“It’s a basic truth of the human condition that everybody lies; the only variable is about what“

One of my favorite shows from years ago was House; a show centered around a brilliant but troubled doctor who frequently discovers the causes of his patient’s ailments through discerning what they – or others – are lying about. This outlook on people appears to be correct, at least in spirit. Because it is sometimes beneficial for us that other people are made to believe things that are false, communication is often less than honest. This dishonesty entails things like outright lies, lies by omission, or stretching the truth in various directions and placing it in different lights. Of course, people don’t just lie because deceiving others is usually beneficial. Deception – much like honesty – is only adaptive to the extent that people do reproductively-relevant things with it. Convincing your spouse that you had an affair when you didn’t is dishonest for sure, but probably not a very useful thing to do; deceiving someone about what you had for breakfast is probably fairly neutral (minus the costs you might incur from coming to be known as a liar). As such, we wouldn’t expect selection to have shaped our psychology to lie about all topics with equal frequency. Instead, we should expect that people tend to preferentially lie about particular topics in predictable ways.

Lies like, “This college degree will open so many doors for you in life”

The corollary idea to that point concerns skepticism. Distrusting the honesty of communications can protect against harmful deceptions, but it also runs the risk of failing to act on accurate and beneficial information. There are costs and benefits to skepticism as there are to deception. Just as we shouldn’t expect people to be dishonest about all topics equally often, then, we shouldn’t expect people to be equally skeptical of all the information they receive either. This is point I’ve talked about before with regards to our reasoning abilities, whereby information agreeable to our particular interests tends to be accepted less critically, while disagreeable information is scrutinized much more intensely.

This line of thought was recently applied to the mating domain in a paper by Walsh, Millar, & Westfall (2016). Humans face a number of challenges when it comes to attracting sexual partners typically centered around obtaining the highest quality of partner(s) one can (metaphorically) afford, relative to what one offers to others. What determines the quality of partners, however, is frequently context specific: what makes a good short-term partner might differ from what makes a good long-term partner and – critically, as far as the current research is concerned – the traits that make good male partners for women are not the same as those that make good females partner for men. Because women and men face some different adaptive challenges when it comes to mating, we should expect that they would also preferentially lie (or exaggerate) to the opposite sex about those traits that the other sex values the most. In turn, we should also expect that each sex is skeptical of different claims, as this skepticism should reflect the costs associated with making poor reproductive decisions on the basis of bad information.

In case that sounds too abstract, consider a simple example: women face a greater obligate cost when it comes to pregnancy than men do. As far as men are concerned, their role in reproduction could end at ejaculation (which it does, for many species). By contrast, women would be burdened with months of gestation (during which they cannot get pregnant again), as well as years of breastfeeding prior to modern advancements (during which they also usually can’t get pregnant). Each child could take years of a woman’s already limited reproductive lifespan, whereas the man has lost a few minutes. In order to ease those burdens, women often seek male partners who will stick around and invest in them and their children. Men who are willing to invest in children should thus prove to be more attractive long-term partners for women than those who are unwilling. However, a man’s willingness to stick around needs to be assessed by a woman in advance of knowing what his behavior will actually be. This might lead to men exaggerating or lie about their willingness to invest, so as to encourage women to mate with them. Women, in turn, should be preferentially skeptical of such claims, as being wrong about a man’s willingness to invest is costly indeed. The situation should be reversed for traits that men value in their partners more than women.

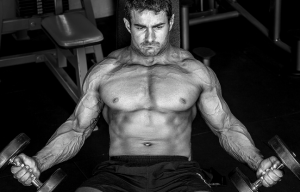

Figure 1: What men most often value in a woman

Three such traits for both men and women were examined by Walsh et al (2016). In their study, eight scenarios depicting a hypothetical email exchange between a man and woman who had never met were displayed to approximately 230 (mostly female; 165) heterosexual undergraduate students. For the women, these emails depicted a man messaging a woman; for men, it was a woman messaging a man. The purpose of these emails was described as the person sending them looking to begin a long-term intimate relationship with the recipient. Each of these emails described various facets of the sender, which could be broadly classified as either relevant primarily to female mating interests, relevant to male interests, or neutral. In terms of female interests, the sender described their luxurious lifestyle (cuing wealth), their desire to settle down (commitment), or how much they enjoy interacting with children (child investment). In terms of male interests, the sender talked about having a toned body (cuing physical attractiveness), their openness sexually (availability/receptivity), or their youth (fertility and mate value). In the two neutral scenarios, the sender either described their interest in stargazing or board games.

Finally, the participants were asked to rate (on a 1-5 scale) how deceitful they thought the sender was, whether they believed the sender or not, and how skeptical they were of the claims in the message. These three scores were summed for each participant to create a composite score of believability for each of the messages (the lower the score, the less believable it was rated as being). Those scores were then averaged across the female-relevant items (wealth, commitment, and childcare), the male-relevant items (attractiveness, youth, and availability), and the control conditions. (Participants also answered questions about whether the recipient should respond and how much they personally liked the sender. No statistical analyses are reported on those measures, however, so I’m going to assume nothing of note turned up)

The results showed that, as expected, the control items were believed more readily (M = 11.20) than the male (M = 9.85) or female (9.6) relevant items. This makes sense, inasmuch as believing lies about stargazing or interests in board games aren’t particularly costly for either sex in most cases, so there’s little reason to lie about them (and thus little reason to doubt them); by contrast, messages about one’s desirability as a partner have real payoffs, and so are treated more cautiously. However, an important interaction with the sex of the participant was uncovered as well: female participants were more skeptical on the female-relevant items (M = about 9.2) than males were (M = 10.6); similarly, males were more likely to be skeptical in male-relevant conditions (M = 9.5) than females were (M = 10). Further, the scores for the individual items all showed evidence of the same sex kinds of differences in skepticism. No sex difference emerged for the control condition, also as expected.

In sum, then – while these differences were relatively small in magnitude – men tended to be more skeptical of claims that, if falsely believed, were costlier for them than women, and women tended to be more skeptical of claims that, if falsely believed, were costlier for them than men. This is a similar pattern to that found in the reasoning domain, where evidence that agrees with one’s position is accepted more readily than evidence that disagrees with it.

“How could it possibly be true if it disagrees with my opinion?”

The authors make a very interesting point towards the end of their paper about how their results could be viewed as inconsistent with the hypothesis that men have a bias to over-perceived women’s sexual interest. After all, if men are over-perceiving such interest in the first place, why would they be skeptical about claims of sexual receptivity? It is possible, of course, that men tend to over-perceive such availability in general and are also skeptical of claims about its degree (e.g., they could still be manipulated by signals intentionally sent by females and so are skeptical, but still over-perceive ambiguous or less-overt cues), but another explanation jumps out at me that is consistent with the theme of this research: perhaps when asked to self-report about their own sexual interest, women aren’t being entirely accurate (consciously or otherwise). This explanation would fit well with the fact that men and women tend to perceive a similar level of sexual interest in other women. Then again, perhaps I only see that evidence as consistent because I don’t think men, as a group, should be expected to have such a bias, and that’s biasing my skepticism in turn.

References: Walsh, M., Millar, M., & Westfall, S. (2016). The effects of gender and cost on suspicion in initial courtship communications. Evolutionary Psychological Science, DOI 10.1007/s40806-016-0062-8