As part of my recent reading for an upcoming research project, I’ve been poking around some of the literature on cooperation and punishment, specifically second- vs. third-party punishment. Let’s say you have three people: A, B, and X. Person A and B are in a classic Prisoner’s Dilemma; they can each opt to either cooperate or defect and receive payments according to their decisions. In the case of second-party punishment, person A or B can give up some of their payment to reduce the other player’s payment after the choices have been made. For instance, once the game was run, person A could then give up points, with each point they give up reducing the payment of B by 3 points. This is akin to someone flirting with your boyfriend or girlfriend and you then blowing up the offender’s car; sure, it cost you a little cash for the gas, bottle, rag, and lighter, but the losses suffered by the other party are far greater.

Not only does it serve them right, but it’s also a more romantic gesture than flowers.

Not only does it serve them right, but it’s also a more romantic gesture than flowers.

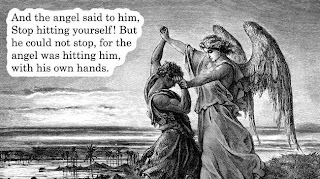

Third-party punishment involves another person, X, who observes the interaction between A and B. While X is unaffected by the outcome of the interaction itself, they are then given the option to give up some payment of their own to reduce the payment of A or B. Essentially, person X would be Batman swinging in to deliver some street justice, even if X’s parents may not have been murdered in front of their eyes.

Classic economic rationality would predict that no one should ever give up any of their payment to punish another player if the game is a one-shot deal. Paying to punish other players would only ensure that the punisher walks away with less money than they would otherwise have. Of course, we do see punishment in these games from both second- and third-parties when the option is available (though second-parties punish far more than third-parties). The reasons second-party punishment evolved don’t appear terribly mysterious: games like these are rarely one-shot deals in real life, and punishment sends a clear signal that one is not to be shortchanged, encouraging future cooperation and avoiding future losses. The benefits to this in the long-term can overcome the short-term cost of the punishment, for if person A knows person B is unable or unwilling to punish transgressions, person A would be able to continuously take advantage of B. If I know that you won’t waste your time pursuing me for burning your car down – since it won’t bring your car back – there’s nothing to dissuade me from burning it a second or tenth time.

Third-party punishment poses a bit more of a puzzle, which brings us to a paper by Fehr and Fischbacher (2004), who appear to be arguing in favor of group selection (at the very least, they don’t seem to find the idea implausible, despite it being just that). Since third-parties aren’t affected by the behavior of the others directly, there’s less of a reason to get involved. Being Batman might seem glamorous, but I doubt many people would be willing to invest that much time and money – while incurring huge risks to their own life – to anonymously deliver a benefit to a stranger. One of the possible ways third-party punishment could have benefited the punisher, as the authors note, is through reputational benefits: person X punishes person A for behaving unfairly, signaling to others that X is a cooperator and a friend – who also shouldn’t be trifled with – and that kindness would be reciprocated in turn. In an attempt to control for these factors, Fehr and Fischbacer ran some one-shot economic games where all players were anonymous and there was no possibility of reciprocation. The authors seemed to imply that any punishment in these anonymous cases is ultimately driven by something other than reputational self-interest.

“We just had everyone wear one of these. Problem solved”

“We just had everyone wear one of these. Problem solved”

The real question is do playing these games in an anonymous, one-shot fashion actually control for these factors or remove them from consideration? I doubt that they fully do, and here’s an example why: Alexander and Fisher (2003) surveyed men and women about their sexual history in anonymous and (potentially) non-anonymous conditions. Men reported an average of 3.7 partners in the non-anonymous condition and 4.2 in the anonymous one; women reported averages of 2.6 and 3.4 respectively. So there’s some evidence that the anonymous conditions do help.

However, there was also a third condition where the participants were hooked up to a fake lie detector machine – though ‘real’ lie detector machines don’t actually detect lies – and here the numbers (for women) changed again: 4 for men, 4.4 for women. While men’s answers weren’t particularly different across the three conditions, women’s number of sexual partners rose from 2.6 to 3.4 to 4.4. This difference may not have reached statistical significance, but the pattern is unmistakable.

On paper, she assured us that she found him sexy, and said her decision had nothing to do with his money. Good enough for me.

On paper, she assured us that she found him sexy, and said her decision had nothing to do with his money. Good enough for me.

What I’m getting at is that it should not just be taken for granted that telling someone they’re in an anonymous condition automatically makes people’s psychology behave as if no one is watching, nor does it suggest that moral sentiments could have arisen via group selection (it’s my intuition that truly anonymous one-shot conditions in our evolutionary history were probably rarely encountered, especially as far as punishment was concerned). Consider a few other examples: people don’t enjoy eating fudge in the shape of dog shit, drinking juice that has been in contact with a sterilized cockroach, holding rubber vomit in their mouth, eating soup from a never-used bedpan, or using sugar from a glass labeled “cyanide”, even if they labeled it themselves (Rozin, Millman, & Nemeroff 1986). Even though these people “know” that there’s no real reason to be disgusted by rubber, metal, fudge, or a label, their psychology still (partly) functions as if there was one.

I’ll leave you with one final example of how explicitly “knowing” something (i.e. this survey is anonymous; the sugar really isn’t cyanide) can alter the functioning of your psychology in some cases, to some degree, but not in all cases.

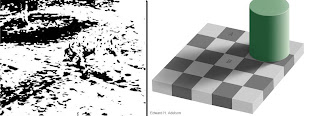

If I tell you you’re supposed to see a dalmatian in the left-hand picture, you’ll quickly see it and never be able to look at that picture again without automatically seeing the dog. If I told you that the squares labeled A and B are actually the same color in the right-hand picture, you’d probably not believe me at first. Then, when you cover up all of that picture except A and B and find out that they actually are the same color you’ll realize why people mistake me for Chris Angel from time to time.Also, when you are looking at the whole picture, you’ll never be able to see A and B as the same color, because that explicit knowledge doesn’t always filter down into other perceptual systems.

References: Alexander, M.G. & Fisher, T.D. (2003). Truth and consequences. Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self-reported sexuality. The Journal of Sex Research, 40, 27-35

Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. (2004). Third-party punishment and social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25, 63-87

Rozin, P., Millman, L., & Nemeroff, C. (1986). Operation of the laws of sympathetic magic in disgust and other domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 703-712

“Oh yeah; that’s it. You like cuddling, you whore. You love your satisfying and loving relationship, don’t you, you dirty girl?”