Since my summer vacation is winding itself to a close, it’s time to relax with a fun, argumentative post that doesn’t deal directly with research. PZ Myers, an outspoken critic of evolutionary psychology – or at least an imaginary version of the field, which may bear little or no resemblance to the real thing – is back at it at again. After a recent defense of the field against PZ’s rather confused comments by Jerry Coyne and Steven Pinker, PZ has now responded to Pinker’s comments. Now, presumably, PZ feels like he did a pretty good job here. This is somewhat unfortunate, as PZ’s response basically plays by every rule outlined in the pop anti-evolutionary-psychology game: he asserts, incorrectly, what evolutionary psychology holds to as a discipline, fails to mention any examples of this going on in print (though he does reference blogs, so there’s that…), and then expressing wholehearted agreement with many of the actual theoretical commitments put forth by the field. So I wanted to take this time to briefly respond to PZ’s recent response and defend my field. This should be relatively easy, since it’s takes PZ a full two sentences into his response proper to say something incorrect.

Kicking off his reply, PZ has this to say about why he dislikes the methods of evolutionary psychology:

“PZ: That’s my primary objection, the habit of evolutionary psychologists of taking every property of human behavior, assuming that it is the result of selection, building scenarios for their evolution, and then testing them poorly.”

Familiar as I am with the theoretical commitments of the field, I find it strange that I overlooked the part that demands evolutionary psychologists assume that every property of human behavior is the result of selection. It might have been buried amidst all those comments about things like “byproducts”, “genetic drift”, “maladaptiveness” and “randomness” by the very people who, more or less, founded the field. Most every paper using the framework in the primary literature I’ve come across, strangely, seem to write things like “…the current data is consistent with the idea that [trait X] might have evolved to [solve problem Y], but more research is needed”, or might posit that,”…if [trait X] evolved to [solve problem Y], we. ought to expect [design feature Z]“. There is, however, a grain of truth to what PZ writes, and that is this: that hypotheses about adaptive function tend to make better predictions that non-adaptive ones. I highlighted this point in my last response to a post by PZ, but I’ll recreate the quote by Tooby and Cosmides here:

“Modern selectionist theories are used to generate rich and specific prior predictions about new design features and mechanisms that no one would have thought to look in the absence of these theories, which is why they appeal so strongly to the empirically minded….It is exactly this issue of predictive utility, and not “dogma”, that leads adaptationists to use selectionist theories more often than they do Gould’s favorites, such as drift and historical contingency. We are embarrassed to be forced, Gould-style, to state such a palpably obvious thing, but random walks and historical contingency do not, for the most part, make tight or useful prior predictions about the unknown design features of any single species.”

All of that seems to be besides the point, however, because PZ evidently doesn’t believe that we can actually test byproduct claims in the first place. You see, it’s not enough to just say that [trait X] is a byproduct; you need to specify what it’s a byproduct of. Male nipples, for instance, seem to be a byproduct of functional female nipples; female orgasm may be a byproduct of a functional male orgasm. Really, a byproduct claim is more a negative claim than anything else: it’s a claim that [trait X] has (or rather, had) no adaptive function. Substantiating that claim, however, requires one to be able to test for and rule out potential adaptive functions. Here’s what PZ had to say in his comments section about doing so:

“PZ: My argument is that most behaviors will NOT be the product of selection, but products of culture, or even when they have a biological basis, will be byproducts or neutral. Therefore you can’t use an adaptationist program as a first principle to determine their origins.”

Overlooking the peculiar contrasting of “culture” and “biological basis” for the moment, if one cannot use an adaptationist paradigm to test for possible functions in the first place, then it seems one would be hard-pressed to make any claim at all about function – whether that claim is that there is or isn’t one. One could, as PZ suggests, assume that all traits are non-functional until demonstrated otherwise, but, again, since we apparently cannot use an adaptationist analysis to determine function, this would leave us assuming things like “language is a byproduct”. This is somewhat at odds with PZ’s suggestion that “there is an evolved component of human language”, but since he doesn’t tell us how he reached that conclusion – presumably not through some kind of adaptationism program – I suppose we’ll all just have to live with the mystery.

Moving on, PZ raises the following question about modularity in the next section of his response:

“PZ: …why talk about “modules” at all, other than to reify an abstraction into something misleadingly concrete?”

Now this isn’t really a criticism about the field so much as a question about it, but that’s fine; questions are generally welcomed. In fact, I happen to think that PZ answers this question himself without any awareness of it, when he was previously discussing spleen function:

“PZ: What you can’t do is pick any particular property of the spleen and invent functions for it, which is what I mean by arbitrary and elaborate.”

While PZ is happy with the suggestion that spleen itself serves some adapted function, he overlooks the fact, and indeed, would probably take it for granted, that it’s meaningful to talk about the spleen as being a distinct part of the body in which it’s found. To put PZ’s comment in context, imagine some anti-evolutionary physiologist suggesting that it’s nonsensical to try and “pick any particular” part of the body and talk about “it’s specific function” as if it’s distinct from any other part (I imagine the exchange might go like this: “You’re telling me the upper half of the chest functions as a gas exchanger and the lower half functions to extract nutrients from food? What an arbitrary distinction!”). Of course, we know it does make sense to talk about different parts of the body – the heart, the lungs, and spleen – and we do so as each is viewed as having different functions. Modularity essentially does the same thing for the brain. Though the brain might outwardly appear to be a single organ, it is actually a collection of functionally-distinct pieces. The parts of your brain that process taste information aren’t good at solving other problems, like vision. Similarly, a system that processes sexual arousal might do terribly at generating language. This is why brain damage tends to cause rather-selective deficits in cognitive abilities, rather than global or unpredictable ones. We insist on modularity of the mind for the same reason PZ insists on modularity of the body.

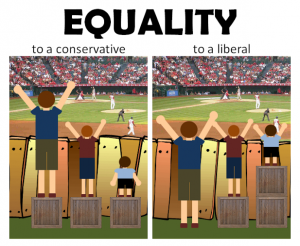

PZ also brings the classic trope of dichotomizing “learned/cultural” and “evolved/genetic” to bear, writing:

“PZ: …I suspect it’s most likely that they are seeing cultural variations, so trying to peg them to an adaptive explanation is an exercise in futility”

I will only give the fairly-standard reply to such sentiments, since they’ve been voiced so often before that it’s not worth spending much time on. Yes, cultures differ, and yes, culture clearly has effects on behavior and psychology. I don’t think any evolutionary psychologist would tell you differently. However, these cultural differences do not just come from nowhere, and neither do our consistent patterns of responses to those differences. If, for instance, local sex-ratios have some predictable effects on mating behavior, one needs to explain why that is the case. This is like the byproduct point above: it’s not enough to say “[trait X] is a product of culture” and leave it at that if you want an explanation of trait X that helps you understand anything about it. You need to explain why that particular bit of environmental input is having the effect that it does. Perhaps the effect is the result of psychological adaptation for processing that particular input, or perhaps the effect is a byproduct of mechanisms not designed to process it (which still requires identifying the responsible psychological adaptations), or perhaps the consistent effect is just a rather-unlikely run of random events all turning out the same. In any case, to reach any of these conclusions, one needs an adaptationist approach – or PZ’s magic 8-ball.

The final point I want to engage with are two rather interesting comments from PZ. The first comment comes from his initial reply to Coyne and the second from his reply to Pinker:

“PZ: I detest evolutionary psychology, not because I dislike the answers it gives, but on purely methodological and empirical grounds…Once again, my criticisms are being addressed by imagining motives”

While PZ continues to stress that, of course, he could not possibly have ulterior, conscious or unconscious, motives for rejecting evolutionary psychology, he then makes a rather strange comment in the comments section:

“PZ: Evolutionary psychology has a lot of baggage I disagree with, so no, I don’t agree with it. I agree with the broader principle that brains evolved.”

Now it’s hard to know precisely what PZ meant to imply with the word “baggage” there because, as usual, he’s rather light on the details. When I think of the word “baggage” in that context, however, my mind immediately goes to unpleasant social implications (as in, “I don’t identify as a feminist because the movement has too much baggage”). Such a conclusion would imply there are non-methodological concerns that PZ has about something related to evolutionary psychology. Then again, perhaps PZ simply meant some conceptual, theoretical baggage that can be remedied with some new methodology that evolutionary psychology currently lacks. Since I like to assume the best (you know me), I’ll be eagerly awaiting PZ’s helpful suggestions as to how the field can be improved by shedding its baggage as it moves into the future.