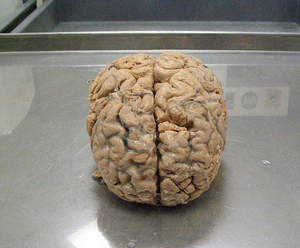

One lesson I always try to drive home in any psychology course I teach is that biology (and, by extension, psychology) is itself costly. The usual estimate on offer is that our brains consume about 20% of our daily caloric expenditure, despite making up a small portion of our bodily mass. That’s only the cost of running the brain, mind you; growing and developing it adds further metabolic costs into the mix. When you consider the extent of those costs over a lifetime, it becomes clear that – ideally – our psychology should only be expected to exist in an active state to the extent it offers adaptive benefits that tend to outweigh them. Importantly, we should also expect that cost/benefit analysis to be dynamic over time. If a component of our biology/psychology is useful during one point in our lives but not at another, we might predict that it would switch on or off accordingly. This line of thought could help explain why humans are prolific language learners early in life but struggle to learn a second language in their teens and beyond; a language-learning mechanism active during development it would be useful up to a certain age for learning a native tongue, but later becomes inactive when its services are no longer liable to required, so to speak (which they often wouldn’t be in an ancestral environment in which people didn’t travel far enough to encounter speakers of other languages).

“Good luck. Now get to walking!”

The two key points to take away from this idea, then, are (a) that biological systems tend to be costly and, because of that, (b) the amount of physiological investment in any one system should be doled out only to the extent it is likely to deliver adaptive benefits. With those two points as our theoretical framework, we can explain a lot about behavior in many different contexts. Consider mating as a for instance. Mating effort intended to attract and/or retain a partner is costly to engage in (in terms of time, resource invest, risk, and opportunity costs), so people should only be expected to put effort into the endeavor to the extent they view it as likely to produce benefits. As such, if you happen to be a hard “5″ on the mating market, it’s not worth your time pursuing a mate that’s a “9″ because you’re probably wasting your effort; similarly, you don’t want to pursue a “3″ if you can avoid it, because there are better options you might be able to achieve if you invest your efforts elsewhere.

Speaking of mating effort, this brings us to the research I wanted to discuss today. Sticking to mammals just for the sake of discussion, males of most species endure less obligate parenting costs than females. What this means is that if a copulation between a male and female results in conception, the female bears the brunt of the biological costs of reproduction. Many males will only provide some of the gametes required for reproduction, while the females must provide the egg, gestate the fetus, birth it, and nurse/care for it for some time. Because the required female investment is substantially larger, females tend to be more selective about which males they’re willing to mate with. That said, even though the male’s typical investment is far lower than the female’s, it’s still a metabolically-costly investment: the males need to generate the sperm and seminal fluid required for conception. Testicles need to be grown, resources need to be invested into sperm/semen production, and that fluid needs to be rationed out on a per-ejaculation basis (a drop may be too little, while a cup may be too much). Put simply, males cannot afford to just produce gallons of semen for fun; it should only be produced to the extent that the benefits outweigh the costs.

For this reason, you tend to see that male testicle size varies between species, contingent on the degree of sperm competition typically encountered. For those not familiar, sperm competition refers to the probability that a female will have sperm from more than one male in her reproductive tract at a time when she might conceive. In a concrete sense, this translates into a fertile female mating with two or more males during her fertile window. This creates a context that favors the evolution of greater male investment into sperm production mechanisms, as the more of your sperm are in the fertilization race, the greater your probability of beating the competition and reproducing. When sperm competition is rare (or absent), however, males need not invest as many resources into mechanisms for producing testes and they are, accordingly, smaller.

Find the sperm competition

This logic can be extended to matters other than sperm competition. Specifically, it can be applied to cases where a male is (metaphorically) deciding how much to invest into any given ejaculate, even if he’s the female’s only sexual partner. After all, if the female you’re mating with is unlikely to get pregnant at the time, whatever resources are being invested into an ejaculate are correspondingly more likely to represent wasted effort; a case where the male would be better off investing those resources to things other than his loins. What this means is that – in addition to between-species differences of average investment in sperm/semen production – there might also exist within-individual differences in the amount of resources devoted to a given ejaculate, contingent on the context. This idea falls under the lovely-sounding name, the theory of ejaculate economics. Put into a sentence, it is metabolically costly to “buy” ejaculates, so males shouldn’t be expected to invest in them irrespective of their adaptive value.

A prediction derived from this idea, then, is that males might invest more in semen quality when the opportunity to mate with a fertile female is presented, relative to when that same female is not as likely to conceive. This very prediction happens to have been recently examined by Jeannerat et al (2017). Their sample for this research consisted of 16 adult male horses and two adult females, each of which had been living in a single-sex barn. Over the course of seven weeks, the females were brought into a new building (one at a time) and the males were brought in to ostensibly mate with them (also one at a time). The males would be exposed to the female’s feces on the ground for 15 seconds (to potentially help them detect pheromones, we are told), after which the males and females were held about 2 meters from each other for 30 seconds. Finally, the males were led to a dummy they could mount (which had also been scented with the feces). The semen sample from that mount was then collected from the dummy and the dummy refreshed for the next male.

This experiment was repeated several times, such that each stallion eventually provided semen after exposure to each mare two or three times. The crucial manipulation, however, involved the mares: each male had provided a semen sample for each mare once when she was ovulating (estrous) and two to three times when she was not (dioestrous). These samples were then compared against each other, yielding a within-subjects analysis of semen quality.

The result suggested that the stallions could – to some degree – accurately detect the female’s ovulatory status: when exposed to estrous mares, the stallions were somewhat quicker to achieve erections, mount the dummy, and to ejaculate, demonstrating a consistent pattern of arousal. When the semen samples themselves were examined, another interesting set of patterns emerged: relative to dioestrous mares, when the stallions were exposed to estrous mares they left behind larger volumes of semen (43.6 mL vs 46.8 mL) and more motile sperm (a greater percentage of active, moving sperm; about 59 vs 66%). Moreover, after 48 hours, the sperm samples obtained from the stallions exposed to estrous mares showed less of a decline of viability (66% to 65%) relative to those obtained from dioestrous exposure (64% to 61%). The estrous sperm also showed reduced membrane degradation, relative to the dioestrous samples. By contrast, sperm count and velocity did not significantly differ between conditions.

“So what it was with a plastic collection pouch? I still had sex”

While these differences appear slight in the absolute sense, they are nevertheless fascinating as they suggest males were capable of (rather quickly) manipulating the quality of the ejaculate they provided from intercourse, depending on the fertility status of their mate. Again, this was a within-subjects design, meaning the males are being compared against themselves to help control for individual differences. The same male seemed to invest somewhat less in an ejaculate when the corresponding probability of successful fertilization was low.

Though there are many other questions to think about (such as whether males might also make long-term adjustments to semen characteristics depending on context, or what the presence of other males might do, to name a few), one that no doubt pops into the minds of people reading this is whether other species – namely, humans – do something similar. While it is certainly possible, from the present results we clearly cannot say; we’re not horses. An important point to note is that this ability to adjust semen properties depends (in part) on the male’s ability to accurately detect female fertility status. To the extent human males have access to reliable cues regarding fertility status (beyond obvious ones, like pregnancy or menstruation), it seems at least plausible that this might hold true for us as well. Certainly an interesting matter worth examining further.

References: Jeannerat, E., Janett, F., Sieme, H., Wedekind, C., & Burger, D. (2017). Quality of seminal fluids varies with type of stimulus at ejaculation. Scientific Reports. 7, DOI: 10.1038/srep44339