While we rely on our senses to navigate through life, there are certain quirks about the way our perception works that we often aren’t consciously aware of. It’s only when we encounter illusions, the most well-known of which tend to inhabit the visual domain, that certain inner workings of our perception modules become apparent. Take the following example as a good for instance: the checkerboard illusion. Given the proper context, our visual system is capable perceiving the two squares to be different colors despite the fact that they are the same color. On top of bringing certain facets of our visual modules into stark relief, the illusion demonstrates one other very important fact about our cognition: accuracy need not always be the goal. Our visual systems were only selected to be as good as they needed to be in order for us to do useful things, given the environment we tended to find ourselves in; they were not selected to be perfectly accurate in each and every situation they might find themselves in.

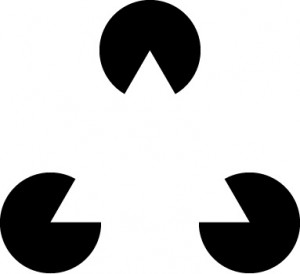

That endearing little figure is known as Kanizsa’s Triangle. While there is no actual triangle in the figure, some cognitive template is being automatically filled in given inputs from certain modules (probably ones designed for detecting edges and contrast), and the end result is that illusory perception; our mind automatically completes the picture, so to speak. This kind of automatic completion can have its uses, like allowing inferences to be drawn from a limited amount of information relatively quickly. Without such cognitive templates, tasks like learning language – or not walking into things – would be far more difficult, if not downright impossible. While picking up on recurrent and useful patterns of information in the world might lead to a perceptual quirk here and there, especially in highly abnormal and contrived scenarios like the previous two illusions, the occasional misfire is worth the associated gains.

Now let’s suppose that instead of detecting edges and contrasts we’re talking about detecting intentions and harm – the realm of morality. Might there be some input conditions that (to some extent) automatically result in a cognitive moral template being completed? Perhaps the most notable case came from Knobe (2003):

The vice president of a company went to the chairman of the board and said, “We are thinking of starting a new program. It will help us increase profits and it will also harm the environment.” The chairman of the board answered, “I don’t care at all about harming the environment, I just want to make as much profit as I can. Let’s start the new program.” They started the new program. Sure enough, the environment was harmed.

When asked, in this case most people suggested that the negative outcome was brought about intentionally and the chairman should be punished. When the word “harm” is replaced by help, people’s answers reverse and they now say the chairman wasn’t helping intentionally and deserves no praise.

Further research on the subject by Guglielmo & Malle (2010) found that the “I don’t care at all about…” in the preceding paragraph was indeed viewed differently by people depending on whether or not the person who said it was conforming to or violating a norm. When violating a norm, people tended to perceive some desire for that outcome in the violator, despite the violator stating they don’t care one way or the other; when conforming to a norm, people didn’t perceive that same desire given the same statement of indifference. The violation of a norm, then, might be used as part of an input for automatically filling in some moral template concerning perceptions of the violator’s desires, much like the Kanizsa Triangle. It can cause people to perceive a desire, even if there is none. This finding is very similar to another input condition I recently touched on: the perception of a person’s desires on their blameworthiness contingent on their ability to benefit from others being harmed (even if the person in question didn’t directly or indirectly cause the harm).

A recent paper by Grey et al (PDF here) builds upon this analogy rather explicitly. In it, they point out two important things: first, any moral judgment requires there be a victim and a perpetrator dyad; this represents the basic cognitive template of moral interactions through which all moral judgments can be understood. Second, the authors note that there need not actually be a real perpetrator or a victim for a moral judgment to take place; all that’s required is the perception of this pair.

Let’s return briefly to vision: when it comes to seeing the physical world, it’s better to have an accurate picture of it. This is because you can’t do things like persuade a cliff it’s not actually a cliff, or tell gravity to not pull you down. Thankfully, since the physical environment isn’t trying to persuade us of anything in particular either, accurate pictures of the world are relatively easy to come by. The social world, however, is full of agents that might be (and thus, probably are) misrepresenting information for their own benefit.

Taken together with the work just reviewed, this suggests that the moral template can be automatically completed: people can be led to either perceive victims or perpetrators where there are none (given they already perceive one or the other), or fail perceive victims and perpetrators that actually exist (given that they fail to perceive one or the other). Since accuracy isn’t the goal of these perceptions per se, whether the inputs given to the moral template are erased or cause it to be filled in will likely depend on their context; that is to say people should strategically “see” or “fail to see” victims or perpetrators, quite unlike whether people see the Kanizsa Triangle (they almost universally do). Some of possible reasons why people might fall in one direction or the other will be the topic of the next post.

References: Guglielmo, S., & Malle, B.F. (2010). Can Unintended Side Effects Be Intentional? Resolving a Controversy Over Intentionality and Morality Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin DOI: 10.1177/0146167210386733

Knobe, J. (2003). Intentional Action and Side Effects in Ordinary Language Analysis DOI: 10.1093/analys/63.3.190