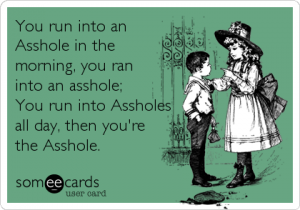

While I do my best to keep politics out of my life – usually by selectively blocking people who engage in too much proselytizing via link spamming on social media – I will never truly be rid of it. I do my best to cull my exposure to politics, not because I am lazy and looking to stay uninformed about the issues, but rather because I don’t particularly trust most of the sources of information I receive to leave me better informed than when I began. Putting this idea in a simple phrase, people are biased. In these socially-contentious domains, we tend to look for evidence that supports our favored conclusions first, and only stop to evaluate it later, if we do at all. If I can’t trust the conclusions of such pieces to be accurate, I would rather not waste my time with them at all, as I’m not looking to impress a particular partisan group with my agreeable beliefs. Naturally, since I find myself disinterested in politics – perhaps even going so far as to say I’m biased against such matters – this should mean I am more likely to approve of research that concludes people engaged with political issues aren’t quite good at reaching empirically-correct conclusions. Speaking of which…

“Holy coincidences, Batman; let’s hit them with some knowledge!”

A recent paper by Kahan et al (2013) examined how people’s political beliefs affected their ability to reach empirically-sound conclusions in the face of relevant evidence. Specifically, the authors were testing two competing theories for explaining why people tended to get certain issues wrong. The first of these is referred to as the Science Comprehension Thesis (SCT), which proposes that people tend to get different answers to questions like, “Is global warming affected by human behavior?” or “Are GMOs safe to eat?” simply because they lack sufficient education on such topics or possess poor reasoning skills. Put in more blunt terms, we might (and frequently do) say that people get the answers to such questions wrong because they’re stupid or ignorant. The competing theory the authors propose is called the Identity-Protective Cognition Thesis (ICT) which suggests that these debates are driven more by people’s desire to not be ostracized by their in-group, effectively shutting off their ability to reach accurate conclusions. Again, putting this in more blunt terms, we might (and I did) say that people get the answers to such questions wrong because they’re biased. They have a conclusion they want to support first, and evidence is only useful inasmuch as it helps them do that.

Before getting to the matter of politics, though, let’s first consider skin cream. Sometimes people develop unpleasant rashes on their skin and, when that happens, people will create a variety of creams and lotions designed to help heal the rash and remove its associated discomfort. However, we want to know if these treatments actually work; after all, some rashes will go away on their own, and some rashes might even get worse following the treatment. So we do what any good scientist does: we conduct an experiment. Some people will use the cream while others will not, and we track who gets better and who gets worse. Imagine, then, that you are faced with the following results from your research: of the people who did use the skin cream, 223 of them got better, while 75 got worse; of the people who did not use the cream, 107 got better, while 21 got worse. From this, can we conclude that the skin cream works?

A little bit of division tells us that, among those who used the cream, about 3 people got better for each 1 who got worse; among those not using the cream, roughly 5 people got better for each 1 who got worse. Comparing the two ratios, we can conclude that the skin cream is not effective; if anything, it’s having precisely the opposite result. If you haven’t guessed by now, this is precisely the problem that Kahan et al (2013) posed to 1,111 US adults (though they also flipped the numbers between the conditions so that sometimes the treatment was effective). As it turns out, this problem is by no means easy for a lot of people to solve: only about half the sample was able to reach the correct conclusion. As one might expect, though, the participant’s numeracy – their ability to use quantitative skills – did predict their ability to get the right answer: the highly-numerate participants got the answer right about 75% of the time; those in the low-to-moderate end of numeracy ability got it right only about 50% of the time.

“I need it for a rash. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it”

Kahan et al (2013) then switched up the story. Instead of participants reading about a skin cream, they instead read about gun legislation that banned citizens from carrying handguns concealed in public; instead of looking at whether a rash went away, they examined whether crime in the cities that enacted such bans went up or down, relative to those cities that did not. Beyond the change in variables, all the numbers remained exactly the same. Participants were asked whether the gun ban was effective at reducing crime. Again, people were not particularly good at solving this problem either – as we would expect – but an interesting result emerged: the most numerate subjects were now only solving the problem correctly 57% of the time, as compared with 75% in the skin-cream group. The change of topic seemed to make people’s ability to reason about these numbers quite a bit worse.

Breaking the data down by political affiliations made it clear what was going on. The more numerate subjects were, again, more likely to get the answer to the question correct, but only when it accorded with their political views. The most numerate liberal democrats, for instance, got the answer right when the data showed that concealed carry bans resulted in decreased crime; when crime increased, however, they were not appreciably better at reaching that conclusion relative to the less-numerate democrats. This pattern was reversed in the case of conservative republicans: when the concealed carry bans resulted in increased crime, the more numerate ones got the question right more often; when the ban resulted in decreased crime, performance plummeted.

More interestingly still, the gap in performance was greatest for the more-numerate subjects. The average difference in getting the right answer among the highly-numerate individuals was about 45% between cases in which the conclusion of the experiment did or did not support their view, while it was only 20% in the case of the less-numerate ones. Worth noting is that these differences did not appear when people were thinking about the non-partisan skin-cream issue. In essence, smart people were either not using their numeracy skills regularly in cases where it meant drawing unpalatable political conclusions, or they were using them and subsequently discarding the “bad” results. This is an empirical validation of my complaints about people ignoring base rates when discussing Islamic terrorism. Highly-intelligent people will often get the answers to these questions wrong because of their partisan biases, not because of their lack of education. They ought to know better – indeed, they do know better – but that knowledge isn’t doing them much good when it comes to being right in cases where that means alienating members of their social group.

That future generations will appreciate your accuracy is only a cold comfort

At the risk of repeating this point, numeracy seemed to increase political polarization, not make it better. These abilities are being used more to metaphorically high-five in-group members than to be accurate. Kahan et al (2013) try to explain this effect in two ways, one of which I think is more plausible than the other. On the implausible front, the authors suggest that using these numeracy abilities is a taxing, high-effort activity that people try to avoid whenever possible. As such, people with this numeracy ability only engage in effortful reasoning when their initial beliefs were threatened by some portion of the data. I find this idea strange because I don’t think that – metabolically – these kinds of tasks are particularly costly or effortful. On the more plausible front, Kahan et al (2013) suggest that these conclusions have a certain kind of rationality behind them: if drawing an unpalatable conclusion would alienate important social relations that one depends on for their own well-being, then an immediate cost/benefit analysis can favor being wrong. If you are wrong about whether GMOs are harmful, the immediate effects on you are likely quite small (unless you’re starving); on the other hand, if your opinion about them puts off your friends, the immediate social effects are quite large.

In other words, I think people sometimes interpret data in incorrect ways to suit their social goals, but I don’t think they avoid interpreting it properly because doing so is difficult.

References: Kahan, D., Peters, E., Dawson, E., & Slovic, P. (2013). Motivated numeracy and enlightened self-government. Yale Law School, Public Law Working Paper No. 307.