI: 10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3