Like me, most of you probably come from the streets. On the streets, it’s common knowledge that “daddy issues” are the root cause of women developing interests in several activities. Daddy issues are believed to play a major role in becoming a stripper, developing a taste for bad boys, and getting a series of tattoos containing butterflies, skulls, and/or quotes with at least one glaring spelling mistake. As pointed out by almost any group in the minority at one point or another, however, that knowledge is common does not imply it is also correct. For instance, I’ve recently learned that drive-bys are not a legitimate form of settling academic disagreements (or at least that’s what I’ve been told; I still think it made me the winner of that little debate). So, enterprising psychologist that I am, I’ve decided to question the following piece of folk wisdom: is father absence really a causal variable in determining a young girl’s life history strategy, specifically with regard to the onset of menstruation?

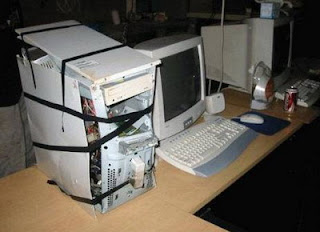

Watch carefully now; that young boy may start to menstruate at any moment… wait; which study is this?

First, a little background is order. Life history theory deals with the way an organism allocates its limited resources in an attempt to maximize its reproductive potential. Using resources to develop one trait precludes the use of those same resources for developing other traits, so there are always inherent trade-offs that organisms need to make during development. Different species have stumbled upon different answers as to how these trade-offs should be made: is it better to be small or large? Is it better to start reproducing as soon as possible or start reproducing later? Is it better to produce many offspring and invest little in each, or produce fewer offspring and invest more? These developmental and behavioral trade-offs all need to be made under a series of ecological constraints, such as the availability of resources or the likelihood of survival. For instance, it makes no sense for a convict to refuse a final cigarette before a firing squad executes him out of concerns for his health. There’s no point worrying about tomorrow if there won’t be one. On the other hand, if you have a secure future, maybe Russian roulette isn’t the best choice for a past time.

So where do family-related issues enter into the equation? Within each species, different individuals have slightly different answers for those developmental question, and those answers are not fixed from conception. Like all traits, their expression is contingent on the interaction between genes and the environment those genes find themselves in. A human child that finds itself with severely limited access to relevant resources is thus expected to alter their developmental trajectory according to their constraints. This has been demonstrated to be the case for obvious variables like obtaining adequate nutrition: if a young girl does not have access to enough calories, her sexual maturation will be delayed, as her body would be unlikely to successfully support the required investment a child brings.

Another of these hypothesized resources is paternal investment. The suggestion put forth by some researchers (Ellis, 2004) is that a father’s presence or absence signals some useful information to daughters regarding the availability of future mating prospects. The theory that purports to explain this association states that when young girls experience a lack of paternal investment, their developmental path shifts towards one that expects future investment by male partners to be lacking and not vital to reproduction. This, in turn, results in more sexual precociousness. Basically, if dad wasn’t there for you growing up, then, according to this theory, other men probably won’t be either, so it’s better to not develop in a way that expects future investment. That father absence has been associated with a slightly earlier onset of menarche (first menstruation) in women has been taken as evidence supporting this theory.

The major problem with this suggestion is that no causal link has been demonstrated. The only thing that has been demonstrated is that father absence tends to correlate with an earlier age of menstruation, and the degree to which the two are correlated is rather small. According to some correlations reported by Ellis (2004), it looks as if one could predict between 1 to 4% of the variance in timing of pubertal development on the basis of father absence, depending on which parts of the sample is under discussion. Further, that already small correlation does not control for a wide swath of additional variables, such as almost any variables that are found outside the home environments. This entire social world that exists outside of a child’s family has been known to have been of some (major) importance in children’s development, while the research on the home environment seems to suggest that family environments and parenting styles don’t leave lasting marks on personality (Harris, 1998).

As the idea that outside the home environments matter a lot has been around for over a decade, it would seem the only sane things for researchers to do are more nearly identical studies, looking at basically the same parenting/home variables, and finding the same, very small to no effect, then making some lukewarm claim about how it might be causation, but then again might not be. This pattern of research is about as tedious as that last sentence is long, and it plagues psychological research in my opinion. In any case, towards achieving that worthwhile goal of breaking through some metaphorical brick wall by just running into it enough times, Tither and Ellis (2008) set out to examine whether the already small correlation between daughter’s development and father presence was due to a genetic confound.

To do this, Tither and Ellis examined sister-pairs that contained both an older and younger sister. The thinking here is that it’s (relatively) controlled for on a genetic level, but younger sisters would experience more years of father absence following the break-up of a marriage, relative to the older sisters, which would in turn accelerate sexual maturation of the younger one. Skipping to the conclusions, this effect was indeed found, with younger sisters reporting earlier menarche than older sisters in father absent homes (accounting for roughly 2% of the variance). Among those father absent homes, this effect was carried predominately by fathers with a high reported degree of anti-social, dysfunctional behavior, like drug use and suicide attempts (accounting for roughly 10% of the variance within this subset). The moral seems to be that “good-enough” fathers had no real effect, but seriously awful parenting on the father’s part, if experienced at a certain time in a daughter’s life, has some predictive value.

So you may want to hold off on your drug-fueled rampages until your daughter’s about eight or nine years old.

First, let me point out the rather major problem here on a theoretical level. If the theory here is that father presence or absence sends a reliable signal to daughters about the likelihood of future male investment, then one would expect that signal to at least be relatively uniform within a family. If the same father is capable of signaling to an older daughter that future male investment is likely, and also signaling to a younger daughter that future male investment isn’t likely, then that signal would hardly be reliable enough for selection to have seized on.

Second, while I agree with Tither and Ellis that these results are consistent with a casual account, they do not demonstrate that the father’s behavior was the causal variable in any way whatsoever. For one thing, Ellis (2004) notes that this effect of father presence vs absence doesn’t seem to exist in African American samples. Are we to assume that father presence or absence has only been used as a signal by girls in certain parts of the world? Further, as the authors note, there tend to be other changes that go along with divorce and paternal psychotic behavior that will have an effect on a child’s life outside of the home. To continue and beat what should be a long dead horse, researchers may want to actually start to look at variables outside of the family to account for more variation in a girl’s development. After all, it’s not the family life that a daughter is maturing sexually for; it’s her life with non-family members that’s of importance.

References: Ellis, B.J. (2004). Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 920-958

Harris, J.R. (1998). The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out The Way They Do. New York: Free Press

Tither, J.M., & Ellis, B.J. (2008). Impact of fathers on daughters’ age at menarche: A genetically and environmentally controlled sibling study. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1409-1420/