It’s a classic saying: The pen is mightier than the sword. While this saying communicates some valuable information, it needs to be qualified in a significant way to be true. Specifically, in a one-on-one fight, the metaphorical pens do not beat swords. Indeed, as another classic saying goes: Don’t bring a knife to a gun fight. If knives aren’t advisable against guns, then pens are probably even less advisable. This raises the question as to how – and why – pens can triumph over swords in conflicts. These questions are particularly relevant, given some recent happenings in California at Berkeley where a protest against a speaking engagement by Milo Yiannopoulos took a turn for the violent. While those who initiated the violence might not have been students of the school, and while many people who were protesting might not engage in such violence themselves when the opportunity arises, there does appear to be a sentiment among some people who dislike Milo (like those leaving comments over on the Huffington Post piece) that such violence is to be expected, is understandable, and sometimes even morally justified or praiseworthy. The Berkeley riot was not the only such incident lately, either.

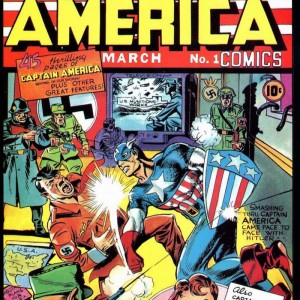

The Nazis shooting guns is a very important detail here

So let’s discuss why such violent behavior is often counterproductive for the swords in achieving their goals. Non-violent political movements, like those associated with leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi, appear to yield results, at least according to the only bit of data on the matter I’ve come across (for the link-shy: nonviolent campaigns combined complete and partial success rate was about 73%, while the comparable violent rate was about 33%). I even came across a documentary recently I intend to watch about a black man who purportedly got over 200 members of the KKK to leave the organization without force or the threat of it; he simply talked to them. That these nonviolent methods work at all seems rather unusual, at least if you were to frame it in terms of any other nonhuman species. Imagine, for instance, that a chimpanzee doesn’t like how he is being treated by the resident dominant male (who is physically aggressive), and so attempts to dissuade that individual from his behavior by nonviolently confronting him. No matter how many times the dominant male struck him, the protesting chimp would remain steadfastly nonviolent until he won over the other chimps in his group, and they all turned against the dominant male (or until the dominant male saw the error of his ways). As this would likely not work out for our nonviolent chimp, hopefully nonviolent protests are sounding a little stranger to you now; yet they often seem to work better than violence, at least for humans. We want to know why.

The answer to that question involves turning our attention back to the foundation of our moral sense: why do we perceive a dimension of right and wrong in the world in the first place? The short answer to this question, I think, is that when a dispute arises, those involved in the dispute find themselves in a state of transient need for social support (since numbers can decide the outcome of the conflict). Third parties (those not initially involved in the dispute) can increase their value as a social asset to one of the disputants by filling that need and assisting them in the fight against the rival. This allows third parties to leverage the transient needs of the disputants to build future alliances or defend existing allies. However, not all behaviors generate the same degree of need: the theft of $10 generates less need than a physical assault. Accordingly, our moral psychology represents a cognitive mechanism for determining what degree of need tends to be generated by behaviors in the interests of guiding where one’s support can best be invested (you can find the longer answer here). That’s not to say our moral sense will be the only input for deciding what side we eventually take – factors like kinship and interaction history matter too – but it’s an important part of the decision.

The applications of this idea to nonviolent protest ought to be fairly apparent: when property is destroyed, people are attacked, and the ability of regular citizens to go about their lives is disrupted by violent protests, this generates a need for social support on the part of those targeted or affected by the violence. It also generates worries in those who feel they might be targeted by similar groups in the future. So, while the protesters might be rioting because they feel they have important needs that aren’t being met (seeking to achieve them via violence, or the threat of it), third parties might come to view the damage inflicted by the protest as being more important or harmful (as they generate a larger, or more legitimate need). The net result of that violence is now that third parties side against the protesters, rather than with them. By contrast, a nonviolent protest does not create as large a need on the part of those it targets; it doesn’t destroy property or harm people. If the protesters have needs they want to see met and they aren’t inflicting costs on others, this can yield more support for the protester’s side.

I’m sure the owner of that car really had this coming…

This brings us to our third classic saying of the post: While I disagree with what you have to say, I will defend to the death your right to say it. Though such a sentiment might be seldom expressed these days, it highlights another important point: even if third parties agree with the grievances of the protesters (or, in this case, disagree with the behavior of the people being protested), the protesters can make themselves seem like suitably poor social assets by inflicting inappropriately-large costs (as disagreeing with someone generates less harm than stifling their speech through violence). Violence can alienate existing social support (since they don’t want to have to defend you from future revenge, as people who pick fights tend to initiate and perpetuate conflicts, rather than end them) and make enemies of allies (as the opposition now offers a better target of social investment, given their relative need). The answer as to why pens can beat swords, then, is not that pens are actually mightier (i.e., capable of inflicting greater costs), but rather that pens tend to be better at recruiting other swords to do their fighting for them (or, in more mild cases, pens can remove the social support from the swords, making them less dangerous). The pen doesn’t actually beat the sword; it’s the two or more swords the pen has persuaded to fight for it – and not the opposing sword – that do.

Appreciating the power of social support helps bolster our understanding of other possible interactions between pens and swords. For instance, when groups are small, swords will likely tend to be more powerful than pens, as large numbers of third parties aren’t around to be persuaded. This is why our nonviolent chimp example didn’t work well: chimps don’t reliably join disputes as third parties on the basis of behavior the way humans do. Without that third-party support, non-violence will fail. The corollary point here is that pens might find themselves in a bit of a bind when it comes to confrontations with other pens. Put in plain terms: nonviolence is a useful rallying cry for drawing social support if the other side of the dispute is being violent. If both sides abstain from violence, however, nonviolence per se no longer persuades people. You can’t convince someone to join your side in a dispute by pointing out something your side shares with the other. This should result in the expectation that people will frequently over-represent the violence of the opposition, perhaps even fabricating it completely, in the interests of persuading others.

Yet another point that can be drawn from this analysis is that even “bad” ideas or groups (whether labeled as such because of moral or factual reasons) can recruit swords to their side if they are targeted by violence. Returning to the cases we began with – the riot at UC Berkeley and the incident where Richard Spencer got punched – if you hope to exterminate people who hold disagreeable views, then violence might seem like the answer. However, as we have seen, violence against others, even disagreeable others, who are not themselves behaving violently can rally support from third parties, as they might begin to worry that threats to free speech (or other important issues) are more harmful than the opinions and words we find disagreeable (again, hitting someone creates more need than talking does). On the other hand, if you hope to persuade people to join your side (or at least not join the opposition), you will need to engage with arguments and reasoning. Importantly, you need to treat those you hope to persuade as people and engage with the ideas and values they actually hold. If the goal in these disputes really is to make allies, you need to convince others that you have their best interests at heart. Calling those who disagree “baskets of deplorables,” suggesting they’re too stupid to understand the world, or anything to that extent doesn’t tend to win their hearts and minds. If anything, it sends a signal to them that you do not value them, giving them all the more reason to not spend their time helping you achieve your goals.

“Huh; I guess I really am a moron and you’re right. Well done,” said no one, ever.

As a final matter, we could also discuss the idea that violence is useful at snuffing out threats preemptively. In other words, better to stop someone before they can try and attack you, rather than after their knife is already in your back. There are several reasons preemptive defense is just as suspect, so let’s run through a few: first, there are different legal penalties for acts like murder and attempted murder, as attempted – but incomplete acts – generate less needs than completed ones. As such, they garner less social support. Second, absent very strong evidence that the people targeted for violence would have eventually become violent, the preemptive attacks will not look defensive; they will simply look aggressive, returning to the initial problems violent protests face. Relatedly, it is unlikely to ever make allies of enemies; if anything, it will make deeper enemies of existing ones and their allies. Remember: when you hurt someone, you indirectly inflict costs on their friends, families, and other relations as well. Finally, some people will likely develop reasonable concerns about the probability of being attacked for holding other opinions or engaging in behaviors people find unpleasant or dangerous. With speech already being equated to violence among certain groups, this concern doesn’t seem unfounded.

In the interests of persuading others – actors and third parties alike – nonviolence is usually the better first step. However, nonviolence alone is not enough, especially if your opposition is nonviolent as well. Not being violent does not mean you’ve already won the dispute; just that you haven’t lost it. It is at that point you need to persuade others that your needs are legitimate, your demands reasonable, and your position in their interests as well, all while your opposition attempts to be persuasive themselves. It’s not an easy task, to be sure, and it’s one many of us are worse at then we’d like to think; it’s just the best way forward.