This is going to be something of a back to basics post, but a necessary one. Necessary, that is, if the comments I’ve been seeing lately are indicative of the thought processes of the population at large. It would seem that many people make a fundamental error when thinking about evolutionary explanations for behavior. The error involves thinking about the ultimate function of an adaptation or the selection pressures responsible for its existence, rather than the adaptation’s input conditions, in considering whether said adaptation is responsible for generating some proximate behavior. (If that sounded confusing, don’t worry; it’ll get cleared up in a moment) While I have seen the error made frequently among various lay people, it appears to even be common among those with some exposure to evolutionary psychology; out of the ninety undergraduate exams I just finished grading, only five students got the correct answer to a question dealing with the subject. That is somewhat concerning.

I hope that hook up was worth the three points it cost you on the test because you weren’t paying attention.

Here’s the question that the students were posed with:

People traveling through towns that they will never visit again nonetheless give tips to waiters and taxi drivers. Some have claimed that the theory of reciprocal altruism seems unable to explain this phenomenon because people will never be able to recoup the cost of the tip in a subsequent transaction with the waiter or the driver. Briefly explain the theory of reciprocal altruism, and indicate whether you think that this theory can or cannot explain this behavior. If you say it can, say why. If you say it cannot, provide a different explanation for this behavior.

The answers I received suggested that the students really did understand the function of reciprocal altruism: they were able to explain the theory itself, as well as some of the adaptive problems that needed to be solved in order for the behavior to be selected for, such as the ability to remember individuals and detect cheaters. So far, so good. However, almost all the students then indicated that the theory could not explain tipping behavior, since there was no chance that the tip could ever be reciprocated in the future. In other words, tipping in that context was not adaptive, so adaptations designed for reciprocal altruism could not be responsible for the behavior. The logic here is, of course, incorrect.

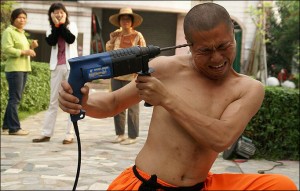

To understand why that answer is incorrect, let’s rephrase the question, but this time, instead of tipping strangers, let’s consider two people having sex:

People who do not want to have children still wish to have sex, so they engage in intercourse while using contraceptives. Some have claimed that the theory of sexual reproduction seems unable to explain this phenomenon because people will never be able to reproduce by having sex under those conditions. Briefly explain the theory of sexual reproduction, and indicate whether you think that this theory can or cannot explain this behavior. If you say it can, say why. If you say it cannot, provide a different explanation for this behavior.

No doubt, there are still many people who would get this question wrong as well; they might even suggest that the ultimate function of sex is just to “feel pleasure”, not reproduction, because feeling pleasure – in and of itself – is somehow adaptive (Conley, 2011, demonstrating that this error also extends to published literature). Hopefully, however, for most people at least one error should now appear a little clearer: contraceptives are an environmental novelty, and our psychology is not evolved to deal with a world in which they exist. Without contraceptives, the desire to have children is irrelevant to whether or not some sexual act will result in pregnancy.

That desire is also irrelevant if you’re in the placebo group

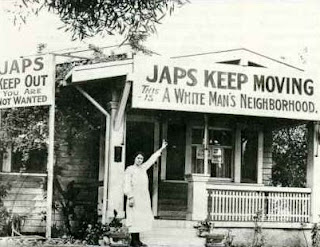

Contraceptives are a lot like taxi drivers, in that both are environmental novelties. Encountering strangers that you were not liable to interact with again was probably the exception, rather than the rule, for most of human evolution. That said, even if contraceptives were taken out of the picture and our environment was as “natural” as possible, our psychology would still not be perfectly designed for each and every context we find ourselves in. Another example about sex easily demonstrates this point: a man and a woman only need to have sex once, in principle, to achieve conception. Additional copulations before or beyond that point are, essentially, wasted energy that could have been spent doing other things. I would wager, however, that for each successful pregnancy, most couples probably have sex dozens or hundreds of times. Whether because the woman is not and will not be ovulating, because one partner is infertile, or because the woman is currently pregnant or breastfeeding, there are plenty of reasons why intercourse does not always lead to conception. In fact, intercourse itself would probably not be adaptive in the vast majority of occurrences, despite it being the sole path to human reproduction (before the advent of IVF, of course).

Turning the focus back to reciprocal altruism, throughout their lives, people behave altruistically towards a great many people. In some cases, that altruism will be returned in such a way that the benefits received will outweigh the initial costs of the altruistic act; in other cases, that altruism will not be returned. What’s important to bear in mind is that the output of some module adapted for reciprocal altruism will not always be adaptive. The same holds for the output of any psychological module, since organisms aren’t fitness maximizers – they’re adaptation executioners. Adaptations that tended to increase reproductive success in the aggregate were selected for, even if they weren’t always successful. These sound like basic points (because they are), but they’re also points that tend to frequently trip people up, even if those people are at least somewhat familiar with all the basic concepts themselves. I can’t help but wonder if that mistake is made somewhat selectively, contingent on topic, but that’s a project for another day.

References: Conley, T. (2011). Perceived proposer personality characteristics and gender differences in acceptance of casual sex offers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100 (2), 309-329 DOI: 10.1037/a0022152