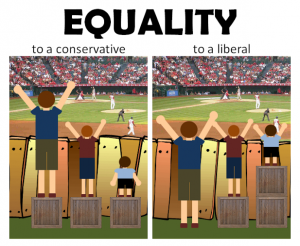

“We may now state the minimum conception: Morality is, at the very least, the effort to guide one’s conduct by reason…while giving equal weight to the interests of each individual affected by one’s decision” (emphasis mine).

The above quote comes to us from Rachaels & Rachaels (2010) introductory chapter entitled “What is morality?” It is readily apparent that their account of what morality is happens to be a conscience-centric one, focusing on self-regulatory behaviors (i.e. what you, personally, ought to do). These conscience-based accounts are exceedingly popular among many people, academics and non-academics alike, perhaps owing to its intuitive appeal: it certainly feels like we don’t do certain things because they feel morally wrong, so understanding morality through conscience seems like the natural starting point. With all due respect to the philosopher pair and the intuitions of people everywhere, they seem to have begun their analysis of morality on entirely the wrong foot.

Now, without a doubt, understanding conscience can help us more fully understand morality, and no account of morality would be complete without explaining conscience; it’s just not an ideal starting point for beginning our analysis (DeScioli & Kurzban, 2009; 2013). This is because moral conscience does not, in and of itself, explain our moral intuitions well. Specifically, it fails to highlight the difference between what we might consider ‘preferences’ and ‘moral rules’. To better understand this distinction, consider two following statements: (1) “I have no interest in having homosexual intercourse”, and (2) “Homosexual intercourse is immoral”. These two statements are distinct utterances, aimed at expressing different thoughts. The first expresses a preference, and that preference would appear sufficient for guiding one’s behavior, all else being equal; the latter statement, however, appears to express a different sentiment altogether. That second sentiment appears to imply that others ought to not have homosexual intercourse, regardless of whether you (or they) want to engage in the act.

This is the key distinction, then: moral conscience (regulating one’s own behavior) does not appear to straightforwardly explain moral condemnation (regulating the behavior of others). Despite this, almost every expressed moral rule or law involves punishing others for how they behave – at least implicitly. While the specifics of what gets punished and how much punishment is warranted vary to some degree from individual to individual, the general form of moral rules does not. Were I to say I do not wish to have homosexual intercourse, I’m only expressing a preference, a bit like stating whether or not I would like my sandwich on white or wheat bread. Were I to say homosexuality is immoral, I’m expressing the idea that those who engage in the act ought to be condemned for doing so. By contrast, I would not be interested in punishing people for making the ‘wrong’ choice about bread, even if I think they could have made a better choice.

While we cannot necessarily learn much about moral condemnation via moral conscience, the reverse is not true: we can understand moral conscience quite well through moral condemnation. Provided that there are groups of people who will tend to punish for you for doing something, this provides ample motivation to avoid engaging in that act, even if you otherwise highly desire to do so. Murder is a simple example here: there tend to be some benefits for removing specific conspecifics from one’s world. Whether because those others inflict costs on you or prevent the acquisition of benefits, there is little question that murder might occasionally be adaptive. If, however, the would-be target of your homicidal intentions happens to have friends and family members that would rather not see them dead, thank you very much, the potential costs those allies might inflict need to be taken into account. Provided those costs are appreciably great, and certain actions are punished with sufficient frequency over time, a system for representing those condemned behaviors and their potential costs – so as to avoid engaging in them – could easily evolve.

“Upon further consideration, maybe I was wrong about trying to kill your mom…”

That is likely what our moral conscience represents. To the extent that behaviors like stealing from or physically harming others tended to be condemned and punished, we ought to be expected to have a cognitive system to represent that fact. Now perhaps that all seems a bit perverse. After all, many of us simply experience the sensation that an act is morally wrong or not; we don’t necessarily think about our actions in terms of the likelihood and severity of punishment (we do think such things some of the time, but that’s typically not what appears to be responsible for our feeling of “that’s morally wrong”. People think things are morally wrong regardless of whether one is caught doing it). That all may be true enough, but remember, the point is to explain why we experience those feelings of moral wrongness; not to just note that we do experience them and that they seem to have some effect on our behavior. While our behavior might be proximately motivated by those feelings of moral wrongness, those feelings came to exist because they were useful in guiding out behavior in the face of punishment. That does raise a rather important question, though: why do we still feel certain acts are immoral even when the probability of detection or punishment are rather close to zero?

There are two ways of answering that question, neither of which is mutually exclusive with the other. The first is that the cognitive systems which compute things like the probability of being detected and estimate the likely punishment that will ensue are always working under conditions of uncertainty. Because of this uncertainty, it is inevitable that the system will, on occasion, make mistakes: sometimes one could get away without repercussions when behaving immorally, and one would be better off if they took those chances than if they did not. One also needs to consider the reverse error as well, though: if you assess that you will not be caught or punished when you actually will, you would have been better off not behaving immorally. Provided the costs of punishment are sufficiently high (the loss of social allies, abandonment by sexual partners, the potential loss of your life, etc), it might pay in some situations to still avoid behaving in morally unacceptable ways even when you’re almost positive you could get away with it (Delton et al, 2012). The point here is that it doesn’t just matter if you’re right or wrong about whether you’re likely to be punished: the costs to making each mistake need to be factored into the cognitive equation as well, and those costs are often asymmetric.

The second way of approaching that question is to suggest that the conscience system is just one cognitive system among many, and these systems don’t always need to agree with one another. That is, a conscience system might still represent an act as morally unacceptable while other systems (those designed to get certain benefits and assess costs) might output an incompatible behavioral choice (i.e. cheating on your committed partner despite knowing that it is morally condemned to do so, as the potential benefits are perceived as being greater than the costs). To the extent that these systems are independent, then, it is possible for each to hold opposing representations about what to do at the same time. Examples of this happening in other domains are not hard to find: the checkerboard illusion, for instance, allows us to hold both the representation that A and B are different colors and that A and B are the same color in our mind at once. We need not be of one mind about all such matters because our mind is not one thing.

Now, to be sure, there are plenty of instances where people will behave in ways deemed to be immoral by others (or even by themselves, at different times) without feeling the slightest sensation of their conscience telling them “what you’re doing is wrong”. Understanding how the conscience develops, and the various input conditions likely to trigger it – or fail to do so – are interesting matters. In order to make better progress on researching them, however, it would benefit researchers to begin with an understanding of why moral conscience exists. Once the function of conscience – avoiding condemnation – has been determined, figuring out what questions to ask about conscience becomes an altogether easier task. We might expect, for instance, that moral conscience is less likely to be triggered when others (the target and their allies) are perceived to be incapable of effective retaliation. While such a prediction might appear eminently sensible when beginning with condemnation, it is not entirely clear how one could deliver such a prediction if they began their analysis with conscience instead.

References: Delton, A., Krasnow, M., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2012). Evolution of direct reciprocity under uncertainty can explain human generosity in one-shot encounters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 13335-13340.

DeScioli P, & Kurzban R (2009). Mysteries of morality. Cognition, 112 (2), 281-99 PMID: 19505683

DeScioli P, & Kurzban R (2013). A solution to the mysteries of morality. Psychological bulletin, 139 (2), 477-96 PMID: 22747563

Rachaels, J. & Rachels S. (2010). The Elements of Moral Philosophy. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.