If I had the power to reach inside your mind and effect your behavior, this would be quite the adaptive skill for me. Imagine being able to effortless make your direct competitors less effective than you, those who you find appealing more interested in associating with you, and, perhaps, even reaching inside your own mind, improving your performance to levels you couldn’t previously reach. While it would be good for me to possess these powers, it would be decidedly worse for other people if I did. Why? Simply put, because my adaptive best interests and theirs do not overlap 100%. Improving my standing in the evolutionary race will often come at their expense, and being able to manipulate them effectively would do just that. This means that they would be better off if they possessed the capacity to resist my fictitious mind-control powers. To bring this idea back down to reality, we could consider the relationship between parasites and hosts: parasites often make their living at their host’s expense, and the hosts, in turn, evolve defense mechanisms – like immune systems – to fight off the parasites.

Now with 10% more Autism!

This might seem rather straightforward: avoiding manipulative exploitation is a valuable skill. However, the same kind of magical thinking present in the former paragraph seems to present in psychological research from time to time; the line of reasoning that goes, “people have this ability to reach into the minds of others and change their behavior to suit their own ends”. Admittedly, the reasoning is a lot more subtle and requires some digging to pick up on, as very few psychologists would ever say that humans possess such magical powers (with Daryl Bem being one notable exception). Instead, the line of thinking seems to go something like this: if I hold certain beliefs about you, you will begin to conform to those beliefs; indeed, even if such beliefs exist in your culture more generally, you will bend your behavior to meet them. If I happen to believe you’re smart, for example, you will become smarter; if I happen to believe you are a warm, friendly person, you will become warmer. This, of course, is expected to work in the opposite direction as well: if I believe you’re stupid, you will subsequently get dumber; if I believe you’re hostile, you will in turn become more hostile. This is a bit of an oversimplification, perhaps, but it captures the heart of these ideas well.

The problem with this line of thinking is precisely the same as the problem I outlined initially: there is a less than perfect (often far less than perfect) overlap between the reproductive best interests of the believers and the targets. If I allowed your beliefs about me to influence my behavior, I could be pushed and pulled in all sorts of directions I would rather not go in. Those who would rather not see me succeed could believe that I will fail, which would, generally, have negative implications for my future prospects (unless, of course, other people could fight that belief by believing I would succeed, leading to an exciting psychic battle). It would be better for me if I ignored their beliefs and simply proceeded forward on my own. In light of that, it would be rather strange to expect that humans possess cognitive mechanisms which use the beliefs of others as inputs for deciding our own behavior in a conformist fashion. Not only are the beliefs of others hard to accurately assess directly, but conforming to them is not always a wise idea even if they’re inferred correctly.

This hasn’t stopped some psychologists from suggesting that we do basically that, however. One such line of research that I wanted to discuss today is known as “stereotype threat”. Pulling a quick definition from reducingstereotyethreat.org: “Stereotype threat refers to being at risk of confirming, as self-characteristic, a negative stereotype about one’s group”. From the numerous examples they list, a typically research paradigm involves some variant of the following: (1) get two groups together to take a test that (2) happen to differ with respect to cultural stereotypes about who will do well. Following that, you (3) make salient their group membership in some way. The expected result is that the group that is on the negative end of the stereotype will perform worse when they’re aware of their group membership. To turn that into an easy example, men are believed to be better at math than women, so if you remind women about their gender prior to a math test, they ought to do worse than women not so reminded. The stereotype of women doing poorly on math actually makes women perform worse.

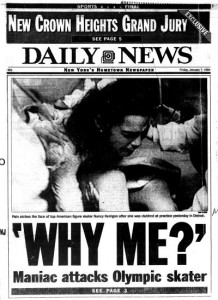

The psychological equivalent of getting Nancy Kerrigan’d

In the interests of understanding more about stereotype threat – specifically, its developmental trajectory with regard to how children of different ages might be vulnerable to it – Ganley et al (2013) ran three stereotype threat experiments with 931 male and female students, ranging from 4th to 12th grade. In their introduction, Ganley et al (2013) noted that some researchers regularly talk about the conditions under which stereotype threat is likely to have its negative impact: perhaps on hard questions, relative to easy ones; on math-identified girls but not non-identified ones; ones in mixed-sex groups but not single-sex groups, and so on. While some psychological phenomenon are indeed contextually specific, one could also view all that talk of the rather specific contexts required for stereotype threat to obtain as a post-hoc justification for some sketchy data analysis (didn’t find the result you wanted? Try breaking the data into different groups until you do find it). Nevertheless, Ganley et al (2013) set up their experiments with these ideas in mind, doing their best to find the effect: they selected high-performing boys and girls who scored above the mid-point of math identification, used evaluative testing scenarios, and used difficult math questions.

Ganley et al (2013) even used some rather explicit stereotype threat inductions: rather than just asking students to check off their gender (or not do so), their stereotype-threat conditions often outright told the participants who were about to take the test that boys outperform girls. It doesn’t get much more threatening than that. Their first study had 212 middle school students who were told either that boys showed more brain activation associated with math ability and, accordingly, performed better than girls, or that both sexes performed equally well. In this first experiment, there was no effect of condition: the girls who were told that boys do better on math tests did not under-perform, relative to the girls who were told that both sexes do equally well. In fact, the data went in the opposite direction, with girls in the stereotype threat condition performing slightly, though not significantly, better. Their next experiment had 224 seventh-graders and 117 eighth-graders. In this stereotype threat condition, they were asked to indicate their gender on a test before than began it because boys tended to outperform girls on these measures (this wasn’t mentioned in the control condition). Again, the results found no stereotype threat at either grade and, again, their data went in the opposite direction, with stereotype threat groups performing better.

Finally, their third study contained 68 forth-graders, 105 eighth-graders, and 145 twelfth-graders. In this stereotype threat condition, students first solved an easy math problem concerning many more boys being on the math team than girls before taking their test (the control condition’s problem did not contain the sex manipulation). They also tried to make the test seem more evaluative in the stereotype threat condition (referring to it as a “test”, rather than “some problems”). Yet again, no stereotype threat effects emerged at any grade level, with two of the three means going in the wrong direction. No matter how they sliced it, no stereotype threat effects fell out. Their data wasn’t even consistently in the direction of stereotype threat being a negative thing. Ganley et al (2013) even took their analysis just a little further in the discussion section, noting that published studies of such effects found some significant effect 80% of the time. However, these effects were also reported among other, non-significant findings. In other words, these effects were likely found after cutting the data up in different ways. By contrast, the three unpublished dissertations on stereotype threat all found nothing, suggesting the possibility that both data cheating and publication bias were probably at work in the literature (and they’re not the only ones).

”Gone fishing for P-values”

The current findings appear to build upon the trend of the frequently non-replicable nature of psychological research. More importantly, however, the type of thinking that inspired this research doesn’t seem to make much sense in the first place, though that part doesn’t seem to be discussed at all. There are good reasons to not let the beliefs of others affect your performance; an argument needs to made as to why we would be sensitive to such things, especially when they’re hypothesized to make us worse, and it isn’t present. To make that point crystal clear, try and apply stereotype threat thinking to any non-human species and see how plausible it sounds. By contrast, a real theory, like kin selection, applies with just as much force to humans as it does to other mammals, birds, insects, and even single-cell organisms. If there’s no solid (and plausible) adaptive reasoning in which one grounds their work – as there isn’t with stereotype threat – it should come as no surprise that effects flicker in and out of existence.

References: Ganley, C., Mingle, L., Ryan, A., Ryan, K., Vasilyeva, M., & Perry, M. (2013). An examination of stereotype threat effects on girls’ mathematical performance. Developmental Psychology, 49, 1886-1897.