“If a wife left her husband with three kids and no job/ to run off to fuck in Hawaii with some doctor named Bob/ you could skin them and drain them of blood so they die…especially Bob. Then you would be justice guy”. – Stephen Lynch, “Superhero”

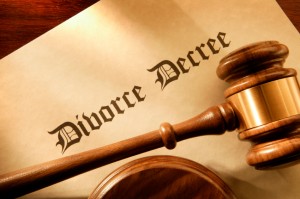

For those of you not in the know, Stephen Lynch is a popular comedic musician. In the song, “Superhero”, Stephen gives the above description of what he would do were he “Justice Guy”. As one can gather, in this story, Stephen’s wife has run off with another man, resulting in Mr. Lynch temporarily experiencing a Predator-like urge for revenge. The interesting thing about this particular song is the emphasis that Stephen puts on his urge to kill Bob. It’s interesting in that it doesn’t make much sense, morally speaking: it’s not as if Bob, a third party who was not involved in any kind of relationship with Stephen, had any formal obligation to respect the boundaries of Stephen’s relationship with his wife. Looking out for the relationship, it seems, ought to have been his wife’s job. She was the person who had the social obligation to Stephen that was violated, so it seems the one who Stephen ought to mad at (or, at least madder at) would be his wife. So why does Stephen wish to especially punish Bob?

“I swear I’ll get you Bob, even if it’s the last thing I do!”

There are two candidate explanations I’d like to consider today to help explain the urge for this kind of Bob-specific punishment: one is slightly more specific to the situation at hand and the other applies to punishment interactions more generally, so let’s start off with the more specific case. Stephen wants his wife to behave cooperatively in terms of their relationship, and she seems less than willing to do so herself; presumably, some mating mechanisms in her brain is suggesting that the payoffs would be better for her to ditch her jobless husband to run off with a wealthy, high-status doctor. In order to alter the cost/benefit ratio to certain actions, then, Stephen entertains the idea of enacting punishment. If Stephen’s punishment makes his wife’s infidelity costlier than remaining faithful, her behavior will likely adjust accordingly. While punishing his wife can potentially be an effective strategy for enforcing her cooperation, it’s also a risky venture for Stephen on two fronts: (1) too much punishing of his wife – in this case, murder, though it need not be that extreme – can be counterproductive to his goals, as it would render her less able to deliver the benefits she previously provided to the relationship; the punishment might also be counterproductive because (2) the punishment makes the relationship less valuable still to his wife as new costs mount, resulting in her urge to abandon the relationship altogether for a better deal elsewhere growing even stronger.

The punishing of potential third parties – in this case, Bob – does not hold these same costs, though. Provided Bob was a stranger, Stephen doesn’t suffer any loss of benefits, as benefits were never being provided by Bob in the first place. If Stephen and Bob were previously cooperating in some form the matter gets a bit more involved, but we won’t concern ourselves with that for now; we’ll just assume the benefits his wife could provide are more valuable than the ones Bob could. With regard to the second cost – the relationship becoming costlier for the person punishment is directed at – this is, in fact, not a cost when that punishment is directed at Bob, but rather the entire point. If the relationship is costlier for a third party to engage in, due to the prospect of a potentially-homicidal partner, that third party may well think twice before deciding whether to pursue the affair any further. Punishing Bob would seem to look like the better option, then. There’s just one major hitch: specifically, punishing is costly for Stephen, both in terms of time, energy, and risk, and he may well need to direct punishment towards far more targets if he’s attempting to prevent his wife from having sex with other people.

Punishing third parties versus punishing one’s partner can be thought of, by way of analogy, to treating the symptoms or the cause of a disease, respectively. Treating the symptoms (deterring other interested men), in this case, might be cheaper than treating the underlying cause on an individual basis, but you may also need to continuously treat the symptoms (if his wife is rather interested with the idea of having affairs more generally). Depending on the situation, then, it might be ultimately cheaper and more effective to treat either the cause or the symptoms of the problem. It’s probably safe to assume that the relative cost/benefit calculations being worked out cognitively might ultimately be represented to some degree in our desires: if some part of Stephen’s mind eventually comes to the conclusion, for whatever reasons, that punishing one or more third parties would be the cheaper of the two options, he might end up feeling especially interested in punishing Bob.

There is another, unexamined, set of costs, though, which brings us to the more general account. Stephen is not deciding whether to punish his wife and/or Bob in a social vacuum: what other people think about his punishment decisions will, in turn, likely effect Stephen’s perceptions of their attractiveness as options. If people are relatively lined up behind Stephen’s eventual decision, punishment suddenly becomes far less costly for Stephen to implement; by contrast, if others feel Stephen has gone to far and they align against him, his punishment would now become costlier and less effective (DeScioli & Kurzban, 2012). This brings us to a question I’ve raised before: would Stephen’s punishing of Bob result in the same social costs as the same punishment directed towards his wife? Strictly on the grounds that Bob is a man and Stephen’s wife is a woman, the answer to that question would seem to be “no”.

A paper by Glaeser and Sacerdote (2003) examined whether victim characteristics (like age and gender) were predictive of sentencing lengths for various crimes. The authors examined a sample of 1,772 cases in which manslaughter or murder charges were brought and a sentence was delivered, either due to a plea bargain or a conviction. Some of the expected racial bias seemed to raise its head, in that when the victim in question was black, the person sentenced for the killing was given less time (17.6 years, on average), overall, than when the victim was white (19.8 years). As was also the case in my last discussion of this topic, when the victim was a woman, sentence lengths were substantially shorter than when the victim was a man (17.5 vs 22.4 years, respectively). The difference is even starker when you consider the interaction between the gender of the person doing and kill and the gender of the person who got killed: when the victim was a man, if the killer was also a man, he would get about 18 years, on average; if the killer was a woman, that number drops to 11.3. For comparison’s sake, when the victim was a woman and the killer a woman, she would get about 17.5 years; if the killer was a man, that average was 23.1 years.

Those numbers, however, refer to all types of killings, so the sample was further restricted to vehicular homicides (about 7% of all homicides); essentially cases of people being killed by drunk drivers. These cases in particular are interesting because the victims here are, more or less, random; they just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and were not being targeted. Since these killings are relatively random, so to speak, the characteristics of the victim should be irrelevant to sentencing length, but they again were not. In these cases, if the person driving the car and doing the killing was a woman, she could expect a sentence of about 3 years for killing a man and 4.5 for killing another woman. If you replace the driver with a male, those numbers rise to 4.7 and 10.4 years respectively. Killing a woman netted a higher sentence in general, no matter your gender, but being a man doing the killing put you in an especially bad situation.

“Oh, good; we only hit a man. I was worried for a second there.”

So where does all that leave Stephen? If other people are more likely to align against Stephen for punishing his wife, relative to his punishing Bob, that, to some extent, makes the appeal of threatening or harming Bob seem (proportionally) all the sweeter. This analysis is not specifically targeted at gender (or race, or age), but at social value more generally. When deciding who to align with in these kinds of moral contexts, we should expect people to do so, in part, by cognitively computing (though not necessarily consciously) where their social investments will be most likely to yield a good return. Of course, determining the social value of others is not always easy task, as the variables which determine it will vary both in content and degree across people and across time. The larger point is simply that one’s social value can be determined not only by what you think of them, but by what others think of them as well. So even though Stephen’s wife was the only person cheating, Bob gets to be the party more likely to targeted for punishment, in no small part because of his gender.

References: Descioli, P. & Kurzban, R. (2012). A solution to the mysteries of morality. Psychological Bulletin, 1-20.

Glaeser, E., & Sacerdote, B. (2003). Sentencing in Homicide Cases and the Role of Vengeance The Journal of Legal Studies, 32 (2), 363-382 DOI: 10.1086/374707