I recently found myself engaged in an interesting discussion on the matter of abortion (everyone’s favorite topic for making friends and civil conversation). The unique thing about this debate was that I found myself in agreement with the other party when it came to the heart of the matter: whether abortions should be legally available and morally condemned (our answers would be “yes” and “no”, respectively). With such convergent views, one might wonder what there is left to argue about. Well, the discussion centered on whether I, as a man, should be able to have any opinion about abortion (positive or negative), or whether such opinions – and corresponding legislation – should be restricted to women. In this case, my friend suggested that I was, in fact, not entitled to hold any views about abortion because of my gender, going on to state that she was not interested in hearing any men’s opinions on the issue. She even went as far as to suggest that the feelings of a woman who disagreed with her stance about abortion would be more valid than mine on the matter. This struck me as a frankly sexist and bigoted view (in case you don’t understand why it sounds that way, imagine I ended this post by saying “I’m not interested in hearing any women’s views on this subject” and you should get the picture), but one I think is worth examining a bit further, especially because my friend’s view was not some anomaly; it’s a perspective I’ve heard before.

So it’s worth having my thoughts ready for future reference when this comes up again

As for the disagreement itself, I was curious why my friend felt this way: specifically, why she did she believe men are precluded from having opinions on abortions? Her argument was that men cannot understand the issue because they are not the one carrying the babies, having periods, taking hormonal birth control, feeling the day-to-day effects of pregnancy on one’s body, and so on. The argument, then, seems to involve the idea that women have privileged access to some relevant information (based on firsthand experience, or at least the potential of it) which men do not, as well as the idea that women are the ones enduring the lion’s share of the consequences resulting from pregnancy. I wanted to examine each of these claims to show why they do not yield the conclusion she felt they did.

The first piece of information I wanted to discuss is one I mentioned sometime ago: men and women do not appear to differ appreciably in their views regarding abortion. According to some Gallup data from 1975-2009 concerning the matter, between 22-35% of women believed abortion should be legal in all circumstance, 15-21% believed it should be illegal in all, and 48-55% of women believed it should be legal in some circumstances; the corresponding ranges for men were 21-29%, 13-19%, and 54-59%, respectively. From those numbers, we can see that men and women seem to hold largely similar views about abortion. My friend expressed a disinterest in hearing about this information, presumably because she did not feel it had any relevance to the argument at hand.

However, I feel there is a real relevance to those numbers that speaks to the first point my friend made: that women have privileged access to certain experiences and information men do not. It’s true enough that men and women have different experiences and perceptions in certain domains on average; I don’t know anyone who would deny that. However, those differences in experiences do not appear to yield substantial differences in opinion on the matter of abortion. This is a rather curious point. How are we to interpret this lack of a difference? Here are two ways that come to mind: first, we could continue to say that women have access to some privileged source of information bearing on the moral acceptability of abortion which men do not, but, despite this asymmetry in information, both sexes come to agreement about the topic in almost equal numbers anyway. In this case, then, we would be using a variable factor to explain a lack of differences between the sexes (i.e., “men and women come to agree on abortion almost perfectly owing to their vastly different experiences that the other sex cannot understand).

There might also just be a very similar person behind the mirror

This first interpretation strikes me as particularly unlikely, though not impossible. The second (and more likely) interpretation that comes to mind is that, despite frequent contentions to the contrary, variables relating to one’s sex per se – such as having periods or being the ones to give birth – are not actually the factors primarily driving views on abortion. If abortion views are driven instead by, say, one’s sexual strategy (whether one tends to prefer more long-term, monogamous or short-term, promiscuous mating arrangements), then the idea that men cannot understand arguments for or against abortion because of some unique experiences they do not have falls apart. Men and women both possess cognitive adaptions for long- and short-term mating strategies so, if those mechanisms are among the primary drivers of abortion views, the issue seems perfectly understandable for both sexes. Indeed, I haven’t heard an argument for or against abortion that has just left me baffled, as if it were spoken in a foreign language, regardless of whether I agree or not with it. Maybe I’m just not hanging out at the right parties and not hearing the right arguments.

Even if women were privy to some experiences which men could not understand and those unique experiences shaped their views on abortion, that still strikes me as a strange reason to disallow men from having opinions about it. Being affected by an issue in some unique way – or even primarily – does not mean you’re the only one affected by it, nor that other people can’t hold opinions about how you behave. One example I would raise to help highlight that point would be a fictional man I’ll call Tom. Tom happens to be prone to random outbursts of anger during which he has a habit of yelling at and fighting other people. I would not relate to Tom well; he is uniquely affected by something I am not and he likely sees the world much differently than I would. However, social species that we happen to be, his behavior resulting from those unique experiences has impacts on other people, allowing the construction of moral arguments for why he should or should not be condemned for doing what he does.

To say that abortion is a woman’s issue, or that they’re the only ones allowed to have opinions about it because they bear most of the consequences, is to overlook a lot of social impact. Men have mothers, sisters, friends, and sexual partners would who be affected by the legality of abortion; some men who do not wish to become fathers are certainly affected by abortion laws, just as men who wish to become fathers might be. To again turn to an analogy, one could try to make the argument that members of the military are the people most affected by the decision to go to war (they’re the ones who will be fighting and dying), so they should be the only one’s allowed to vote on the matter of whether our country enters armed combat. Objections to this argument might include propositions such as, “but civilians will be impacted by the war too” which, well, is kind of the whole point.

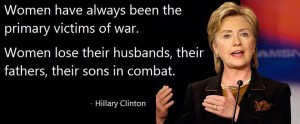

For example, see this rather strange quote

While one is free to hold to a particular political position without any reason beyond “that’s how I feel”, a position that ends up focusing on the sex of a speaker instead of their ideas seems like the kind of argument that socially-progressive individuals would want to avoid and fight against. To be clear, I’m not saying that sex is never relevant when it comes to determining one’s political and moral views: in my last post, for instance, I discussed the wide gap that appears between men and women with respect to their views about legalized prostitution, with men largely favoring it and women more often opposing it; a gap which widens when presented with information about how legalized prostitution is safer. What’s important to note in that case is that when sex is a relevant factor in the decision-making process we see differences in opinion between men and women’s views; not similarities. Those differences don’t imply that one sex’s average opinion is correct, mind you, but they serve as a cue that factors related to sex – such as mating interests – might be pulling some strings. In such cases, men and women might literally have a hard time understanding the opinion of the opposite sex, just as some people have trouble seeing the infamous dress as either black and blue or gold and white. That just doesn’t seem to be the case for abortion.

The same person who claims that only women are allowed to have an opinion on abortion because it’s a matter that is exclusive to women would also be the same person who would say that men aren’t allowed to have an opinion on cuckoldry* (*using the definition of forcing a man to provide for a child against his will or without his consent)/financial abortion of men even though that’s a matter exclusive to men.

http://www.salon.com/2000/10/19/mens_choice/

This suggests to me that such a persons’ arguments and beliefs are really about just shoring up that person’s power.

Once, while talking to a male friend who is more pro-choice than I am about abortion, he said, “I’m a man. I can’t even imagine what it would be like to be raped.”

But, of course, I had never been raped either. I have never even been in a situation where I feared rape. My friend seemed to think that rape was something women just sort of own, as condition of womanhood.

Similarly, I have never been pregnant. I have never worried about getting pregnant. I have never used birth control. Does my opinion on abortion still count? If so, than the validity of opinion doesn’t have anything to with experiences–it’s simple, straightforward sexism. If my opinion does *not* count, than the opinions of women who are less likely to support abortion (long-term maters, as you term it) are shut out of the discussion, which isn’t really how discussion (or laws) should work.