In my last post dealing with PZ Myer’s praise for the adaptationist paradigm, which was confusingly dressed up as criticism, PZ suggested the following hypothesis about variation in nose shape:

Most of the obvious phenotypic variation we see in people, for instance, is not a product of selection: your nose does not have the shape it does, which differs from my nose, which differs from Barack Obama’s nose, which differs from George Takei’s nose, because we independently descend from populations which had intensely differing patterns of natural and sexual selection for nose shape; no, what we’re seeing are chance variations amplified in frequency by drift in different populations.

Today’s post will be a follow-up on this point. Now, as I said before, I currently have no strong hypotheses about what past selection pressures (or lack thereof) might have been at work shaping the phenotypic variation found in noses; noses which differ in shape and size noticeably from chimps, gorillas. orangutans, and bonobos. The cross-species consideration, of course, is a separate matter from phenotypic variation within our species, but these comparisons might at least make one wonder why the human nose might look the way it does compared to other apes. If that reason(s) could be discerned, it might also tell us something about current types of variation we see in modern human populations. The reason why noses vary between species might indeed be “genetic drift” or “developmental constraint” rather than “selection”, just as the answer to within-species variation of that trait might be as well. Before simply accepting those conclusions as “obviously true” on the basis of intuition alone, though, it might do us some good to give them a deeper consideration.

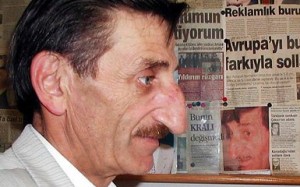

“Follow your nose; it always knows! Alternatively, following evidence can work too!”

One of the concerns I raised about PZ’s hypothesis is that it does not immediately appear to make anything resembling a novel or useful prediction. This concern itself is far from new, with a similar (and more eloquently stated) point being raised by Tooby and Cosmides in 1997 [H/T to one of the commenters for providing the link]:

Modern selectionist theories are used to generate rich and specific prior predictions about new design features and mechanisms that no one would have thought to look in the absence of these theories, which is why they appeal so strongly to the empirically minded….It is exactly this issue of predictive utility, and not “dogma”, that leads adaptationists to use selectionist theories more often than they do Gould’s favorites, such as drift and historical contingency. We are embarrassed to be forced, Gould-style, to state such a palpably obvious thing, but random walks and historical contingency do not, for the most part, make tight or useful prior predictions about the unknown design features of any single species.

That’s not to say that one could not, in principle, derive a useful or novel prediction from the drift hypothesis; just that one doesn’t immediate jump out at me in this case, nor does PZ explicitly mention any specific predictions he had in mind. Without any specific predictions, PZ’s suggestion about variation in nose shape, while it may well be true to some small or large degree (given that PZ’s language chalks most to all of variation up to drift, rather than selection; it’s unclear precisely what proportion he had in mind), his claim also runs the risk of falling prey to the label of “just-so story“.

Since PZ appears to be really concerned that evolutionary psychologists do not make use of drift in their research as often as he’d like, this, it seems, would have been the perfect opportunity for him to show us how things ought to be done: he could have derived a number of useful and novel predictions from the drift hypothesis and/or shown how drift might better account for some aspects of the data in nose variation that he had in mind, relative to other current competing adaptationist theories on nose variation. I’m not even that particular about the topic of noses, really; PZ might prefer to examine a psychological phenomenon instead, as this is evolutionary psychology he’s aiming his criticisms at. This isn’t just a mindless swipe at PZ’s apparent lack of a testable hypothesis either: as long as his predictions derived from a drift hypothesis lead to some interesting research, that would be a welcome addition to any field.

Let’s move on from the prediction point towards the matter of whether selection played a role in determining current nose variation. In this area, there is another concern of mine about the drift hypothesis that reaches beyond the pragmatic one. As PZ mentions in his post, selection pressures are generally “blind” to very small fitness benefits or detriments. If your nose differs in size from mine by 1/10 of a millimeter, that probably won’t have much of an effect on eventual fitness outcomes, so that variation might stick around in the next generation relatively unperturbed. The next generation will, in turn, introduce new variation into the population due to sexual recombination and mutation. If the average difference in nose shape was 1/10 of a millimeter in the previous generation, that difference may now grow to, say, 2/10th of a millimeter. Since that difference still isn’t likely enough to make much of a difference, it sticks around into the next generation, which introduces new variation that isn’t selected for or against, and so on. These growths in average variation, while insignificant when considered in isolation, can begin to become the target of selection as they accumulate and their fitness costs and benefits begin to become non-negligible. In this hypothetical example, nose shape and size might begin to become the target of stabilizing selection where the more extreme variations are weeded out of the population, perhaps because they’re viewed as less sexually appealing or become less functional than other, less extreme variants (the factors that PZ singled out as not being important).

So let’s say one was to apply an adaptationist research paradigm to nose variation and compare it to PZ’s drift hypothesis (falsely assuming, for the moment, that an adaptationist research paradigm is in some way supposed to be opposed to a drift one). A researcher might begin by wondering what functions nose shape could have. Note that these need not be definitive conclusions; merely plausible alternatives. Once our researcher has generated some possible functions, they would begin to figure out ways of testing these candidate alternatives. Noback et al (2011), for instance, postulated that the nasal cavity might function, in part, to warm and humidify incoming air before it reaches the lungs and, accordingly, predicted that nasal cavities ought to be expected to vary contingent on the requirements of warming and humidifying across varying climates.

This adaptationist research paradigm generated six novel predictions, which is a good start compared to PZ’s zero. Noback et al (2011) then tested test predictions against 100 skulls from 10 different populations spanning 5 different climates. The resulted indicated significant correlations between nearly every climate factor (temperature and humidity) and nasal cavity shape. Further, the authors managed to disconfirm more than one of their initial hypotheses, and were also able to suggest that these variations in nasal cavity shape were not due solely to allometric effects. They also mention plenty of variation is left unexplained, and some variation in nasal cavity variation might also be due to tradeoffs between warming and humidifying incoming air and functions of the nose (such as olfaction).

So, just to recap, this adaptationist research concerning nose variation yielded a number of testable predictions (it’s useful), found evidence consistent with them in some cases but not others (it’s falsifiable), tested alternative explanations (variation not solely due to allometry), mentioned tradeoffs between functions, and left plenty of variation unexplained (did not assume every feature was an adaptation). This is compared to PZ’s drift hypothesis, which made no explicit predictions, cited no data, made no mention of function (presumably because it would postulate there isn’t one), and would seem to not be able to account well for this pattern of results. Perhaps PZ might note this research deals primarily with internal features of the nose; not external ones, and the external features are what he had mind when he proposed the drift hypothesis. As he’s not explicit about which parts of nose shape were supposed to be under discussion, it’s hard to say whether he feels results like these would pose any problems for his drift hypothesis.

While I still remain agnostic about the precise degree to which variation in nose shape has been the target of selection, as I’m by no means an expert on the subject, the larger point here is how useful adaptationist research can be. It’s not enough to just declare that variation in a trait is obviously the product of drift and not selection and leave it at that in much the same way that one can’t just assume a trait in an adaptation. As far as I see it, neither drift nor adaptation ought to be the null hypothesis in this case. Predictions need to be developed and tested against the available data, and the adaptationist paradigm is very helpful in generating those predictions and figuring out what data might be worth testing. That’s most certainly not to say those predictions will always be right, or that the research flowing from someone using that framework will always be good. The point is just that adaptationism itself is not the problem PZ seems to think it is.

References: Noback, M., Harvati, K., & Spoor, F. (2011). Climate-related variation of the human nasal cavity American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 145 (4), 599-614 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.21523

Pingback: Evopsychopathy 4: Adaptive scenarios | Evolving Thoughts

Pingback: Is It Only “Good” Science When It Confirms Your World View? | Pop Psychology